Rosa Mulholland, Digital Renaissance and Digital Humanities in Trier, Germany

Citation: Brassil, G. and K. Laing. (2025) ‘Rosa Mulholland, Digital Renaissance and Digital Humanities in Trier, Germany’, IWWN Blog, date of posted entry. Available at (accessed date)

Geraldine Brassil and Kathryn Laing

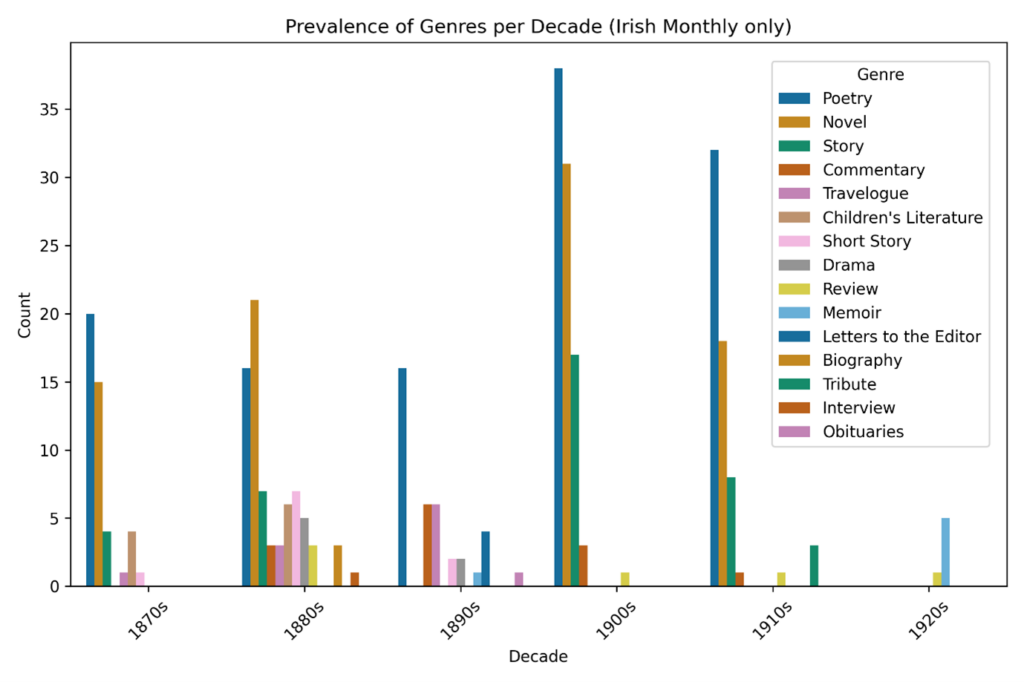

In March 1909 Rosa Mulholland’s short story, ‘Krescenz: An Idyll on the Moselle’, was published in the Irish Monthly, a literary magazine established and edited by the Jesuit Fr Matthew Russell in 1873.[1] Mulholland was a core author almost from its inception, and the story of Krescenz is one of at least 300 of her contributions to the Irish Monthly that included short stories, serialised stories, poems, dramas and a range of non-fiction. This bibliographical information is stored in a comprehensive dataset that we have created specifically for our Rosa Mulholland Project (see Figure 1).[2] Aligning with the aims and focus of the Irish Women’s Writing Network (1880-1920), the project includes the recovery, recording and mapping of Mulholland’s prolific publishing life, from the earliest identified publication in 1862 to the year of her death in 1921.[3] Building this resource by trawling through digitised and other archives remains a painstaking process.[4] How to organise a significant collection of cultural metadata already gathered from late nineteenth-century newspaper and magazine articles/essays/stories, for example, and making these visible and accessible for readers and scholars, is another challenge.

Rosa Mulholland (1841-1921)

Figure 1 Rosa Mulholland’s presence in the Irish Monthly from 1873-1921. A publication is counted as more than one if serialised or produced in parts over multiple issues of the Irish Monthly. Our thanks to Christof Schöch for producing this visualisation based on our metadata.

We were inspired by various much larger but aligned digital projects as we searched for ways in which we might meet these challenges.[5] The Computational Literary Studies Infrastructure (CLS INFRA) Fellowship Programme offered us the ideal opportunity to acquire new knowledge, skills and fluency in the digital methods necessary for us to develop a plan and a methodology critical for the advancement of our project.[6] And so, following a successful application, we found ourselves based in the Digital Humanities Department at Trier University, Germany in January 2025. The TCDH team are pioneering ‘digital architects’ in the field of Digital Humanities. They have ‘co-developed internationally recognized standards and methods for the digitization and archiving of digital data, created software for the transcription and collation of manuscripts, worked with humanities scholars on the application of their methods to textual data, developed concepts, digital tools and technologies and, thus, participated in numerous projects for the digital renaissance of poets, thinkers and cultural treasures’(https://tcdh.uni-trier.de/en/profile). Access to such expertise was undoubtably an invaluable learning opportunity for progressing our own project.

Work on the Rosa Mulholland dataset, in preparation for the two-week fellowship, uncovered a story set on the Moselle in turn-of-the-century Trier, an extraordinary city of Roman origins and a much later strong Catholic pilgrimage tradition. Here was a serendipitous turn, Mulholland’s late nineteenth-century tale providing a backdrop for two of her twenty-first century readers visiting the city and university, with a goal to learn how to capture and bring her work, and more broadly the writing of her Irish literary contemporaries, to a larger readership in the digital realm.[7]

Mulholland’s atmospheric but sad story of a young woman betrayed in love is set on the banks of the Moselle. The story begins by describing an

‘evening in the ancient town of Trier; the Angelus was ringing down from the great fortress-like Dom; the little carts and stalls had vanished out of the market-place; and the carved saints, clustered on the fountain, smiled benignly in the setting sun. Old women, in strange head-dresses, beads and books in hand, passed in and out of St. Gondolphus’s curious gates; young girls, with long, fair, plaited hair, moved in groups across the open Place; brilliant uniforms shone upon the balconies of the Rothe Haus; the shopkeepers in the queer little peaked houses stood at their doors and amused themselves; while the awful black arches of the Porta Nigra frowned more grimly than ever in the glowing light, and the gay and quaint little frescoes at the street corners seemed to blaze out with new colour at its touch’ (1909, p. 121).

St Peter’s Cathedral

St Gandolf’s Church

‘the awful black arches of the Porta Nigra’ & Karl Marx (1818-1883), Trier

Krescenz is an impoverished seamstress who lives in these streets in a bare house with a high peaked roof. She has cared for her brother Max since he was one day old. When Max brings the news that Karl, Krescenz’s fiancée, cannot meet her that night, brother and sister decide to walk to the cottage where Krescenz and Karl will begin their married life.[8] The fact that Mulholland spent formative early years as an apprentice visual artist is evident in Krescenz’s scenic descriptions of the river and its surrounds: the ‘gloriously blue’ Moselle, and the ‘magnificent … red light …upon the vine-covered banks, with the crimson earth glowing between!’ (1909, p. 122). Like Mulholland, Krescenz has artistic aspirations. Confiding in her brother, Krescenz also voices the reasons for her curbed ambitions: ‘If I had been a man, Max, I should certainly have tried to be an artist. Karl laughs at me when I say so; he does not care for such things, and gets annoyed when I talk about them; and yet I never saw half the beauty of things till he loved me’ (1909, p. 122). Despite Max’s concerns, Krescenz persists in her belief that Karl loves her and imagines the kind of life they will have together. As they walked, the

‘sister and brother turned their steps toward a pleasant summer-house of refreshment, built among trees, upon the high over-hanging bank of the river, where the people of Trier love to drink coffee in the cool of the evening. As the girl and child took their simple meal in the nook of the projecting terrace, the blue Moselle rushed under their feet, and Trier lay bathed in ruddy glory in the distance before their eyes, with its strange contrasting outlines softened into magnificent harmony, and the fierce black Roman gates making a frown on the very front of the sunny landscape’ (1909, p. 124).

Continuing their rambles on the hillside beside the river, Krescenz’s idyll is shattered when Max glimpses a pair of lovers. It turns out to be Karl and Luise, a girl that Krescenz knows. Contrasting the purity of Kreszenz’s love with the faithless Karl’s betrayal, Mulholland’s story ends with a tragic and haunting picture of Krescenz and Max: ‘Deepening shadows dropped on the Moselle, and the two young figures hurried on through the purple twilight away from Trier’ (1909, p. 125).

‘the red light paled on the Moselle’

As we literally traced those ghostly footsteps in the city, we were also learning to apply digital methods to our Rosa Mulholland dataset which, to date, extends to 551 publications (including serialised stories), over a diverse range of periodicals and newspapers. The Digital Humanities team in Trier introduced us to open source tools such as OpenRefine (https://openrefine.org/) which proved particularly valuable for working with our ‘messy data’, with options to clean it, transform it from one format into another (visualisations for example), and extend it with web services and external data. Brainstorming with the team also demonstrated the value of Linked Open Data and collaborative spaces such as Wikibase Cloud, which facilitate the global sharing of knowledge and information. One example of the uses of Linked Open Data that resonated is the TCDH MiMoText project (2019-23) with a focus on sources on the history of the French novel from 1751 to 1800, including access to some existing full-text digital copies. This particular project establishes ‘an information network for the humanities that is fed from various sources and … offers new and efficient ways of accessing specialist academic information by providing it as linked open data’.[9] Equally striking as a potential model for future projects is the recently launched large-scale ‘Princesses’ Libraries and Knowledge Practices in 18th-Century Germany: Reconstruction, Function, and Significance’, which aims ‘to structure and publish the comprehensive data from 99 private libraries, making them digitally available for free use by researchers’ (2024 – 2036)[10]. Models and tools such as these, and the free and open access options to work in collaborative digital spaces, are not only inspiring but also suggest future methods for energising the ‘digital renaissance’ of Mulholland’s work and that of her literary contemporaries. Production of meaningful knowledge from the cultural metadata collected is a project that has been and continues to be collaborative and generative.

Sincere thanks to the Director of the TCDH team, Professor Christof Schöch, Julia Röttgermann, Dr Maria Hinzmann, Dr Keli Du and Evgeniia Fileva for their generous welcome and support, and to CLS INFRA for this opportunity.

CLS INFRA has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 101004984.

Note: our thanks to Network blog editors and readers, Whitney Standlee, Caoilfhionn Ní Bheacháin and Sinéad Mooney for their valuable responses to this piece, and thanks to Deirdre Flynn for preparing and posting.

[1] Lady Gilbert (Rosa Mulholland). (1909) ‘Krescenz: An Idyl on the Moselle’, The Irish Monthly, 37(429), 121–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20502576. Belfast born Rosa Mulholland, Lady Gilbert (1841-1921) published across a diverse range of Irish, American, Australian as well as British newspapers and magazines.

[2] A larger bibliographical dataset developed by Geraldine Brassil maps Irish women contributors across diverse Catholic-orientated publications (1851-1921).

[3] The Irish Women’s Writing (1880-1920) Network https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/

[4] This project has benefitted from the research of other scholars including a range of publications by James H. Murphy, e.g. (2021) Rosa Mulholland: Feminist, Victorian, Catholic and Patriot, Brighton: Edward Everett Root, Publishers, Co. Ltd. and Margaret Kelleher, e.g. (2006) ‘Prose and Drama in English 1830-1890: from Catholic emancipation to the fall of Parnell’ in Kelleher, M., and O’Leary, P., eds. The Cambridge History of Irish Literature: Volume 1: To 1890, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 449-499; also Maria Mulvaney, (2021) https://ghostlyirishfictions.com/2021/12/09/rosa-mulholland-further-reading-and-resources/; Marguérite Corporaal PI et al., Redefining the Region: The Transnational Dimension of Local Colour https://redefiningtheregion.rich.ru.nl/persons/detail_person/1004; William G. Contento and Phil Stephensen-Payne, ed., The FictionMags Index http://www.philsp.com/homeville/fmi/n07/n07384.htm#A102; Bruce Stewart, Ricorso, http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/m/Mulholland_R/life.htm; Richard Dalby (2019) ‘Introduction’, Not to be Taken at Bedtime and Other Strange Stories by Rosa Mulholland, Dublin: Swan River Press, https://swanriverpress.ie/tag/ghost-stories/.

[5] Examples include: The Reception and Circulation of Early Modern Women’s Writing, 1550-1700, https://recirc.universityofgalway.ie/ or the Modernist Archives Publishing Project, https://www.modernistarchives.com/.

[6] ‘Computational Literary Studies Infrastructure (CLS INFRA) is a four-year partnership to build a shared resource of high-quality data, tools and knowledge to aid new approaches to studying literature in the digital age’. https://clsinfratna.sciencescall.org/resource/page/id/8. We are grateful to Dr Sarah Hoover and the CLS INFRA Transnational Access Fellowship team for their support.

[7] Mulholland’s story appeared in a 1909 issue of the Irish Monthly, but it had already been included in her 1880 short story collection of mainly ghost stories, The Haunted Organist of Hurly Burly. Many of the tales in this collection had been published earlier in Charles Dickens’ All the Year Round (see Richard Dalby, https://swanriverpress.ie/tag/ghost-stories/). As a travel writer, the Trier story may well have been inspired by an earlier journey that Mulholland made. An 1874 ‘travel letter’ from Antwerp, ‘Our Foreign Postbag: An Untravelled Islander Abroad’ in the Irish Monthly, forexample,suggests that more letters were to follow, however none have been recovered to date. In Trier in 2025, retracing the walkways that the story follows, we can only speculate that Mulholland visited the city, though it seems very likely given her accurate descriptions.

[8] Trier was the birthplace of Karl Marx in 1818. Given this and multiple visual and cultural references around the city, the Karl Marx House Museum, Karl Marx Strasse and an enormous bronze statue, Mulholland’s choice of names for her male characters, Karl and Max, took on a new resonance when rereading the story. Coincidence more than likely, but it was another serendipitous moment of crossings and connections.

[9] (Mining and Modeling Text – MiMoText | KOMPETENZZENTRUM – TRIER CENTER FOR DIGITAL HUMANITIES).

[10] https://tcdh.uni-trier.de/en/projekt/princesses-libraries-and-knowledge-practices-18th-century-germany

Dr Kathryn Laing

Dr Kathryn Laing (Department of English Language and Literature, MIC, University of Limerick) is co-founder of the Irish Women’s Writing Network (1880-1920) https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com and general editor with Dr Sinéad Mooney of two series, Key Irish Women Writers and Irish Women Writers: Texts and Contexts (EER Publishers). Her research interests are principally in late nineteenth-century Irish women’s writing, modernism and modernist women writers. Recent publications include: Laing, Kathryn and Iliana Theodoropoulou. ‘Lost and found in the archives: Hannah Lynch and Dimitrios Vikélas; Dublin, Athens, Paris: literary crossings and collaborations’, Irish Studies Review 31.4 Nov 2023, 1-19; Laing, Kathryn, Sinéad Mooney, Caoilfhionn Ní Bheacháin, Anna Pilz, Whitney Standlee, and Julie Anne Stevens. “Connecting Voices: An Introduction to Irish Women Writers’ Collaborations and Networks, 1880–1940.” English Studies 140, no. 5 (2023): 1–21; Laing, Kathryn and Mary Pierse, eds. George Moore: Spheres of Influence (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2023); Laing, ‘F. Mabel Robinson, Vernon Lee, and George Moore: The Aesthetics of Sympathy and Texts of Transition’ in Re-Reading the Age of Innovation: Victorians, Moderns, and Literary Newness, 1830-1950, ed. Louise Kane (London: Routledge, 2022); and Laing, ed. Hannah Lynch’s Irish Girl Rebels: ‘A Girl Revolutionist’ and ‘Marjory Maurice’ (Brighton: EER, 2022).In 2024 she was awarded a CLS INFRA (Computational Literary Studies Infrastructure) Transnational Access Fellowship, in partnership with the Trier Center for Digital Humanities, to work on a collaborative digital project with Geraldine Brassil.

Dr Geraldine Brassil

Dr Geraldine Brassil (Department of English Language and Literature, Mary Immaculate College (MIC), University of Limerick) holds a Government of Ireland Postdoctoral Fellowship. Prior to this she was a Teaching Fellow in the Department of English Language and Literature, MIC (2023-2024). As a PhD student she was awarded an IRC 2020 Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship. Her work focuses on the study and recovery of nineteenth century Irish women writers and evolving print cultures in contemporary publishing contexts. She is an assistant researcher with the Irish Women’s Writing (1880-1920) Network. In 2024 Geraldine was awarded a CLS INFRA (Computational Literary Studies Infrastructure) Transnational Access Fellowship, in partnership with the Trier Center for Digital Humanities, to work on a collaborative digital project with Kathryn Laing. Geraldine’s published articles include, ‘Women’s Collaborative Literary Processes and Networks: Mary and Matilda Banims’ Ireland’, English Studies, published online: 20 November 2023 and ‘Feminist Networks Connecting Dublin and London: Sarah Atkinson, Bessie Rayner Parkes, and the Power of the Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press’, Victorian Periodicals Review (Spring 2022). She has also published ‘Essays on Woman’s Work (Rayner Parkes)’ and ‘English Woman’s Journal’ In Scholl L (eds), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women’s Writing. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. (2021).

This publication has emanated from research conducted with the financial support of Taighde Éireann – Research Ireland under Grant number GOIPD/2024/490.