Research Pioneers 1: John Wilson Foster

Research Pioneers in Irish Women’s Writing: An Interview Series

Introduction

Since the 1990s, scholarship on Irish women’s writing has made some significant strides in recovering forgotten authors and texts. Thanks to pioneering work by researchers such as John Wilson Foster, Patricia Coughlan, Heidi Hansson, Margaret Kelleher and James H. Murphy, we have begun to see developments that conceptualise and offer new frameworks for researching and understanding Irish women’s writing of the period between 1880 and 1920.

Evidence of the surge in interest in Irish women’s writing came recently during a conference staged by the International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures, which celebrated its 50th anniversary at Trinity College Dublin in July 2019. This conference brought together a global community of scholars to reflect on the topic of ‘Critical Ground’. During thought-provoking roundtable discussions such as “Displacing the Canon” and “Feminist Wonder? Twenty-First Century Interventions in Irish Studies”, important questions were raised about the need to diversify the teaching syllabus, revisit categories such as the ‘Irish writer’ and what we might mean by it, and opening out the field of Irish Studies to include transdisciplinary, transnational and multi-lingual approaches. With digitisation projects of archival materials on the rise, access to primary resources and previously untapped critical texts are increasingly available to enable new directions in the scholarship of Irish women’s writing.

Yet where we seem to take ten steps forward, there is all too often a push-back. A telling example of this came in 2017, when the Cambridge Companion to Irish Poets, edited by Gerald Dawe, caused controversy for its appalling gender imbalance by including the work of only four females among a total of thirty poets overall. Most notable perhaps was the fact that all the females whose poems were selected for publication in the Cambridge Companion were born in the twentieth century.

It is thus important to engage in an ongoing process of reflecting on the historiography of Irish women’s writing and revisiting the motivations for recovering women’s voices. The continued relative scarcity of attention to women’s literary works in textbooks, scholarly research and literary anthologies invites us to consider which questions we are still grappling with and where new avenues of research have or might yet be opened up for scholarship.

Looking back at the research and recovery efforts of those who have gone before is an imperative process in continuing to respond to the need for greater visibility of and accessibility to Irish women’s writing of the 1880 to 1920 period. This is precisely the reason that, in this series of interviews, we are asking pioneering scholars to share the challenges and opportunities they saw and continue to see in this lively research field.

Anna Pilz & Whitney Standlee

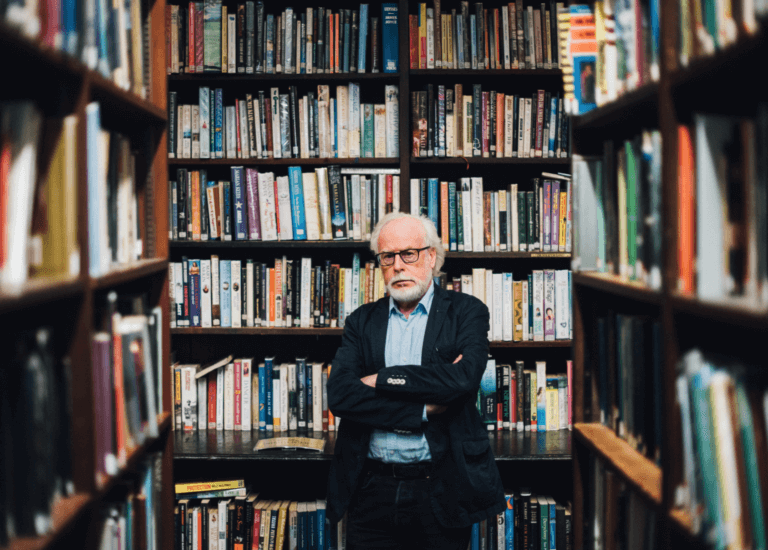

John Wilson Foster

John Wilson Foster’s early works Forces and Themes in Ulster Fiction (1974) and Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival (1987) acted to challenge the scope and content of Irish literary research, while his 2008 study Irish Novels 1890–1940: New Bearings in Culture and Fiction unearthed and reclaimed a number of critically neglected texts by female authors. Much of his corpus of research has, in fact, proved invaluable to the process of focusing critical attention on women’s contribution to the shaping of the literary landscape of Ireland. We ask him here about these research and recovery processes, and his hopes for the future of academic exploration into Irish women’s writing.

You have worked over the course of your career to identify and fill gaps in Irish literary research. What drew you to the study of overlooked texts?

I have not thought about this until you asked this question, but my scholarly work seems to have been impelled by two motives: to look beyond given or orthodox explanatory narratives, be they historical or literary-critical, and investigate what lies beyond and hasn’t been accounted for; and to bring diffuse material (multiple texts, authors, events) into some order, assuming that the order or pattern is somehow intrinsic to the material. I see now that the three critical works you mention were so motivated, as were my editing work in Irish natural history (Nature in Ireland, 1997) and my exploring of what I called The Titanic Complex (1997). I now realize that these two impulses were encouraged early on by my supervisor and mentor at Queen’s University, Philip Hobsbaum, critic and poet, who valued originality, scope, and scepticism. But the origin of it all might have been my unfulfilled boyhood ambition to be a serious field ornithologist, always tuned to the rare, unusual, or overlooked.

How did you locate and access the materials for your earliest research?

How different literary research was before the internet, before Google and Amazon! I always give a simple example. While reviewing one of Seamus Heaney’s volumes of poetry in my Vancouver townhouse, I came across an unfamiliar title of what I assumed rightly was the title of a song or tune, “The Rose of Mooncoin”. Before the internet I would have travelled to the University of British Columbia library, rifled through the subject catalogue hoping I would find a card for a book of Irish songs, hoping the book was not out on loan, and hoping the book reprinted the words of “The Rose of Mooncoin”. As it was, within a minute I was reading the lyrics of the song and listening to its tune on my laptop. Before that, I was entirely reliant on university and public libraries and on leads and references from friends and colleagues: I’m sure that a good few of the authors and works I discussed in Forces and Themes in Ulster Fiction (1974) were from tips from another mentor and friend, the writer Benedict Kiely, during the year we were both in Eugene, Oregon.

Can you recall a particular ‘Eureka moment’ from the archives?

A recent moment that might qualify as a ‘Eureka’ moment was when, being starved of biographical information on the non-literary subject of a book I’m now finishing up, I Googled a writer who had once written, but not published, on the businessman in question and was led to the Library of Congress. There in the writer’s immense archive I found that box 155 was named for my subject. I shouted Bingo! – the equivalent , I suppose, of Eureka! But normally ‘Eureka moment’ is too graphic a phrase. Still, when I looked up an Irish woman writer whose name was utterly new to me, Hannah Lynch, sent off for her books on inter-library loan, read her, and realised she was the real thing, that was an extended low-intensity ‘Eureka moment’.

Your seminal study Irish Novels 1890–1940 includes significantly more works written by female authors than by males. What do you think accounts for this imbalance?

The imbalance is easily explained. In Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival (1987) I was critically surveying ‘serious’ fictions (by mostly male Irish writers), that had been neglected as a coherent body of work because, I suspected, the contemporary Irish novel ran counter to the prevailing primary and secondary narrative of Irish Revival literature. (Hence in the secondary narrative the convenient untruth that the Irish were poets and playwrights but not novelists in the accepted sense.) This body of work qualified or contradicted the (highly nationalistic as well as male) literary and quasi-political value-system relayed by the orthodox narrative. However, in that book I had ignorantly and prejudicially turned my back on the very diverse and rich body of popular Irish fiction of the period. (I mean by ‘popular’ that the fiction sold well and had a broad readership, not that it was never ‘serious’.) Some of the women writers were prodigiously productive. When I later got around to investigating, I discovered that Irish women writers more or less owned popular Irish fiction of the Revival period and that it, too, contradicted the cultural nationalism and restricted canon of the Irish Literary Revival that took up all the critical oxygen. Many of the women writers lived or travelled outside Ireland and often set their fictions abroad. I was astonished to find so many highly readable, occasionally top-class, mostly unknown let alone neglected, Irish women novelists. Something big and new swam into my ken.

If you could pick a single Irish woman writer of the period 1880-1920 to interview, who would it be and why?

That is a hard question. The candidates would include B.M. Croker (about her life in India and Burma), and Kathleen Coyle, Beatrice Grimshaw, Ella MacMahon and Katherine Thurston for their unorthodox and slightly mysterious lives. Helen Waddell would be too dauntingly erudite for me. But my final choice would be Hannah Lynch, superbly unorthodox, intelligent, and also rather mysterious though I understand a biography has just appeared.

Some of the texts you have focused a good deal of attention on, such as M. E. Francis’s Dark Rosaleen and Pamela Hinkson’s The Ladies’ Road, have yet to generate significant critical interest. Do you feel that these works merit further academic study?

I was interested in Dark Rosaleen for what we might call its cultural geography and anthropology, by turns realistic and lurid. I personally don’t need to return to it now that I think I’ve decoded its national and sectarian allegory. However, I found Hinkson’s The Ladies’ Road a much more sophisticated and finely tuned work that occupies a later generation of thinking and feeling. I think it worthy of sustained aesthetic as well as social interest. But the Great War about which she writes has not been entirely rehabilitated as a legitimate Irish theme. You remember that Yeats poo-poohed Sean O’Casey’s choice of it as a dramatic subject.

What, in your view, are the most important issues and most promising avenues for future research in Irish women’s writing?

Well, we’re still in the recovery phase of Irish women’s writing of the past. I hope that where fiction is concerned Irish Novels 1890-1940 identifies neglected writers of that half century (straddling Irish independence and the Literary Revival) who have still to be read and discussed uniquely outside my survey. That would add the rich essential details in a remapping of Irish fiction of the period. But there is also the succeeding eighty years. And there seems to be an acceleration at work. It’s clear that Irish women’s writing is in an extraordinarily healthy state, in terms of accomplishment, prolificness, and sales. It seems, indeed, to be finding the new paths. Those paths will have to be charted by the critics. They include innovative formal experimentation which has not been traditionally a feature of Irish female fiction, whose strength has been intimate detail and the privileging of the empirical, the personal, romantic, and social over the political or culturally political. Hence not easily amenable to a male interpretation that is preoccupied with identifying and measuring Irishness. I suppose I should admit (as someone who is both British and Irish) to my own master-narrative bolstered by my reading of the Irish women writers: that Irish experience has always been intimately entwined with British (and European) experience and that an excessively nationalist reading of Irish life and history is reductive and unhelpful. In any case, the new fiction will set the critical agenda. Before long there will be fictions generated by the female (as well as male) Irish immigrant experiences which will add multicultural dimensions to criticism at present unforeseeable.

To reference this blog:

Harvard style:

Foster, John Wilson (2019), ‘Research Pioneers’, Interviewed by Anna Pilz and Whitney Standlee for Irish Women’s Writing (1880-1920) Network, (October, 2019). Available at: https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/2019/10/07/research-pioneers-1-john-wilson-foster/ (Accessed: Date)