Numbers, Narratives, and New Perspectives

Inspirations from the ‘Irish Women Playwrights and Theatremakers’ Conference

by Dr Anna Pilz (UCC)

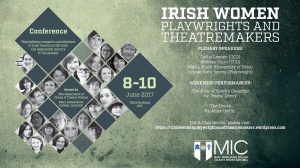

There was a palpable sense of historical significance in the air when activists, theatre practitioners as well as national and international scholars descended upon the Drama & Theatre Studies Department at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick for the ‘Irish Women Playwrights and Theatremakers’ (8-10 June) conference.

There was a palpable sense of historical significance in the air when activists, theatre practitioners as well as national and international scholars descended upon the Drama & Theatre Studies Department at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick for the ‘Irish Women Playwrights and Theatremakers’ (8-10 June) conference.

The three-day event was filled with stimulating papers, compelling plenaries, evocative performances, and exchanges. Appropriately and importantly, the conference had kicked off only a day after the launch of the report Gender Counts: An Analysis of Gender in Irish Theatre 2006-2015 thanks to the magnificent and relentless work of the research committee of the #WakingTheFeminists movement.

Gender Counts confirmed and revealed in black and white numbers the marginalisation of women in Irish theatre between 2006 and 2015. While the numbers speak loud and clear, the conference offered an excellent platform to enmesh quantitative analysis with qualitative research and personal experiences. In many ways, it was not only a moment to voice frustrations and call for change, but it was also a three-day recognition of women’s central contribution to Irish theatre, both at home and abroad.

Focusing on the top ten theatre organisations that receive Arts Council funding, Gender Counts highlights the astoundingly low percentage of female playwrights; only 28% of authors employed between 2006 and 2015 were women¹. How many, I wondered, Irish female playwrights were there between 1880 and 1910? Maud Gonne, Constance Markievicz, Eva Gore-Booth, Alice Milligan, Lady Gregory, and Winifred Letts come to mind. But are those representative? In 1892, the Daily Graphic noted that Irish fiction, at that moment, was ‘practically in the hands of Irish women’². Where, however, were Irish women playwrights? The 28% mentioned above only account for those who made it to the stage; but what about the percentage of plays written that were never (or rarely) encountered by a theatre audience?

There was a recognisable gap between Dr David Clare’s opening paper on Frances Sheridan, Elizabeth Griffith, Mary Balfour, and Maria Edgeworth in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and Lady Gregory’s drama in the early twentieth century. Clare productively pointed to the loss of texts by Irish women playwrights in the earlier period: texts that either never made it to publication or texts that have suffered from a subsequent neglect of scholarly editions such as the plays by Edgeworth. The identification and retrieval of such texts is important to gain a fuller understanding of women’s contribution to the dramatic tradition. And it also called to mind discussions at the inaugural conference of the ‘Irish Women Writers 1880-1910 Network’ in November 2016 where one potential initiative of the network could be in bringing works back into print via inclusion in Tramp Press’s Recovered Voices Series.

For scholarship on women’s writing, the plenaries by Dr Cathy Leeney and Dr Melissa Sihra were particularly thought-provoking in that they argued respectively for “new ways of seeing” and a “tilting of the lens” to bring to light new insights and important correctives to established narratives of literary history. Both plenaries equally stressed the importance of linking past and present, to consider points of connection and disconnection.

Leeney’s excellent plenary on “Waking up to Theatrical Aesthetics: Women’s Way of Looking”, highlighted the value of historical research in that it is an act of ‘recovery of the roots of self’; historical research assists in challenging and rejecting established narratives. Such a rejection of established narratives was most provocatively demonstrated in Sihra’s magnificent and inspired plenary titled “Beyond Token Women: Towards a Matriarchal Lineage from Lady Gregory to Marina Carr” which rendered Gregory not simply co-founder and playwright, but precursor to Synge, Beckett, Murphy and Carr in dramatic craft, language, and themes. Such levelling of the field helpfully disrupts Irish theatre history as we know it and as we find it reiterated in survey texts such as The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Theatre.

A personal highlight for me, Sihra’s historically grounded argument was poignant in many ways. For one thing, I myself had engaged in quantitative research by tallying up performances of Gregory’s plays between the opening of the Abbey in 1904 to the playwright’s death in 1932, and for the period from 1933 to 2011. Comparing the figures to performances of plays by her co-directors of the early Abbey, W.B. Yeats and J.M. Synge post Gregory’s death, I was counting from high visibility to invisibility. Yet such harsh numbers present only part of a picture that requires further unpacking. And in terms of literary history, that unpacking often requires diligent journeys into archives.

In fact, the wealth of archival research presented in numerous papers at the conference pointed to the difficulties of researching women’s lives and writings that requires creativity in sources. After all, it is not always easy to trace women within archival collections and more often than not is necessitated by a compilation of sources from birth, marriage and death certificates, letters, diaries, periodicals and newspapers. Yet hunting archival collections pays off; there was a moment of gasping astonishment and admiration for Dr Ciara O’Dowd’s scholarship on the Abbey actress and later artistic director Ria Mooney. O’Dowd discovered and revealed the effectiveness of fresh perspectives which, in this instance, resulted in a re-framing of Mooney’s work. While Mooney as a woman in Irish theatre history is associated, primarily, with the role of the prostitute Rosie Redmond in Seán O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars, as an Irish woman in a more globalized theatre world, Rooney is lauded as Assistant Director to the acclaimed Eva Le Galienne on Broadway in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

This leads to one of the over-arching threads across papers and across periods. I was struck by the repeated references to the success of Irish women playwrights on the international stage while facing rejection at home. This would seem to suggest two very different strands of narrative: one concerning women and Irish theatre which is characterised by hardship, marginalisation, and depreciation; the other about Irish women and theatre which appears to point to a rather different narrative that is filled with cultural exchange, opportunity, and success. These two narrative frameworks – women and Irish theatre versus Irish women and theatre – signal the importance of framing and point of view. Of course, this is somewhat oversimplifying a complex relationship. But to an extent, it is a question of scale and placing (Irish) women writers – of theatre or otherwise – within wider European and transnational contexts. Again, Gregory is a case in point. In a fruitful discussion with PhD candidate Justine Nakase (NUI Galway), who directed Gregory’s play Grania in 2016 (a play that was never staged during Gregory’s life-time³), it emerged that perceptions of Gregory’s stuffiness might be due to some kind of cultural blindness and national baggage that international theatre practitioners are free of. For women’s literary history more broadly, it would seem that transnational perspectives have much to offer.

If you have any suggestions for the blog or would like to submit a post email Dr Deirdre Flynn

- Brenda Donohue, Ciara O’Dowd, Tanya Dean, Ciara Murphy, Kathleen Cawley, Kate Harris, Gender Counts: An Analysis of Gender in Irish Theatre 2006-2015 (2017) p. 6.

- ‘Irish Fiction’, Daily Graphic (5 October 1891), quoted in Gifford Lewis (ed.), The Selected Letters of Somerville and Ross (London: Faber & Faber, 1989), p. 178.

- Nakase’s production of Gregory’s Grania premiered on 28 January 2016 to launch the Galway-based #wakingthefeministswest season.