Collaborations and Networks symposium 2021

Conference

The symposium, September 3 – 4, 2021 explored the various ways in which Irish women writers engaged in and developed diverse creative collaborations in order to produce a wide range of works. It investigated how they created their material(s), sometimes crossing over from one media to another or seeking avenues for publication outside of traditional routes. In doing so, the symposium considered not only the ways in which women crossed borders but also the extent to which they managed to embrace multiple places at the same time.

For more on the conference line-up click here.

Special Events

Book Launches

Interview with leading theatre director, Garry Hynes

Garry Hynes, Druid Theatre Company, interviewed by Network Team member Anna Pilz

Co-ordinated and convened by Network Team member, Julie Anne Stevens

For more on Druid Theatre Company click here.

New York Irish Center Panel

‘Irish Women’s Writing Past and Present in the North American Context’ Irish writer and journalist Sadhbh Walshe led a panel of Irish women writers based in the United States: Yvonne Cassidy, Emer Martin, and Belinda McKeon.

Co-ordinator: Network Team member, Dr. Julie Anne Stevens, Dublin City University

With thanks to New York Irish Center Executive Director, George Heslin.

For more on the work of the New York Irish Center click here.

Book Launches

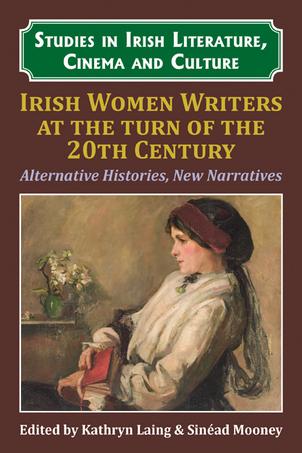

Irish Women’s Writing at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives, edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney

Launched by Pilar Villar-Argáiz

It is with great pleasure and excitement that I launch this title of the major series of Irish Studies published by Edward Everett Root: Irish Women’s Writing at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives, edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney and published in association with the Irish Women’s Writing Network, 1880-1920. I was truly delighted to work with these two wonderful editors, consolidated and admired scholars in the field. In line with the title of this wonderful symposium, “Collaborations and Networks”, it is precisely this kind of professional collaboration what truly gives meaning, what eventually gives sense to our professional life and I was simply blessed by this sense of liaison, of fluid connection, that I experienced with the two editors. They made things very easy and they truly did a wonderful job.

The collection gathers research on Irish women’s writing at the turn of the twentieth century by recognized scholars and early career academics, thus illustrating the ethos of the Irish Women’s Writing Network, which encourages such international and interdisciplinary conversations and collaborations. It is partly based on the research first presented at the editors’ symposium of the association at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, in 2016 where the network was also launched. The essays collected here make a fine, key contribution to contemporary feminist recovery projects. They discover new voices and introduce original perspectives on the lives, works and networks of more familiar literary figures.

Just by looking at the content we get an insight into the fresh, engaging and timely quality of the work presented here.

In the Introduction, “A Palpable Energy”, the Editors offer an exhaustive critical overview of contemporary feminist literary and cultural recovery projects in Ireland. The title comes after Margaret Kelleher’s assertion, in 2016, that “we are in a better place as critics and teachers”, given the “palpable energy” in Irish writing, publishing and criticism. This monograph clearly contributes to energising such debate in Irish studies, engaging in a rich conversation on issues of retrieval, representation and reconsideration of female voices in history and literature.

The collection is efficiently divided into 2 sections, “New Perspectives” (with 9 essays) and “Recoveries” (with 7 essays), making an overall of 16 essays in total.

The first section “New Perspectives” opens with a fine essay by Maureen O’Connor, “Nation and Nature in the Work of First-Wave Irish Feminists”. In this impeccably well documented chapter, O’Connor offers an eco-critical exploration of Eva Gore Gooth’s pacifism alongside the work of other fellow feminists such as Margaret Cousins and Charlotte Despard, among others.

The second chapter by Seán Hewitt also draws from an eco-critical perspective, this time to approach the well-known work of Emily Lawless. This is an entirely new, fresh perspective on this writer, as Hewitt identifies her as a natural historian, underscoring her modernity and her challenge of the positivism of scientific orthodoxy.

In the third essay of this section, “Sunk in the Mainstream: Irish Women Writers and Famine Memory”, Christopher Cusack offers well-documented examples of the portrayal of the Famine in forgotten novels and short stories by Jane Barlow, Louise Field and Mildred Darby, among others, challenging the persistent belief that the memory of this traumatic historical event has been repressed in Irish literature.

This chapter is followed by Lia Mills’ powerful account of Eva Gore-Booth’s poetic involvement with the Easter Rising and World War II. As Mills convincingly reveals, Gore-Booth’s commitment to non-violence was a core dimension of her character, and it was founded on spiritual principles that were esoteric.

The fifth chapter by Julie Anne Stevens explores female visual artists’ international networks by examining in detail the relations established in the diaries, artwork and sketchbooks of Edith Somerville and Martin Ross. This scholar demonstrates how feminist discourse was well established at the end of the 19th century, and how new subversive ideas about femininity were introduced to Irish readers through the aforementioned women artists.

Edith Somerville’s empowerment of female identities is also the concern of the essay that follows by Anne Jamison. Jamison offers relevant research of Somerville’s subversive adult fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood in Kerry”’, exploring in convincing ways the construction of images of female empowerment through metaphors of fox-hunting and other coded images of Irish folklore.

The collection follows with two essays on the New Woman novelist from Cork Katherine Cecil Thurston. In his eloquent chapter “A Thing of Possibilities: The Railroad and Cosmopolitical Belonging in Thurston’s Max”, Matthew Reznicek draws on her 1910 novel Max, in order to identify feminist “geographies” of nomadism.

On her part, Sinéad Mooney convincingly examines her work in order to look at the representation of diseased and deranged male characters in her novels, in terms of the fin-de-siécle discourse of degeneration.

This first section closes with an essay by Aintzane Legarreta Mentxaka, which considers George Egerton and Emily Lawless as Irish ‘New Woman’ writers. Legarreta particularly examines politicized tropes of silence in their fiction, revealing what we could call the “deep realism” of psychological modernist fiction.

Recoveries

The second section in the collection, entitled “Recoveries”, is composed by 7 essays which contribute to remapping the landscape of Irish literature of this period, as they shed light on authors or bodies of work rarely or never been considered before in Irish academia.

This section opens with a fine essay by Heidi Hansson, which eloquently examines how Irish women contributors negotiate their claims to authority and activism in intellectual Journals such as the Nineteenth Century.

Elke D’hoker, on her part, brings to light the neglected figure of Ethel Colburn Mayne, by discussing her short stories and restoring her presence as an original, consummate writer who anticipated subsequent Anglo-Irish writers.

Elizabeth Priestley is also another figure who certainly deserves renewed attention, as Mary Pierse shows in the following chapter. By drawing on county archives and libraries, Pierse rediscovers the presence of this spirited writer, feminist, and suffragist from County Down.

Indeed, all the chapters in this section are driven by this need to recover figures who have been largely neglected both in history and literary criticism. Patrick Maume in chapter 13 rescues the life and work of the Presbyterian writer Erminda Rintoul Esler advocating further research on this figure and focusing on themes in her work such as Education, Love, Loneliness, and Philanthropy.

In her engaging essay, “From Special Correspondence to Fiction: Memory and Veracity in Margaret Dixon McDougall’s Writings on Ireland”, Lindsay Janssen examines the journalism of this member of the Irish diaspora, “hoping (in her own words) to increase understanding of the religious and social contexts with which she engaged”.

On his part, Barry Montgomery presents innovative research on Hannah Berman, one of the earliest Irish-Jewish writers, who migrated to Ireland at the turn of the century and had an active role in Dublin literary networks.

The book finishes with a essay by Lisa Weihman, Mothers of the Insurrection: Theodosia Hickey’s Easter Week”. This illuminating chapter adds innovative findings in the field of Irish women’s writing about war and the Irish revolutionary movement.

In short, this publication, I believe, will be landmark in the field, and testifies the fruitfulness, richness and benefits of establishing interdisciplinary connections in the study of Irish women’s writing. This is the ‘palpable energy’, in words of Margaret Kelleher, of this collection, which underscores how the process of recovering and revising female figures from the past will always be ongoing, unfinished process. Thanks Kathy and Sinéad for sharing, maintaining, keeping alive the light of this ‘palpable energy’ with us, with this community, this family, of Irish scholars. And thanks for counting on the major series of Irish Studies in EER for publishing this astonishing collection.

Irish Women Writers: Texts and Contexts series:

Ethel Colburn Mayne: Selected Stories, edited by Elke d’Hoker

Rosa Mulholland: Feminist, Victorian, Catholic and Patriot, edited by James H. Murphy

Key Irish women writers Series:

Elizabeth Bowen, by Heather Ingman

Maria Edgeworth, by Clíona Ó Gallchoir,

Launched by Maureen O’Connor, @irishecocritic

Today I am launching two publications each from two different series, published by Edward Everett Root, and, in both cases the series editors are Kathryn Laing and Sinead Mooney.

Books in the “Irish Women Writers: Texts and Contexts” series are critical editions of hard-to-find examples of work by writers who have been disregarded or under-appreciated or even forgotten. The editors of these books provide biographical and historical contexts, as well as helpful annotations, and extensive bibliographies. The two entries being launched today are Ethel Colburn Mayne: Selected Stories, edited by Elke d’Hoker and Rosa Mulholland: Feminist, Victorian, Catholic and Patriot, edited by James H. Murphy. They will soon be joined in this series by a forthcoming volume on Hannah Lynch, Hannah Lynch’s Irish Girl Rebels, edited by Kathryn Laing. Volumes in the “The Key Irish Women Writers” series offer relatively short critical introductions to, as it says on the tin, key Irish women writers, some well known, some undeservedly obscure. The entries being launched today, Elizabeth Bowen, by Heather Ingman and Maria Edgeworth, by Clíona Ó Gallchoir, will soon be joined by volumes on Kate O’Brien and Jane Wilde. One of the first things that strikes anyone looking at the contributions to the two series is the eminence of the authors and editors included in the line-up. The two authors just mentioned, for example, Ó Gallchoir and Ingman, co-edited the 2018 Cambridge A History of Modern Irish Women’s Literature, one of the recent examples of attempts that scholars have been making in the last thirty years or so—since volumes 4 and 5 of the Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing—to begin to do justice to a long, but occluded history of women writing in Ireland.

While most of the writing done by Irish women up to the eighteenth century, and possibly much after, is lost to us, women had been writing religious tracts, cookery books, poetry, petition‐letters, etc., for generations. Irish women writers nurtured, inspired, parodied, collaborated and competed with men, as well as with each other. The women writers who are the subjects of the books being launched here are not just inheritors of a tradition but are among a number of women writer who have been instrumental in establishing Ireland’s international reputation for literary production. This is a fact that might be self-evident to many of us here, but which seems to bear repeating, as the debacle of the centenary commemoration programme announced by Abbey Theatre in 2016 demonstrated, a piece of patriarchal revisionist history which inspired the Waking the Feminists protest movement

The struggle for women writers to be acknowledged in their own lifetimes is a struggle that must take into account the historical as well as the contemporary; the circumstances of the creation of the work and the fate of the work, the writer’s reputation in the intervening period; the individual artist and the collective of which she is a part. All of the books being launched here do a fantastic job of that, giving us a rich context for the writing as well as an impressively comprehensive picture of the current state of analysis and critique of that work, what research has been done, what is left to do. In their 2019 study of the life and writing of Irish writer Hannah Lynch, Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing say of their subject, “Lynch was well aware that ‘biography’ and ‘history’ are genres open to subversion, deformation and play, and that women’s lives are particularly vulnerable to misinterpretation.”[1] This observation could act as a kind of guiding principle for these series and is something that the subjects of these works were well aware of themselves; I’m thinking of Mayne’s biography of Lady Byron, much admired in its times. That work gave us new insight into Byron himself as well as his milieu. This is something I learned from Elke d’Hoker’s introduction!

The Binckes and Laing book I just quoted offers a glimpse not only into the life of a neglected Irish writer, famous in her time, but also into a robust international women’s culture at the fin-de-siècle—the period of central though not exclusive interest to the IWW network—a woman’s culture that only recently has become the subject of critical revival, to which Irish writers, artists, journalists, and activists contributed significantly. All of the books being launched today similarly reveal an officially submerged context, the disavowed truth of the collaborative structure of any writing achievement, however cloaked in romantic mystery in order to serve the myth of the solitary genius, a myth usually associated with the male writer. No such placatory, assuasive fictions are available to the woman writer.

In her 2016 study of the collaborative relationship of the Irish writers Edith Somerville and Violet Martin (penname Martin Ross), Anne Jamison describes the “hero-artist of the late nineteenth century”[2]: male, solitary, questing, in pursuit of lofty artistic achievement. The fin-de-siècle period was one during which distinctions were hardening between “low” popular culture (predominantly produced by women writers) and works of “high,” properly “literary,” value, a distinction that worked to preserve “the honour of succès d’estime from the taint of fashionable recognition and economic reward.”[3]

Most of the writers who will be included in these series emerged from a wide and enabling community of support, not something that can be taken for granted as a given. Women writers could not and for the most part still cannot simply wait for the applause, the celebration the creative genius expects as his due. The networks described in these recent retrievals require constant maintenance and nurturance, because fragile, threatened, undervalued when not entirely disregarded, and are the subject of Deirdre Brady’s hotly anticipated book, being launched in a few minutes, Literary Coteries and the Irish Women Writers’ Club (1933-1958). Networks of support and collaboration—and these categories shade into each other, perhaps especially in the case of women artists—often structured by emotional ties, are difficult if not impossibleto reconstruct faithfully, by their very nature. The “feminine” ephemera of affect , gossip, and intimate relationships elude transcription and preservation, a suggestive, haunting absence from the archive shared with the nonhuman contribution to the work of art, also referenced earlier. Ephemera are not valued in a culture that emphasises the importance of achieving immortality through enduring monuments to genius.

What I am increasingly learning about Irish women writers of this period is that they were working with a relational sense of self that has the potential to reform social and gender relations. There are a number of foundational, western ideas of the self and the artist that have ramifying consequences that the women discussed in these series were challenging over a hundred years ago in some cases, over 200 year ago in the case of Edgeworth. Another thing this kind of research is revealing to me is the nearly bewildering variety of outlets for writers of all kinds in this period. Hannah Lynch, Rosa Mulholland and Ethel Colburn Mayen were key players in the publishing culture of the fin-de-siècle period, especially when it came to periodicals, magazines, journals, and newspapers. James H. Murphy notes that Matthew Russell, editor of the Irish Monthly considered Rosa Mulholland as key to the magazine’s success. Without her “the magazine would not have survived and thrived” in its first twenty-five years and, according to Murphy, “someone quipped it ought to be renamed the Irish Mulholland.”[4] Charles Dickens, in his role as editor of All the Year Around, also recognised Mulholland’s talents, and her short story ‘The Hungry Death’, which he published in the periodical, was chosen by W.B. Yeats for inclusion in his 1891 volume, Representative Irish Tales.

Ethel Colburn Mayne frequently published in and was co-editor of The Yellow Book when it was edited by Henry Harland, a signal influence on the development of her literary style. The quality of Mayne’s fiction was recognised by fellow writers like Elizabeth Bowen, Ford Madox Ford, and Christopher Isherwood, and she was regularly compared to Henry James and Katherine Mansfield. But somehow she is unknown to us today! I was fascinated to learn that she was acquainted with Joan Riviere, author of the famous feminist work, written decade before Judith Butler was even born, Womanliness as a Masquerade (1928). As I have argued elsewhere, the feminists of this era were very much ahead of their time, anticipated what we think of as cutting edge postmodern, posthumanist insights. The narrative d’Hoker provides of Mayne’s development of a psychologically sophisticated modernist style is one of the introduction’s most satisfying achievements.

Despite Isherwood recognising Mayne’s “quite unladylike Irish wit,”[5] d’Hoker observes that her work “falls outside nationalist definitions of the Irish canon,”[6] a fate shared by many of the writers featured in these series, including Elizabeth Bowen, Hannah Lynch, and even Maria Edgeworth because of her birth and early childhood in England. Murphy notes of Mulholland and other contributors to the Irish Monthly that they have “been overlooked in the attention given to the literary revival.”[7] Narrow definitions of nation as well as quite strict geographical limits on identity contribute to this vexed question, something that likely contributes to these writers falling out of collective memory. It is not only the contributors to the Irish Monthly who have been overshadowed by the Revival narrative of Irish literature, which has written out of received official history the lively cosmopolitanism of Irish literary culture in the first half of the twentieth century.

To turn now to the volumes on Bowen and Edgeworth, both provide deftly sketched analyses of numerous texts. The studies are pacey, arresting, and somehow manage to be both academically informed and admirably accessible without compromising any scholarly texture. They are enormously enjoyable reads, positioning their subjects within their own contemporary contexts and within our contemporary academic moment.

Ingman’s approach to Bowen and her work takes seriously the author’s religious faith, something of central importance to Rosa Mulholland as well. This angle on Bowen’s work offers something genuinely new and insightful, not easy to do when so much has been written about Bowen in recent decades. Ingman also excavates the sometimes subterranean Irish layers to Bowen’s oeuvre while making important points about the difference between Bowen’s Irish stories and Frank O’Connor’s formula for the Irish short story, one which is not always easy to map onto women writers’ short fiction. I always appreciate attention to form, and while the formal qualities of Bowen’s work is an expected part of any analysis, I was delighted to learn something about Edgeworth’s evolution of style over the course of her career, something I have not seen attract much critical attention. The Edgeworth of Ó Gallchoir’s new study is at once familiar and thrillingly new. I felt like the heroine of a rom-com who sees her long-time, comfortably beloved friend turn into someone to fall passionately in love with. It is worth remembering, as Ó Gallchoir notes, that Edgeworth was significant to the development of the very genre of the novel, even as she created polyphonic, hybrid forms of fiction that defy categorisation. Ó Gallchoir discusses the ways in which Edgeworth’s fiction negotiates the relationship between the private and the public in Irish social life, providing a bridge between these realms, a theme recurring in many of the discussion in these books: that is, the idea of the woman writer acting as a bridge, a perhaps not always glamorous, appreciated, or noticed writerly function. D’Hoker suggests that Mayne “bridge[s] the gap between fin-de-siècle Aestheticism and early twentieth century modernism.”[8] Mulholland’s short stories, especially her sympathetic portraits of the “peasant” Irish, attempted to span the gulf of misunderstanding and miscomprehension that sometimes yawned between Ireland and England at the time, while Bowen, similarly to Mayne, brings the symbolist aesthetics of Irish writers like Yeats and Wilde into the jet age of the 1960s with her late novels.

These series of books on Irish women writers might also be characterised as creating a bridge between these women writers and our own current preoccupations and continuing struggles. Perhaps more significantly, they open paths to future work, not only introducing scholars to writers about whom little has yet been written, but also demonstrating the possibility of fresh new readings and approaches to writers firmly positioned within the Irish canon like Edgeworth and Bowen. All of these books were an absolute pleasure to read, and I thank the series editors for their hard work and for enabling my access to the texts. I also applaud the authors and editors for their illuminating, entertaining, and important work. Congratulations, all!

[1] Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing, Hannah Lynch (1859-1904): Irish Writer, Cosmopolitan, New Woman (Cork University Press, 2019), p. 7.

[2] Anne Jamison, EΠSomerville and Martin Ross: Female Authorship and Literary Collaboration (Cork University Press, 2016), p. 4.

[3] Ibid., p. 6.

[4] James H. Murphy, ed., Rosa Mulholland: Feminist, Victorian, Catholic and Patriot (Edward Everett Root, 2020), p. xiii.

[5] Elke d’Hoker, ed., Ethel Colburn Maye: Selected Stories (Edward Everett Root, 2020), p. 1.

[6] Ibid., p. 3.

[7] Murphy, p. xvii.

[8] d’Hoker, p. 34.

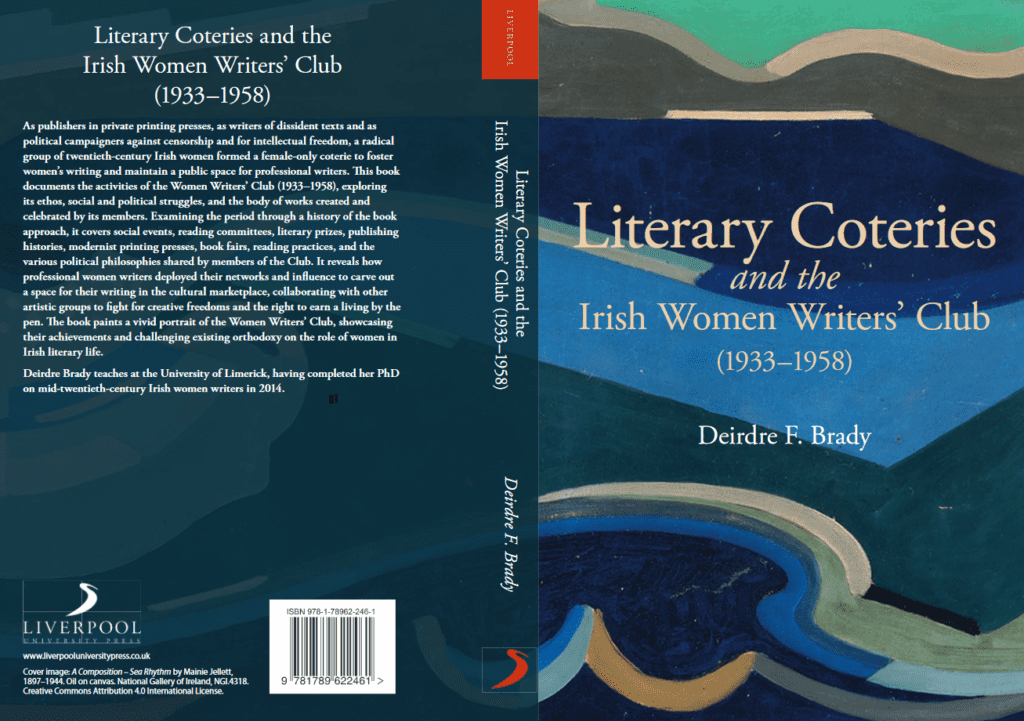

Literary Coteries and the Irish Women Writers’ Club (1933-1958)

Deirdre Brady

Deirdre Brady

This book focuses on the social, political, and literary lives of pioneering women who fought for their right to ‘earn a living’ by the pen and have their voices heard. It offers insights into the importance of networks and connections to the reception of books and the power of friendships and affiliations in supporting intellectual endeavours. Exploring political activities, literary prizes, ‘at homes’, publishing histories, book fairs, and the impact of private printing presses, this book reconstructs history, bringing women writers back into the fore and showcasing the impact of coterie culture in shaping the literary landscape. The book is part of a series in English Texts and Studies published by the Liverpool University Press in July 2021.

The story of the Women Writers’ Club begins in 1933 when more than twenty women attended an inaugural meeting at 43 Morehampton Road: home of the renowned poet and salonnière Blanaid Salkeld. From a modest gathering, it built up a reputation as a force for change with its impressive membership list. Notable writers such as Elizabeth Bowen, Helen Waddell, Kate O’Brien, Maura Laverty, Dorothy Macardle, Patricia Lynch, Blanaid Salkeld, Temple Lane, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Rosamond Jacob, Nora Connolly O’Brien, Lorna Reynolds, Christine Longford (Countess of Longford) and Teresa Deevy formed part of this coterie of literary women. As a supportive circle where relationships were cemented and encouraged, the book explores the power of this collaborative network in fostering women’s writing, defending criticisms, and lending literary authority to their works.

As social visionaries advocating for change, influential activists and international feminists formed part of the cultural milieu surrounding the Women Writers’ Club. As a collective, they fought tirelessly against censorship, standing up for the rights of professional women, and lobbying as a collective against the draft Constitution 1937. What emerged from this period was a united, politicized female group of writers connected through cultural and social networks, who were fully intent on using the power of the pen to express their art in a form that was determinedly female, oppositional and in many cases radical. Consciously aware of their marginal status, they initiated a literary prize, The Book of the Year’ and launched newly published books at their annual banquet, celebrating an alternative corpus that denotes a specific feminist sensibility; and one that ardently championed autonomy, independence and equality for women.

Spatial geographies are critical to this investigation in terms of shared social spaces where publishers, writers, actors, and like-minded male and female intellectuals mingled in the Dublin’s vibrant city centre. The book begins by redrawing the literary map to include the meeting points of an engaged female literati while offering an account of dominant writing groups including the Irish Academy of Letters, and Irish PEN, and their relationship with the Women Writers’ Club.

The scope of the book extends to a discussion of reading committees, publishing histories, and literary events. Thus, the first Irish Book Fair 1941 is explored, revealing new insights into the reading public and their support for Irish writers. So too, cultural practices of intellectuals such as that of Rosamond Jacob, evinced from her diaries, yields rich insights into intellectual thought, social mores, and attitudes of the period. Private printing presses as vehicles for disseminating ideas are explored through the history of the Gayfield Press, a private printing press owned by Blanaid Salkeld, the founder of the Women Writers’ Club. This book offers the first comprehensive history of this press, opening the discussion of the role of women in publishing, modernism, and the influence of networks and connections to cultural production.

Examining the period through a history of the book approach broadens the scope for probing the interactions which constitute book production and the communication processes which affect the transmission of texts. Thus, historical records, published and unpublished, alongside a diverse array of material from private correspondences to bibliography lists are examined as a way of offering new understandings of the period.

This book aims to begin the conversation about how we can conceptualise Irish women writers as central participants in the intellectual public sphere, then, and now, and appreciate the web of interrelationships that connect writers with the cultural marketplace.

For more information, see https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/books/id/55349.

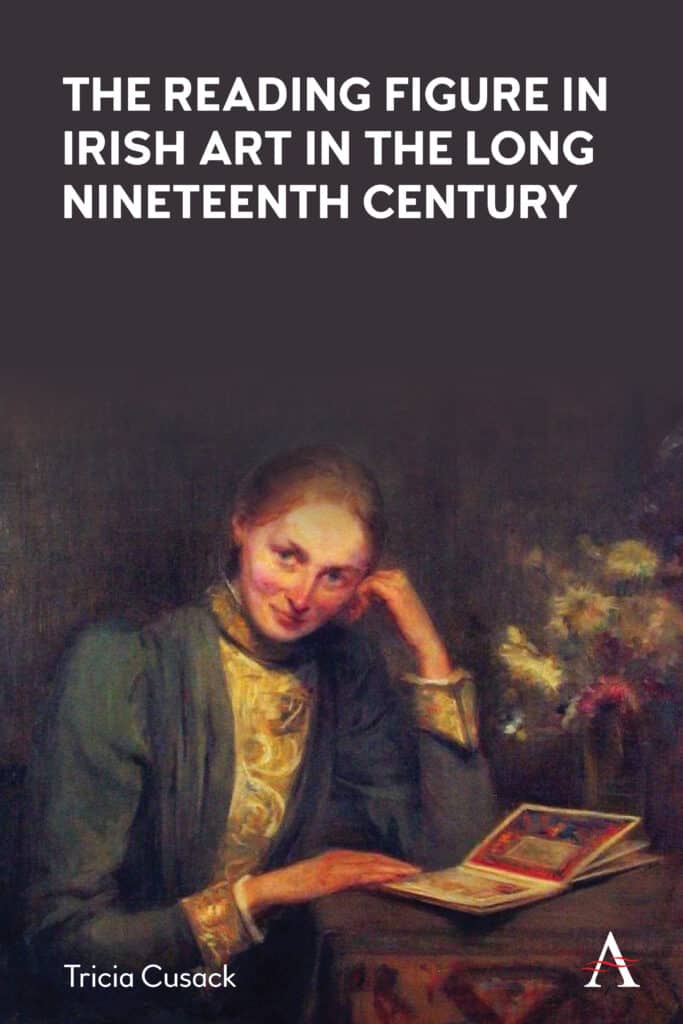

The Reading Figure in Irish Art in the long Nineteenth Century: A brief introduction

Tricia Cusack

Tricia Cusack

Working on my book The Reading Figure in Irish Art in the long Nineteenth Century has been great fun and finishing it leaves me a bit bereft!

It explores Irish portraits of figures shown reading or accompanied by a book. ‘Irish art’ is broadly interpreted to include artists trained or practising in Ireland. The ‘long nineteenth century’ is given an Irish dimension, taking it from about 1801, marking the Union of Ireland with Britain, to the watershed of the Irish Rising of 1916.

Here are some of the book’s themes:

- It examines contemporary constructions of ‘manliness’, their impact on men’s reading, and how this was reflected in contemporary portraiture.

- It argues that Dublin by the later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century was a space of special creativity and artistic and cultural leadership among women, at least those from the privileged classes.

- It considers the prevalence of ‘silent reading’, with the spread of the novel and their implications especially for women.

- The book shows how visual art contributed to the representation and the formation of the emergent ‘New Woman’ in Ireland at this time.

There are five chapters, which I’ll very briefly summarise.

Chapter 1 asks why countless public portraits of men rarely depict them reading. I argue that reading for pleasure, especially fiction, was not valued as a manly pursuit by either imperial or nationalist ideologues. If a male figure is portrayed with a book, this generally functions in a traditional way as a symbol of his profession.

Chapter 2 argues that while the woman reader has been a recurrent theme in European art, especially from the nineteenth century, the figure was usually shown with an emphasis on bodily display for a secret viewer, rather than depicted as a reader. For example, a female figure is shown reading, but presented semi-dressed in her boudoir.

Chapter 3 explores the idea of the New Woman. I argue that this was a transnational concept and that it emerged in Ireland from a confluence of factors, predominantly among the Anglo–Irish. It was associated with the campaigns for women’s suffrage, and as Tina O’ Toole has pointed out, with the work of the Ladies Land League. Importantly, the New Woman was constituted through literature and visual art.

Chapter 4 focuses on reading in relation to the New Woman and on the Irish portraits. It shows how the New Woman was nurtured by a habit of independent reading. It argues that the new prevalence of ‘silent reading’, alongside the spread of the novel, allowed women of means to engage privately with a new range of imaginative and intellectual reading materials. Silent reading also offered seclusion from patriarchal surveillance. In this context, the chapter examines a number of paintings in Ireland in this period, mainly by women artists, that depict a woman absorbed in a book and oblivious to any imagined spectator. Such representations of women as serious readers contradicted common constructions of them as consumers of lightweight romances. Images of female subjects absorbed in reading could also serve as a trope for an independent woman with private thoughts. I argue that these Irish portraits of women readers helped to constitute a typology of the New Woman as literate, focused and reflective.

Finally in Chapter 5, I focus on four New Women in Dublin, the artists, Sarah Purser and Estella Solomons, and the subjects of two of their portraits of readers, Jane Barlow and Alice Milligan. All four were key figures among the successful women artists and writers of this period.

To conclude, I wish to thank the various individuals and organisations that have helped with this project. I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments I have taken account of as far as possible. The book will have 30 illustrations in colour and black and white and I would like to thank the trustees of the Marc Fitch Fund for their financial assistance with the publication of these images. The book will be published in November and symposium members may pre-order the hardback edition from the publisher’s webpage at a 20% discount, using the code TCUS20. I hope you might want to purchase the book or perhaps ask your university library to do so. The publisher will also offer a purchasable PDF.