Mary Ann Allingham: An Introduction

by Dr. Niamh Hamill

MARY ANN ALLINGHAM 1820-1836

Will any one read my preface? (thought I to myself, as I sat down one evening with my Crow quill dipped in Indian ink in my fingers ready to begin an introductory page to my Friends . . . Will any one think it worthwhile to read a preface; not by an UNKNOWN AUTHOR (that would be, to be well known) but by an humble County Donegal Female. It was a stupefying thought, and the ink remained in the pen so long, that when my vanity decided that someone would read it: I was forced to clear the point of the congealed ink by my pen knife; and taking that as a lucky omen; here said I, “Female vanity, that sharp and never rusty knife, has cleared away those doubts and fears, Which ever buzz about poor authors’ ears.

—Mary Ann Allingham, Ballyshannon, 1833. [1]

Mary Ann Allingham was the aunt of Irish poet William Allingham.  Two volumes of her poetry and travel writing were discovered in an archive in Norway and were the subject of my dissertation in 2015.

Two volumes of her poetry and travel writing were discovered in an archive in Norway and were the subject of my dissertation in 2015.

Some of Mary Ann’s material was published under a pseudonym, and much of it deals with her happiness and unhappiness as a woman and as an aspiring writer living in Donegal, and as a middle-class Protestant. Her sense of authority and confidence is unusual for women’s writing at that time, – and her sources of happiness and unhappiness lie, respectively, in her ambition to be a writer, and the obstacles that were inherent in her gender and position.

Mary Ann’s texts might be said to belong primarily to two literary genres, that of travel narrative, and poetry. However, it is more accurate to say that she has produced texts that share a central theme of a desire to locate herself more securely in a literary and physical landscape that is barely accessible. There is a constant tension between her impulse to investigate, learn, and share her experience of her world, and an understanding that she is to be betrayed by time and circumstances, irrespective of all her discoveries. Consciously or subconsciously, Mary Ann is consistently wandering through cultural spaces, trying to grasp a foothold. The travel narratives are a literal expression of this limited mobility, the poems and verses are the metaphorical version. There is much overlap and intertwining, but the negotiation is consistent and urgent.

Travel writing and poetry were probably the two most masculine provinces of nineteenth century literature. [2] Elizabeth Bohls defines the implied subject of mainstream aesthetic discourse as “a gentleman: a privileged man, educated and leisured, an actual or potential property owner.”[3] Nineteenth century women writers who took on the discourse of aesthetics in travel narratives had to devise strategies of expression. In the case of a Protestant women writer such as Mary Ann, she was entitled by class, but limited by gender, to the authority of the aesthetic subject. Her texts reflect these contradictions and restrictions.

A feature of women’s poetry, notable in the work of Dorothy Wordsworth, was the omission of “a central or prominent self” from texts.[4] Mary Ann Allingham does not absent herself from her poetry; in fact, her concerns are frequently emphasised over those of others.[5] Unlike many nineteenth century women writers, Mary Ann makes herself the subject of many poems. Mary Ann is not an introvert, and frequently counterpoints self-deprecation with surprisingly assertive alliances with great writers of the time.[6] Her texts were not meant to be private- she courted not just readership, but publication. To borrow from Levin, Mary Ann not only was a woman “passionately concerned with putting words together”, but equally ardent that her words would be read.[7] Perhaps her authority in her domestic situation, combined with her sense of Anglican superiority, and the absence of a father, or spouse (until 1833), allowed her a kind of freedom that was unavailable to other women. In any case, there is an undeniable sense of conviction, of needing to express her world in words and verse.

Nature is a force in Mary Ann’s poetry; she uses it to illustrate the passing of time and the transience of human experiences. She rarely locates her poems indoors; social interaction and the contemplation of relationships consistently takes place in a setting filled with the dynamic energy of the ocean, the river or the weather. [8]The coastal landscapes and volatile weather of Donegal are usually present to some degree. Her own domestic and artistic concerns are frequently verbalized in terms of chaotic movement, and an absence of control.

An impressive feature of Mary Ann’s writing is her ability to cast off the brittle and sensitive self of her personal poems and to appropriate an antithetic voice; one of strident authority and, frequently, a sense of humour and irony, absent from those just considered. As Mary Ann strays into the domain of traditional male concerns, she appropriates the male voice and seizes a narrative jurisdiction not normally associated with nineteenth century women. [9]Mary Ann appropriates this voice to a certain extent in the travel narratives, adopting the scientific tone typical of antiquarian investigation, but then frequently disrupting the male authoritative voice with digressions of dramatic reconstruction. Her single-themed poems that are not part of larger narratives are more tightly formed and self-contained, and demonstrate a competent reworking of cultural prerogatives reserved for men.

Some of Mary Ann’s poetry is clumsy and derivative, some of it is varied and contradictory, but as Elizabeth Bohls points out, “sustaining and expressing contradictions in writing was a strategy for female psychic survival.”[10] The poems are not a literary treasure-trove, but they are a find for the cultural historian, and for the scholar of nineteenth century women’s writing.

The poems are her pitch for a rooted place from which to write, but her literary peripateticism emphasizes her instability. Her plaintive pleas not to be forgotten are more than the loneliness of a Ballyshannon woman; they reflect a desperate desire to find an alternative to the surrendering of her writer-self.[11] The most explicit articulation of this theme is a poem titled ‘I’m Lonely! I’m Lonely’.[12]

Mary Ann introduces the poem as follows:

These lines were written on the removal of the last of Four Friends; the companions of my childhood: now all scattered away like thistle down, leaving the stem, still in the ground, lonely and desolate looking.

Each verse opens with the title phrase, so explicit in its forlornness, that it is uncomfortable to read.

Her nostalgia is also a metaphor for the condition of Irish identity; Ulster, always the fault-line of the British-Irish relationship, is, like Mary Ann’s childhood, a landscape of remnants and flashes of a past that cannot be recaptured. She, (as many future Irish poets will do), ignores the ugly present and takes solace in the things that have remained constant; the flowing River Erne, the sunsets, and the ebb and flow of the ocean.

Mary Ann Allingham wrote without the benefit of a female literary tradition. The only “grandmothers” were legendary figures like Grace O’Malley or Walter Scott’s heroines.[13] Her search for female models to legitimize “her own rebellious endeavors” was fruitless; there were few, if any, literary precursors and her bitter disappointment in the failure of her contemporaries to test the boundaries of social behavior is evident throughout her work. [14]

In her travel narratives, she refocuses the gaze of her literary predecessors by replacing the language of utility with imaginative and dramatic reconstructions. She recognizes that the Irish architectural ruin is the absorption of history into nature, and she recovers history for the reader by repopulating the deserted castles, caves and coves with heroes and heroines from the Irish past.[15] In doing so, she pushes beyond a discourse of imperialistic calculation to a more romantic contemplation of “the days that are gone.” [16] In her ‘Excursion to Donegal’, published in 1829, she writes;

The castle of Donegal is a very beautiful, and if I may say so, perfect ruin of large extent. Through a gloomy vault you ascend, by a dark and spiral flight of steps, to a large room, lighted by three or four Gothic windows, commanding a noble view of Donegal bay, and the Killybegs Mountains. In this room are two fire-places, one of which has a curious mantle-piece of stone, of great breadth and height, carved with the O’Donnell arms and various other figures. The castle has evidently been much higher than it is now, as there is a range of windows and fire places above this room; but the flooring is quite gone, and the roof also…

The castle of Donegal is a very beautiful, and if I may say so, perfect ruin of large extent. Through a gloomy vault you ascend, by a dark and spiral flight of steps, to a large room, lighted by three or four Gothic windows, commanding a noble view of Donegal bay, and the Killybegs Mountains. In this room are two fire-places, one of which has a curious mantle-piece of stone, of great breadth and height, carved with the O’Donnell arms and various other figures. The castle has evidently been much higher than it is now, as there is a range of windows and fire places above this room; but the flooring is quite gone, and the roof also…

She interrupts the narrative for some of her own verses, reflecting on the history of this place;

Donegal,

A dull, yet pretty place,

Where stands the ancient ruined hall

Of the O’Donnell race

But time’s destroying hand rude falls

Upon the castle old;

And black and silent are its walls,

Once graced by heroes bold,

Oh! Who could climb its rude staircase

Or from its window gaze,

Or see its sculptured chimney-place,

Where once bright fires did blaze,

And think not of the busy feet

That scaled the steps so high;

To look upon the prospect sweet

Of ocean, mountain, sky.

Nor think of winter’s merry night,

How laugh and song went round;

How beam’d the eye with rapture bright,

With harps and bagpipes sound.

Now in the dust unknown they lie,

Gone is their once proud fame,

And wandering strangers, such as I,

Sigh oe’r O’Donnell’s name.[17]

Her poetry is uneven in quality and often frustratingly forced. This may not be simply because of a lack of natural talent. Terence Brown describes much of late eighteenth-century Ulster writing as “frozen in statuesque Augustan impotence”[18] Some of the awkward phrasing may be due to the influence of folksongs and balladry.[19]

The texts of Mary Ann Allingham are also important for the insight they provides into social and historical conditions of the early nineteenth century. Her texts contradict a current polemical cultural interpretation of the Protestant-Catholic relationship in Ulster. She demonstrates that antiquarianism was not only the pursuit of the intellectual. She presents, in her epigraphs and footnotes, proof that writing was not a solitary project, and that she identified with other poets, “with a tradition or knowable community.” [20]

She never seems timid about her vocation; she addresses publishers, correspondents and friends as a woman writer, and with a degree of confidence that is, at the very least, an impressive attempt to confront whatever anxieties lurked under the surface. Mary Ann ’s texts verify many feminist assumptions of the nineteenth century poetess, but some of her work challenges these concepts. This in itself is a good reason for reading her.

References and further reading

She was a poetess : the world of Mary Ann Allingham 1820-1836

by Niamh Hamill PhD

Allingham, Hugh. Ballyshannon, Its History and Antiquities with Some Account of the the Surrounding Neighbourhood. Ballyshannon: Donegal Democrat Ltd, 1937.

Allingham, William. William Allingham: A Diary. London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd, 1907

Blain, Virginia. “Women Poets and the Challenge of Genre.” In Women and Literature in Britain 1800-1900, 162-188. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001

Bohls, Elizabeth A. Women Travel Writers and the Language of Aesthetics, 1716-1818. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Campbell, Matthew. Irish Poetry under the Union, 1801-1924. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Gilbert, Sandra M.and Gubar, Susan. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).

Haberstroh, Patricia Boyle. Opening the Field: Irish Women: Texts and Contexts. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2007.

Hagan, Linda M. “The Ulster-Scots and the ‘Greening’ of Ireland: A PrecariousBelonging?” In Affecting Irishness: Negotiating Cultural Identity within and Beyond the Nation, 2, 71-88. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009.

Hill, M and D Hempton. “Women and Protestant Minorities in Eighteenth-Century Ireland.” In Women in Early Modern Ireland, 160-178. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991.

Homans, Margaret Womn Writers and Poetic Identity Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Horner, Avril and Sue Zlosnik. Landscapes of Desire: Metaphors in Modern Women’s Fiction. London: Harvester, 1990.

Jackson, Virginia. “The Poet as Poetess.” In The Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth Century American Poetry, 54-75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Levin, Susan M. Dorothy Wordsworth and Romanticism. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2009.

Romanticism and Feminism, Edited by Anne K. Mellor. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Sage, Lorna, Germaine Greer and Elaine Showalter. The Cambridge Guide to Women’s Writing in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Vincent, Patrick H. The Romantic Poetess: European Culture, Politics, and Gender, 1820-1840 (Lebanon: University of New Hampshire, 2004),

Niamh Hamill

Dr. Niamh Hamill is a lecturer in Irish history and literature. In 2015, her work She was a poetess- the world of Mary Ann Allingham 1820-1836 was awarded the Drew University prize for best interdisciplinary doctoral dissertation. Niamh is the Director of the Institute of Study Abroad Ireland, an organization that provides educational study trips for American schools, colleges and universities in Donegal. Niamh is also the director of the Drew University Transatlantic Connections Conference, which takes place in Bundoran each January. Her work is focused on promoting the history and culture of Donegal to a global audience.

If you would like to feature your research on our blog please email Dr Deirdre Flynn.

Notes:

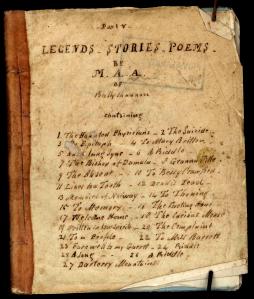

[1] Forward to Songbook V.

[2] Elizabeth A. Bohls, Women Travel Writers and the Language of Aesthetics, 1716-1818 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 3.

[3] Ibid, 18.

[4] Margaret Homans, Women Writers and Poetic Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 71-73

[5] Margaret Crawford’s wedding, for example, ‘Verses to Margaret Crawford IV3).

[6] See Homans, 73.

[7] Susan M. Levin, Dorothy Wordsworth and Romanticism (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2009), 9.

[8] Stuart Curran draws attention to the association of the term ‘poetess’ with indoor space and domestic preoccupation. British poet Alfred Lord Tennyson was criticised for his ‘feminine’ tendencies; – “Tennyson, we cannot live in art”. Curran explains, “He was, in essence, demanding that his friend forsake the female space of enclosure, fantasy and long-past ages for a contemporary and necessarily masculine outdoors.” Stuart Curran, “Women Readers, Woman Writers,” in The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism, ed. Stuart Curran(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 182.

[9] There are few comparisons of political writing like this by early nineteenth century women. Helen Maria Williams (c1761-1827) writes about the French Revolution in A narrative of the Events Which have Taken Place in France (1815). See Nineteenth Century Women Poets (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 74.

[10] Bohls, 21.

[11] Patricia Howell Michaelson, Speaking Volumes : Women, Reading, and Speech in the Age of Austen (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2002), 29.

[12] Part IV LEGENDS – STORIES – POEMS no.24

[13] Karen O’Brien writes that the work of Walter Scott, among others, nurtured an idea of womanly affinity with tradition and cultural heritage. Karen O’Brien, Women and Enlightenment in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 203.

[14] See Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic : The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 48-50.

[15] Hugh O’ Donnell IV22, Grace O’ Malley (Granna Uille) V8, Fin Mc Cool IV1.

[16] Mary Ann Allingham, ‘The Days that are gone’ published in The Ballyshannon Herald, 1831.

[17] From ‘An Excursion to Donegal’, Dublin Family Magazine, September 1829.

[18] Terence Brown quoted in Frank Ferguson, “The Third Character: The Articulation of Scottish Identities in Two Irish Writers,” in Across the Water: Ireland and Scotland in the Nineteenth Centrury, ed. Frank Ferguson and James McConnell (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2010), 65.

[19] Andrew Carpenter notes that pamphlets and broad sheets of the 1700s also often used the Irish ‘amhrán’ or song meter “which meant that they would sometimes choose a word more for its sound or metrical value than for its meaning.” Andrew Carpenter, “Poetry in English, 1690-1800,” in The Cambridge History of Irish Literature, ed. Margaret Kelleher and Philip O’ Leary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 305.

[20] Patrick H. Vincent, The Romantic Poetess: European Culture, Politics, and Gender, 1820-1840 (Lebanon: University of New Hampshire, 2004), 191.