Re-examining Wilde in The Woman’s World

Eleanor Fitzsimons

How to cite: Fitzsimons, E. (2024) ‘Re-examining Wilde in The Woman’s World’, IWWN Blog, date of posted entry, Available at https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/blog/ (Accessed date)

‘Society began to take Oscar Wilde seriously when he became editor of the Woman’s World.’

Anna de Brémont in Oscar Wilde and His Mother (1911)[1]

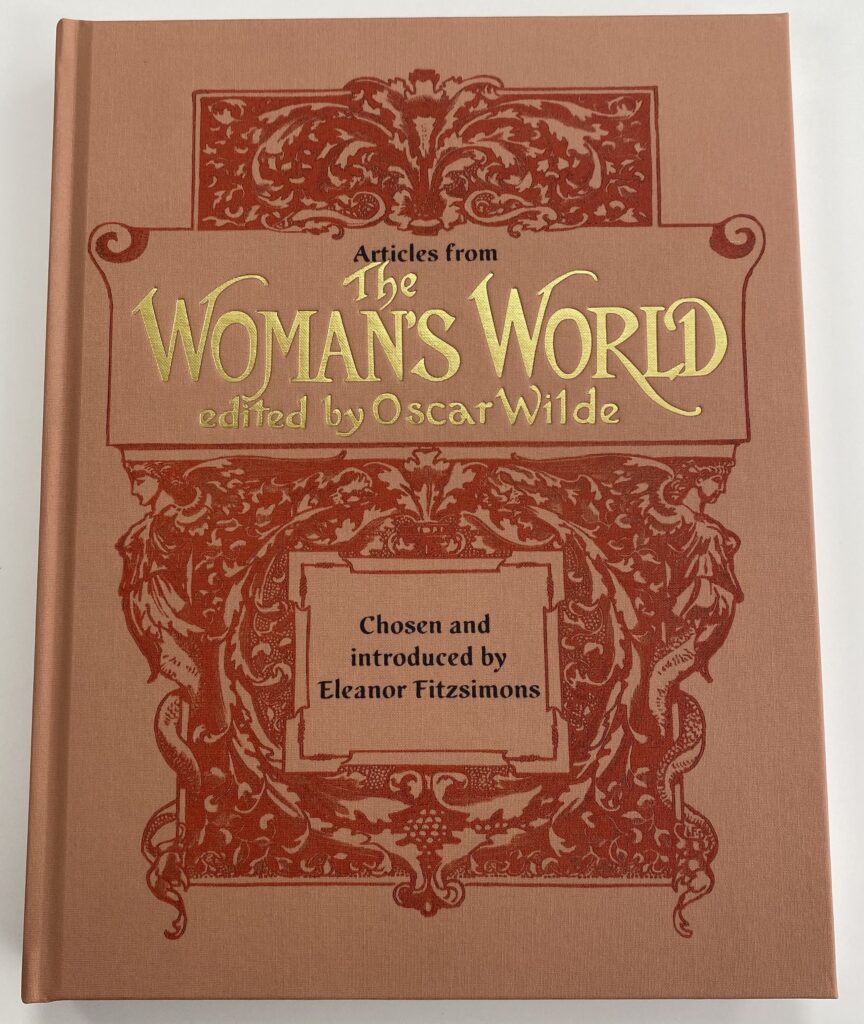

In 2023, the Oscar Wilde Society, of which I am an honorary patron, commissioned me to compile Selected Articles from The Woman’s World, a project made possible through the generosity of Mrs. Joan Winchell, who also supported the publication of Constance Wilde’s Autograph Book 1886 – 1896, edited by society member Dr Devon Cox. My project continues an ongoing process of retrieving the lesser-known writings of Wilde and his circle. While digitised issues of The Woman’s World are available online, this project allowed me to provide a comprehensive account of Wilde’s time as editor, to add contextualising notes for a modern readership, and, most importantly, to write biographical profiles for many of Wilde’s contributors, all of them deserving of greater attention. Thirty articles were selected to represent the breadth of topics Wilde’s contributors tackled. Several showcase the distinctive artwork that influenced the design of his beautiful, aesthetic books; Charles Ricketts and Walter Crane, among others, produced illustrations for The Woman’s World before collaborating with Wilde.

Recent scholarship, by Laurel Brake, Petra Clark, Loretta Clayton, Anya Clayworth, Stephanie Green, Sandra F. Siegal and others, has revealed that early biographers of Wilde underplayed the importance of his time as editor of The Woman’s World, which is far more significant than was believed previously. Many, Richard Ellman among them, relied too heavily on accounts left by Arthur Fish, Wilde’s sub-editor during the latter part of his tenure, and concluded that he was attracted by a regular salary but lost interest within months. New research from Rob Marland and Wolfgang Maier-Sigrist[2] has revealed that Fish was appointed far later than previously thought and therefore not privy to the highly productive early months of Wilde’s tenure. From April 1887, he took on the radical reform of The Lady’s World, a magazine he considered ‘too feminine and not sufficiently womanly’, [3] transforming it into The Woman’s World, ‘the recognised organ for the expression of women’s opinions on all subjects of literature, art, and modern life’.[4] This was the only salaried position he ever accepted. His disenchantment was driven largely by the opposition he encountered.

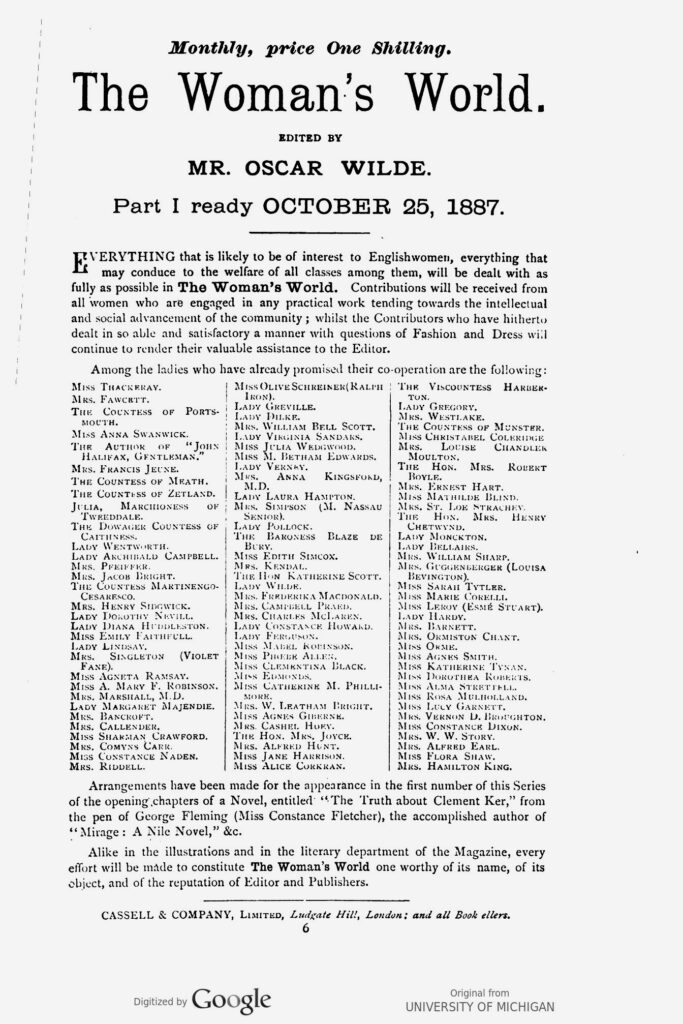

Wilde was in his early thirties, married with two young children, and earning an unreliable income as a lecturer and literary critic when he received a letter from Thomas Wemyss Reid, General Manager of Cassell and Company, Ltd., in April 1887, asking if he might consider editing The Lady’s World. This was the high-end monthly magazine Cassell had launched in October 1886 in a bid to profit from the emerging market for magazines targeted at women. Competition was fierce. In Women’s Magazines, 1693 – 1968, Cynthia Lesley White identifies forty-eight new titles targeted at women that appeared between 1880 and 1900 alone.[5] Pitched against The Ladies’ Pictorial (1881-1921), The Lady (founded in 1885) and others, The Lady’s World was struggling to survive. Wilde’s attractiveness as editor likely rested on his relative fame, his association with the burgeoning aesthetic movement, and his forthright opinions on dress, which he had expressed in articles such as ‘The Relation of Dress to Art’ (Pall Mall Gazette, 28 February 1885) and ‘The Philosophy of Dress’ (New York Daily Tribune, 19 April 1885). The Cassell prospectus for the first issue of their relaunched magazine under Wilde’s editorship makes it clear that their modest plan was for him to build on the ‘recognised and unique position’ of The Lady’s World and attract ‘an even larger circle of readers than hitherto’.[6] Sos Eltis characterizes the contents of The Lady’s World as:

Regular monthly features were ‘Fashionable Marriages’, ‘Society Pleasures’, ‘With Needle and Thread: The Work of Today’, ‘Five O’Clock Tea’ (an account of the latest fashionable tea-parties and receptions), and ‘Pastimes for Ladies’, of which typical examples were shell- and pebble-painting, mirror-painting, or, for the more adventurous, sleighing.[7]

Reid was likely surprised by the length and specificity of Wilde’s response, which began: ‘I have read very carefully the numbers of the Lady’s World you kindly sent me, and would be very happy to join with you in the work of editing and to some extent reconstructing it.’[8] Although his first issue was not scheduled to appear until November 1887, Wilde asked that his salary be backdated to 1 May, arguing: ‘It is absolutely necessary to start at once, and I have already devoted a great deal of time to devising the scheme, and having interviews with people of position and importance’.[9] His first confrontation with Cassell’s management was his insistence, in the face of considerable opposition, that the name be changed. Citing support from influential prospective contributors, among them novelist Anne Isabella, Lady Ritchie, eldest daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray, journalist Frances Parthenope Verney, whose sister was Florence Nightingale, and novelist and playwright Julia Constance Fletcher, who wrote bestselling novels as George Fleming, he argued, ‘the retention of the present name will be a serious bar to our success.’[10] His preferred title, The Woman’s World, suggested to him by novelist Dinah Craik, had the gravitas required for a magazine he planned to transform into ‘the organ of women of intellect, culture, and position.’[11] Stella Newton suggests that it paid tribute to the Woman’s World magazine of the late 1860s, which advocated political and legal rights for women.[12]

Wilde’s entry into this complex, crowded marketplace coincided with a society-wide evaluation of the quality of ‘womanliness’ and a consequent reassessment of what topics would interest women readers. Laurel Brake believes that The Woman’s World constructed women as ‘serious readers who want (and need) education and acculturation’.[13] Certainly, Wilde needed to attract a large emerging readership of more socially aware and artistically inclined middle-class women who had sufficient disposable income to spend on an expensive, at one-shilling, monthly magazine. He planned to take it far beyond the idealised notions of femininity, unhealthy preoccupations with restrictive fashion, and predominance of domesticity, household management and trivial society gossip that characterised competing magazines: characteristics that, according to Kay Boardman and Margaret Beetham, ‘combined to create a femininity of surface rather than depth, of appearance rather than moral management’.[14] Arthur Fish, who identified the ‘keynote’ of The Woman’s World as ‘the right of woman to equality of treatment with man’, recognised that the articles on ‘women’s work and their position in politics were far in advance of the thought of the day’.[15] Wilde’s passion for collaborating with marginalised, avant-garde women to help them address their concerns, is apparent throughout, as is his determination to subvert the strict, gendered orthodoxy of Victorian life.

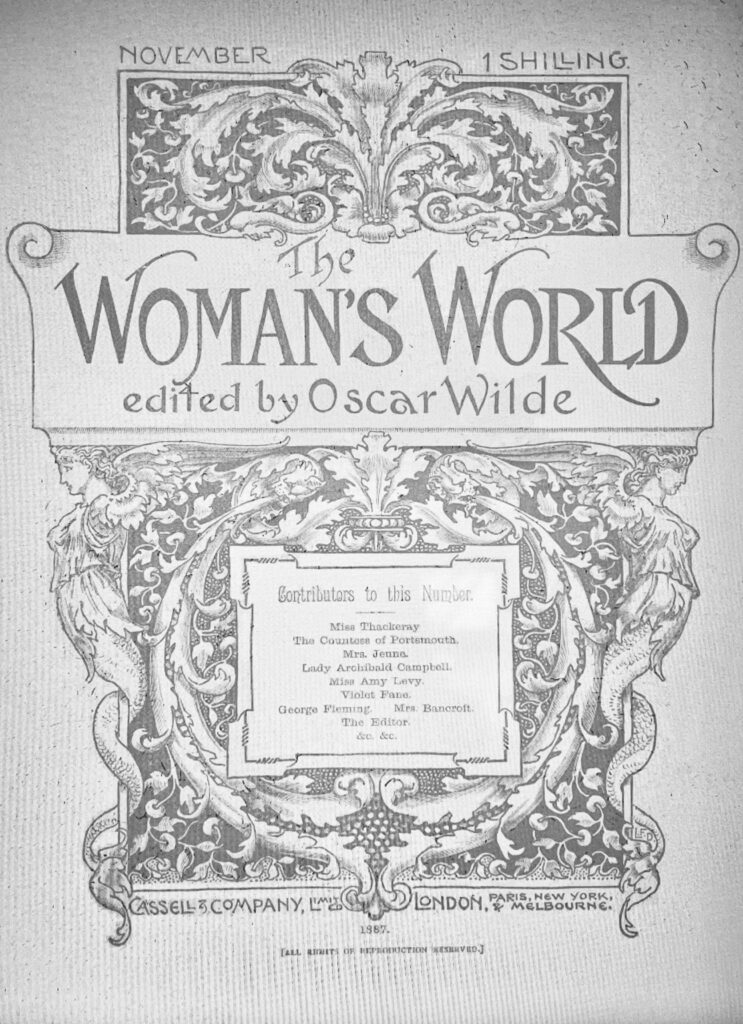

With the new title came a new, aesthetic cover with the declaration ‘edited by Oscar Wilde’, highly unusual at this time and unique for Cassell. The box below contained the names of several high-profile contributors. The identification of each contributor at the end of their article by forename and surname, with no mention of title or marital status, followed the convention used by professional writers, who were generally men. This afforded women contributors equal status with men, an opportunity to build their professional profile, and a platform to create awareness for the causes they championed. Wilde was well-connected and had little difficulty attracting contributors, particularly after the first issue appeared. He tapped into the network established by his celebrated mother. As family friend and Wilde biographer Anna de Brémont recalled:

There was a flutter in the boudoirs of Mayfair and Belgravia…Lady Wilde’s Saturdays were thronged. Ladies of high degree and ladies of no degree – poets and painters, artists and art critics, writers, and scribblers, all eager to attain a place in the pages of the new magazine.[16]

Yet, he was careful in his choice of contributor. Months before his first issue was published Wilde was expending considerable time and effort on attracting the women, and few men, he had identified as best suited to the ethos he wished to cultivate. He leveraged his connection to leading society hostess and social reformer, Mary Jeune, Baroness St Helier, to recruit two of Queen Victoria’s daughters, allowing Cassell to advertise that ‘H.R.H. Princess Christian’ would be one of their contributors. Rather than write something trivial, Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, who was President of the Royal British Nurses’ Association, and a founder member of the Red Cross, wrote the informed and interesting ‘Nursing as a Profession for Women’ (April 1888) under her given name, ‘Helena’. Wilde employed clever flattery to secure three articles from German noblewoman Elizabeth of Wied, first Queen of Romania, who wrote as ‘Carmen Sylva’. He asked Emma B. Mawer, who had acted as an intermediary between the queen and Florence Nightingale when the latter established a nursing society in Romania in 1877, to write a flattering profile, ‘“Carmen Sylva,” the Poet-Queen’ (April 1888). Mawer then translated the queen’s articles from German to English. Wilde’s employers at Cassell must have been delighted when the Derby Mercury enthused ‘Mr. Oscar Wilde, as editor of the Woman’s World, has excelled himself this month [January 1889] in being able to number a queen among his contributors.’[17] He commissioned new fiction and poetry from radical emerging voices, but he was careful to feature stories by society women too, among them Julia, Lady Jersey, eldest daughter of Sir Robert Peel, founder of the Metropolitan Police Force, who wrote ‘Sybil’s Dilemma’ (April 1888), and Irishwoman Lady Virginia Sandars, who wrote ‘Love’s Absolution’ (June 1888). Sandars sat on the management board of Madame Devey’s Company, an organisation founded by women to protect women workers in the West End fashion industry. Their recognition that ‘every London season was inaugurated by the death of one or more victims, who had succumbed under the terrible labours to which they were subjected by the caprice of fashion’ chimed with Wilde’s interest in dress reform.[18] He attracted celebrity contributors too, among them popular novelist Marie Corelli, who outsold her peers, male and female, and gave him ‘Shakespeare’s Mother’ (June 1889), and the flamboyant Ouida, who gave him four brilliant essays: ‘Apropos of a Dinner’ (March 1888), ‘The Streets of London’ (September 1888), ‘War’ (February 1889), and ‘Fieldwork for Women’ (May 1889), the last of which she illustrated with her own oil paintings.

Recruiting the forthright, progressive women to whom he was not connected socially – pioneers in the trade union movement, higher education, and the professions – and steering them towards endorsing the radical social change he wanted to promote in the pages of The Woman’s World was more of a challenge for Wilde. He succeeded by writing a series of carefully crafted, speculative letters exemplified by the one received by philosopher, writer, trade union activist and feminist Edith Simcox during the summer of 1887. Assuming she was aware of The Lady’s World, Wilde assured her that he had been asked to ‘reconstruct and edit’ it, adding ‘the lines I propose to follow are literary, artistic and social in the sense of dealing with the practical work now being done by women in England’.[19] He then listed contributors and articles he had already secured, tailored to appeal to Simcox specifically. He promised ‘the magazine will have no creed of its own, political, artistic, or theological’, and was careful to mention that ‘the honorarium for writers will be a pound a page’, a generous fee. While assuring her ‘the subject is of course for you to decide’, he steered her towards the classics. He flattered her, insisting that her name would be ‘of great value to the magazine’. Simcox was convinced. Her article, ‘Elementary School Teaching as a Profession’ appeared in October 1888. Wilde adjusted this letter according to his prospect and replicated it many times. In ‘Oscar Wilde as a Professional Writer’, Ian Small points out the significance of these letters in providing evidence of Wilde’s willingness to take on dull administrative work, to be ‘a scribe, patiently copying and slightly modifying a pattern letter’.[20]

Many of the articles Wilde commissioned or accepted campaigned for the greater involvement of women in paid work, professional life, and higher education. He told publisher Emily Faithfull, a member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women who had used her feminist publications English Woman’s Journal (1860 – 1864) and Victoria Magazine (1863 – 1881), to advocate for women to have a right to paid employment, that he was ‘having a series of articles on what women can earn, and how they can make a livelihood’.[21] He ended by assuring her, ‘but for a few women like yourself such a magazine would have been an impossibility’. Faithfull gave him ‘The Endowment of the Daughter’ (June 1888), in which she insisted that women had a right to earn an income and encouraged the teaching of a trade or a profession to girls to keep them out of poverty. Wilde was supportive of women’s involvement in publishing. In his first editorial in November 1887, he noted that ‘the remarkable intellectual progress’ he had observed during his lecture tour of America in 1882 was ‘very largely due to the efforts of American women, who edit many of the most powerful magazines and newspapers, take part in the discussion of every question of public interest, and exercise an important influence upon the growth and tendencies of literature and art’.[22] He was likely referring to Kate Field and Mrs. Frank Leslie, both of whom he knew well.

Wilde used his lengthy ‘Literary and Other Notes’, his only written contributions to The Woman’s World, published in the first five issues, and replaced, after a hiatus, by shorter book reviews, to reinforce this. In January 1888, he praised Emily Pfeiffer’s weighty Women and Work as ‘a most important contribution to the discussion of one of the great social problems of our day’. Commenting that the ‘extended activity of women is now an accomplished fact; its results are on trial’, he hailed Pfeiffer’s ‘excellent essays’ for outlining ‘the rational and scientific basis of the movement more clearly and more logically than any other treatise I have as yet seen’.[23] In March 1888, he drew attention to The Englishwoman’s Yearbook, which contained ‘a really extraordinary amount of useful information on every subject connected with woman’s work’, remarking:

In the census taken in 1831… no occupation whatever was specified as appertaining to women, except that of domestic service, but in the census of 1881 the number of occupations mentioned as followed by women is upwards of three hundred and thirty. The most popular occupations seem to be those of domestic service, school teaching, and dressmaking; the lowest number on the list are those of bankers, gardeners and persons engaged in scientific pursuits.[24]

A gem among the series of articles that explored specific professions is ‘Medicine as a Profession for Women’ (January 1888) by Dr Mary Marshall, one of the ‘Edinburgh seven’, whose dignified campaign in response to the refusal to allow them to graduate as medical doctors earned them national attention and many staunch supporters, prominent among them Charles Darwin.

Access to higher education for women, a lifelong passion Wilde shared with his mother, was a key focus of The Woman’s World under his editorship. In his review of Pfeiffer’s Women and Work, he had quoted Daniel Defoe, ‘what has the woman done to forfeit the privilege of being taught!’[25] In his editorial for December 1887, he highlighted examples of academic achievement as evidence of ‘how worthy women are of that higher culture and education which has been so tardily and, in some instances, so grudgingly granted to them’.[26] He commissioned articles from graduates and undergraduates of the new women’s colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, among them ‘The Oxford Ladies Colleges’ (November 1887) by ‘A Member of One of Them’ for his very first issue in November 1887, and ‘Life at Girton’ by ‘A Girtonian’ in the last issue that appeared under his editorship in October 1889. When asking his friend Helena Swanwick to write ‘The Evolution of Economics: Competition-Combination-Cooperation’ (February 1889), a topic not traditionally examined by women, he assured her, ‘I am very anxious that those who have had university training, like yourself, should have an organ through which they can express their views on life and things’.[27]

Wilde was a highly accomplished classical scholar. His essay ‘Greek Women’ (1876) demonstrated his passion for connecting his studies to women long before he edited The Woman’s World. Little wonder that, as Isobel Hurst notes, under his editorship, The Woman’s World ‘exemplified the popular dissemination of Hellenism through periodical culture’.[28] Yet he had his own take on this. He encouraged his contributors to interrogate gendered Victorian social norms by promoting the model of emancipated women as a continuous possibility from ancient times to their modern incarnations, the Girton girl and the New Woman writer. Among the articles in this series were ‘Woman and Democracy’ (June 1888), in which suffrage campaigner Julia Wedgwood examined woman’s natural aptitude for democracy throughout history; ‘Roman Woman at the Beginning of the Empire’ (September 1888), in which young Irish academic Anne Richardson characterised women as powerbrokers in the ancient world; and ‘A Pompeian Lady’ (October 1888), in which Edith Marget depicted the opulent life of a wealthy, leisured lady, a description that appealed to aesthetic tastes and sat comfortably alongside contemporary articles on fashion and home decoration. In ‘Greek Plays at the Universities’ (January 1888), J. E. Case, who wrote as ‘a graduate of Girton’, advocated for women students who were being discouraged from staging Greek drama. She had played Electra in an enterprising all-woman production at Girton College in November 1883, at a time when similar performances had been cancelled amid fears of impropriety.

A key article in the classical series is ‘The Pictures of Sappho’ (April 1888), the earliest published article by classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison, a founder of modern studies in ancient Greek religion and mythology and the first British woman to achieve the status of career academic. Wilde would surely have known her by reputation and they had much in common. A devotee of aestheticism, Harrison wore pre-Raphaelite dresses, decorated her college room with wallpaper designed by William Morris, favoured paintings by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and enjoyed the poetry of Algernon Charles Swinburne. She drew heavily on the iconography of Greek vases for her research on Athenian ritual and religion at a time when Aubrey Beardsley and Walter Crane were finding inspiration in the artistry of the Attic vase painters. She also wrote aesthetic books that reflected Ruskin’s vision of the improving power of art. They had a personal connection through a mutual friend, archaeologist and art historian Eugénie Sellers Strong (1860-1943). Wilde described Sellers as a ‘young Diana’ on account of her beauty, while Harrison thought her ‘the most beautiful woman in London’. Historian Mary Beard, who has written extensively about Harrison, suggests a strong romantic, possibly sexual relationship between the women, making Harrison one of several queer women Wilde interacted with and commissioned to write for The Woman’s World. He had included her name in the list of desired contributors he sent to Reid in April 1887.

Ordinary working women were not neglected by Wilde. Several articles, among them Faithfull’s ‘The Endowment of the Daughter’, already mentioned, drew attention to the poverty these women experienced, and proposed solutions that went far beyond the usual ineffectual charitable works. In ‘Something About Needlewomen’ (May 1888), trade unionist Clementina Black highlighted the plight of impoverished needlewomen unable to earn a living wage from piecework. In ‘The Poplin Weavers of Dublin’ (July 1888), one of several articles examining working conditions in Wilde’s native Ireland, Irish journalist Charlotte O’Conor-Eccles insisted that better education and training would improve the prospects of Dublin’s women weavers. In ‘The Knitters of the Rosses’, a beautifully written companion article, Irishwoman Dorothea Roberts described the establishment of a scheme to provide a regular income to women living in rural Donegal in Ireland. Lady Jeune, an accomplished writer in her own right, gave him two articles: ‘The Children of a Great City’ in two parts (November 1887 and April 1888), in which she campaigned for the alleviation of child poverty, and ‘Irish Industrial Art’ (January 1889), in which she paid tribute to the quality of the textile sector in Ireland and wrote knowledgeably about how the progress of Irish industry was hampered by the lack of infrastructure. Wilde reinforced this in his editorial by encouraging readers to buy more Irish lace, and warning ‘it rests largely with the ladies of England whether this beautiful art lives or dies’.

Discrimination experienced by women was a common theme. In ‘The Position of Women’ (November 1887), Eveline, Countess of Portsmouth welcomed amendments to marriage law designed to reform an institution that, in her view, ‘might and did very often represent to a wife a hopeless and bitter slavery’. In ‘The Fallacy of the Superiority of Man’ (December 1887), Laura McLaren demanded to know: ‘If women are inferior in any point, let the world hear the evidence on which they are to be condemned’. The defining issue of the era was the campaign for women’s suffrage. In May 1889, Wilde used his review of Darwinism and Politics as a vehicle to declare: ‘The cultivation of separate sorts of virtues and separate ideals of duty in men and women has led to the whole social fabric being weaker and unhealthier than it need be.’ At this key moment in the campaign, he published ‘Women’s Suffrage’ (November 1888), the transcript of a speech delivered by political activist Millicent Garrett Fawcett, in which she drew attention to the absurdity of denying women the right to vote. In January 1888, he published in full ‘On Women’s Work in Politics’, a campaign speech delivered by Lady Margaret Sandhurst during her controversial bid to be elected to the London City Council. Constance Wilde, a member of the Chelsea branch of the Women’s Liberal Association, was campaigning on Sandhurst’s behalf at the time. Although Sandhurst was successful, the courts upheld a challenge from the man she had defeated and declared her election invalid.

Conservative voices still found a place in The Woman’s World, although they sat uneasily alongside such radical opinions. Wilde demonstrated a genuine commitment to progressive women, but, on occasion, he allowed their views to be challenged. He invited folklorist, ethnographer, and traveller Lucy M. J. Garnett to refute Fawcett’s arguments for women’s suffrage in her turgid, unconvincing ‘Reasons for Opposing Woman Suffrage’ (April 1889). He also allowed her to write ‘The Fallacy of the Equality of Women’ (October 1888), a polemical refutation of Laura McLaren’s ‘The Fallacy of the Superiority of Men’ (December 1887), in which McLaren had contended that women were ‘jealously excluded’ by men from all spheres of life bar the domestic. It is possible that Wilde engineered such controversy deliberately to attract attention in the press and avoid the alienation of his more conservative readers. Perhaps this was part of a balancing act designed to keep his employer happy. He strove to be inclusive and told Alice Westlake, a prospective contributor, that the magazine would ‘have no political or artistic creed of its own – it will be merely the channel through which many streams will flow’.[29]

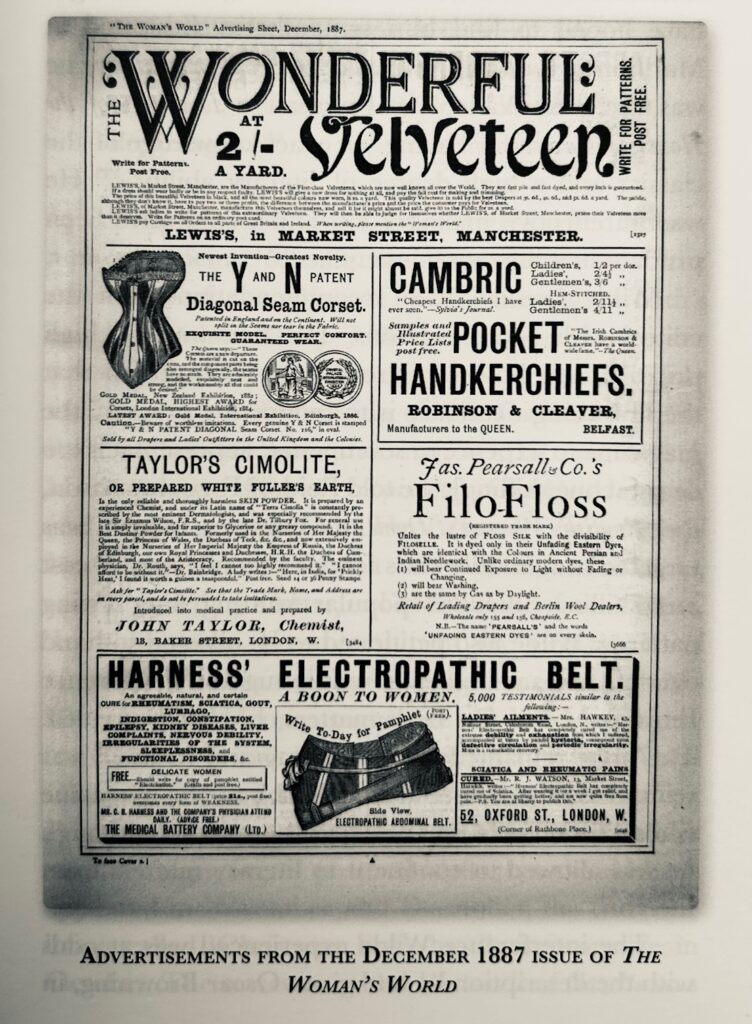

The inclusion of these more conservative articles rendered the magazine’s ideological stance quite incoherent. It was further undermined by advertisements for ‘glove fitting corsets’, ‘superior furniture cream’, ‘Letts Ladies’ Housekeeper Diaries’ and similar products carried in each issue of The Woman’s World but excluded from bound volumes. Such advertisements established it as a site of conformity to gendered, feminised roles such as beauty, homemaker, and mother, and jarred with its wider ethos and more aesthetic look. Nevertheless, The Woman’s World was generally regarded as liberal. Although the Englishwoman’s Review, the organ of the women’s suffrage movement, refrained from praising it overtly, it ran notices informing readers about the more progressive articles.

When it came to literature, Wilde was more surefooted. In October 1887, he told George Macmillan, a member of the publishing dynasty and an old friend from his student days, that he planned ‘to make literary criticism one of the features of the Woman’s World, and to give special prominence to books written by women’.[30] His own writing benefitted from exposure to these books. Many commentators recognise much of Ouida’s style in The Picture of Dorian Gray, his only novel, which he was contracted to write while editing The Woman’s World. His review of Faithful and Unfaithful by American novelist Margaret Lee in February 1889 is fascinating since it seems clear that her novel, which featured ‘a very noble and graciously Puritanic American girl, who is married at the age of eighteen to a man whom she insists on regarding as a hero’, influenced his plays A Woman of No Importance and An Ideal Husband, both of which contain similar themes.

Wilde sought out unconventional voices when commissioning poetry and fiction, a key feature of The Women’s World. He insisted that the best article in his first issue was ‘a story [‘The Recent Telepathic Occurrence at the British Museum’, sent unsolicited], one page long, by Amy Levy . . . a mere girl, but a girl of genius’.[31] Wilde championed Levy, an important Jewish author, commissioning stories, essays, and poetry from her, and lamenting her early death by suicide. He also brought South African-born feminist writer Olive Schreiner, who was living in poverty in London at the time, to the attention of his readers. When ‘Murder – Or Mercy?’, a story by New Woman writer Ella Hepworth Dixon, which contains elements of her celebrated New Woman novel The Story of a Modern Woman, appeared in August 1888 it was one of the first times her name had appeared in print. Dixon recalled receiving ‘a most flattering letter’ from Wilde in which he gave her story ‘unstinted praise which is so rare in Editors.’[32] He commissioned a second story, ‘A Literary Lover’ (October 1890) and two articles: ‘Women on Horseback’ (March 1889), in which she applauded the ‘semi-masculine and completely appropriate gear’ adopted by women who rode, and ‘On Cloaks’ (August 1889).

As a published poet who had adopted the form as a tribute to his poet mother, Wilde placed particular emphasis on poetry by women. This featured prominently in every issue and made up a good deal of his literary criticism. Reviewing The New Purgatory and Other Poems by social activist Elizabeth Rachel Chapman, he commented ‘we must not judge of woman’s poetic power by her achievements in days when education was denied to her, for where there is no faculty of expression no art is possible’.[33] Poetry written by women was ‘as a rule, more distinguished for strength than for beauty,’ he insisted, adding, ‘they seem to love to grapple with the big intellectual problems of modern life; science, philosophy and metaphysics form a large portion of their ordinary subject-matter’.[34] In his review of Women’s Voices, an anthology compiled by Elizabeth A. Sharp that included his mother’s work, he drew attention to Sharp’s ‘conviction that our women-poets had never been collectively represented with anything like adequate justice’, and her ambition to ‘convince many it is as possible to form an anthology of “pure poetry” from the writings of women as from those of men’. From this anthology, he singled out two New Woman poets who he later recruited as contributors: E. Nesbit, whose socialist poetry he admired and to whom he had acted as something of a mentor; and A. Mary F. Robinson, whom he knew socially, and whose influence can be detected in The Picture of Dorian Gray.[35]

Wilde promoted the work of other New Woman poets, among them interdisciplinary thinker Constance Naden, and Anglo-German poet and pioneering female aesthete Mathilde Blind. In December 1887, he reviewed Naden’s new collection A Modern Apostle; The Elixir of Life; The Story of Clarice, and other poems in which she expressed her engagement with the natural world, her observations about modern society, and the development of her philosophical ideas. He also published ‘Rest’ (March 1888), the last of her poems to appear before her untimely death in 1889. Naden, who was also a philosopher, a social activist and a key proponent of emancipation and education for women, coined the term ‘hylo-idealism’ to describe a philosophy she considered ‘highly relevant to aestheticism in that it was a way of linking matter and spirit in a godless universe’.[36] In 1891, Wilde renamed his story ‘The Canterville Ghost’, which had been published in The Court and Society Review in 1887, as ‘The Canterville Ghost: A Hylo-Idealistic Romance’, indicating his engagement with Naden’s philosophy. Dr Clare Stainthorp of Queen Mary, University of London and the British Association for Victorian Studies has written extensively about Naden. Wilde also accepted ‘Maria Bashkirtseff, the Russian Painter’ a beautifully illustrated article in two parts (June 1888 and August 1888) by Blind. This encouraged her to translate The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff, which Cassell published in 1890. In Mathilde Blind: Late-Victorian Culture and the Woman of Letters, James Diedrick writes that Blind’s translation ‘became a publishing sensation and intensified late-century debates concerning gender and sexual identity’.[37]

Although Wilde relegated the fashion pages to the back, he did not abandon The Lady’s World’s focus on fashion but shifted the emphasis radically. In his early exchange of letters with Reid he had pointed out that ‘the field of mere millinery and trimmings, is to some extent already occupied by such papers as the Queen and the Lady’s Pictorial,’ and insisted, ‘we should take a wider range, as well as a high standpoint, and deal not merely with what women wear, but what they think, and what they feel’.[38] One early sign of tension between Wilde and his employer was the restoration of an expanded fashion round-up to the middle pages from November 1888 onwards. In his Literary and Other Notes for December 1887, he offered what he described as his ‘exact position in the matter’:

Fashion is such an essential part of the mundus muliebris of our day, that it seems to me absolutely necessary that its growth, development, and phases should be duly chronicled… I must, however, protest against the idea that to chronicle the development of Fashion implies any approval of the particular forms that Fashion may adopt. [39]

His editorials and several of the articles he commissioned included commentary on the damaging effects of restrictive fashions on women’s lives. In his very first editorial, in November 1887, he predicted that ‘the dress of the two sexes will be assimilated, as similarity of costume always follows similarity of pursuits’. He acknowledged that this would require ‘women to invent a suitable costume, as their present style of dress is quite inappropriate to any kind of mechanical labour, and must be radically changed before they can compete with men upon their own ground’. The following month, he informed readers that the practice of restricting women through dress was nothing new: ‘From the sixteenth century to our own day there is hardly any form of torture that has not been inflicted on girls, and endured by women, in obedience to the dictates of an unreasonable and monstrous Fashion’. Insisting that it was ‘really only the idle classes who dress badly’, he made the case for the adoption of the more sensible dress ‘of the London milkwoman, of the Irish or Scottish fishwife, of the North-country factory girl’. Controversially for the time, he predicted that it was ‘more than probable, however, that the dress of the twentieth century will emphasise distinctions of occupation, not distinctions of sex.’[40]

Loretta Clayton, among other scholars, believes that Wilde’s influence on what she calls ‘aesthetic dress reform’ has been underestimated in scholarship.[41] He supplemented his aesthetic commentary with ideas propagated by the Rational Dress Society, of which his wife was a prominent member. In December 1887, he noted that the Rational Dress Society had sent a letter of remonstrance to the Empress of Japan who had been shopping for dresses in Paris and who, they believed, had resolved ‘to abandon Eastern for Western costume’.[42] Constance Wilde wrote two articles for The Woman’s World, ‘Muffs’ (February 1889) and ‘Children’s Dress in this Century’ (July 1888), in which she expressed her forthright opinions on rational dress. In ‘Mourning Clothes and Customs’ (June 1889), an excoriating article, Viscountess Harberton, founder of the Rational Dress Society and a close collaborator with Constance Wilde, condemned the onerous and expensive practice of obliging women to wear restrictive, expensive, and depressing clothing in response to a death.

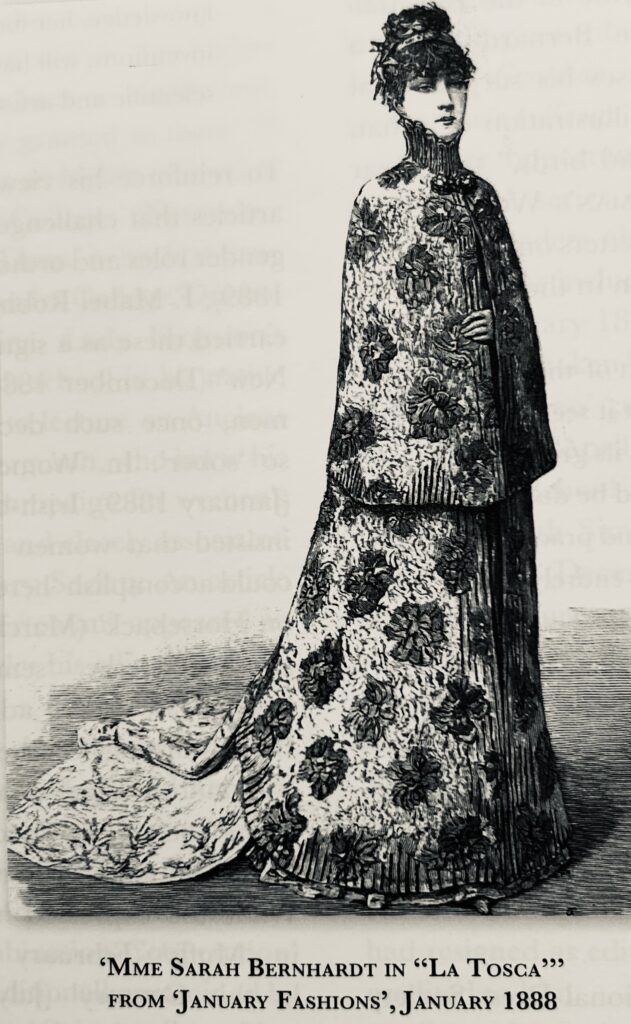

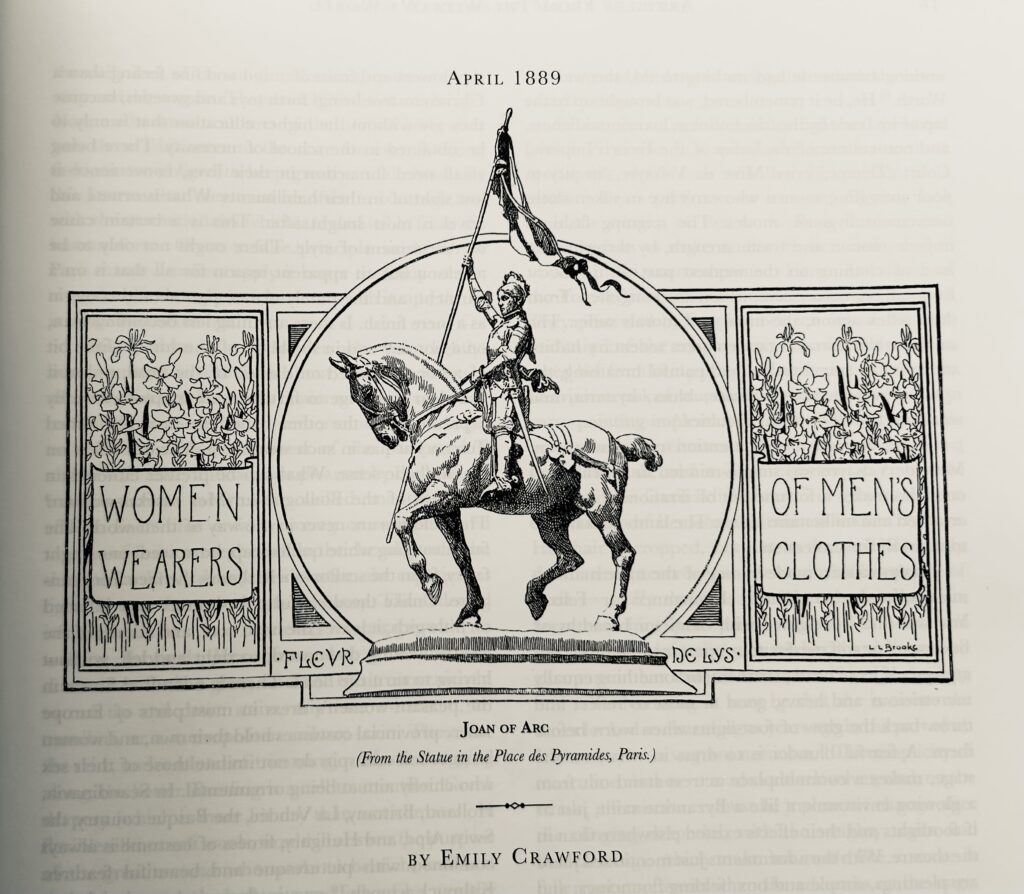

In ‘Women Wearers of Men’s Clothes’ (January 1889), prominent Irish-born journalist Emily Crawford presented readers with examples of women who had adopted masculine clothing and accomplished ‘heroic duties.’ In ‘Fans’ (January 1889), F. Mabel Robinson challenged the essentialism of Victorian orthodoxy in dress by pointing out that men once carried fans as an indicator of power. In ‘Gloves: Old and New’ (December 1888), dress historian S. William Beck, one of the few men who wrote regularly for The Woman’s World, wondered why men, once such decorative dressers, had become so ‘sober’. By mounting and facilitating challenges to gendered fashions, Wilde did much to advance the shared campaign of male aesthetes and New Woman activists to redefine rigid definitions of masculinity and femininity.

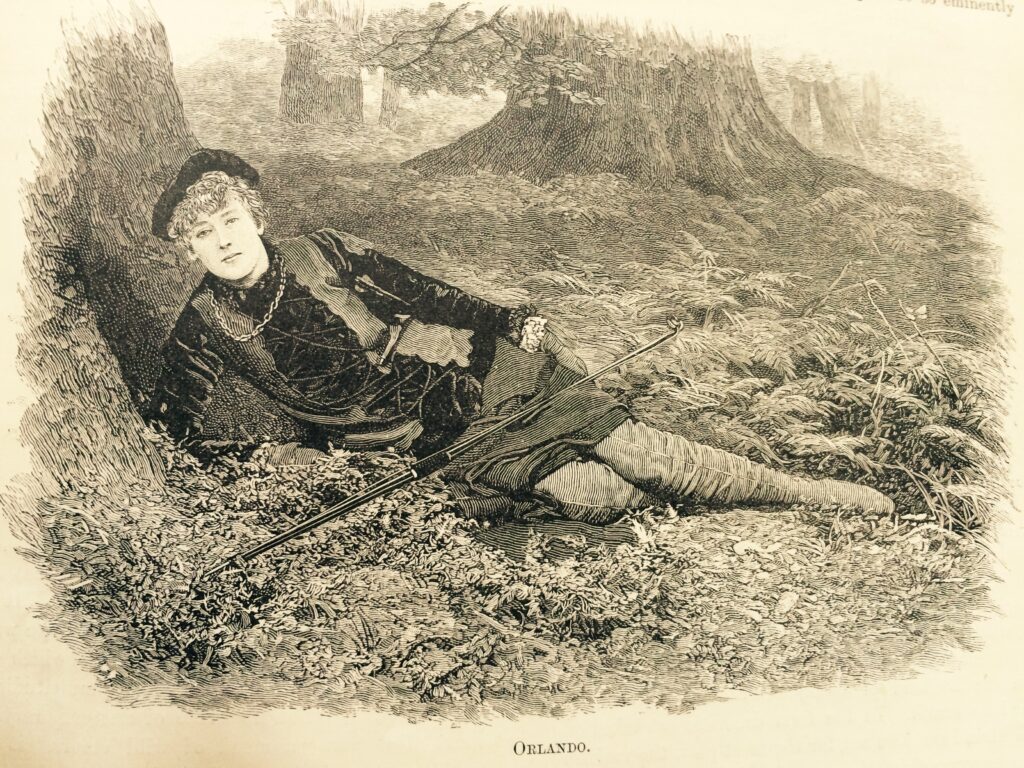

Imagery reinforced this message. Although Cassell dropped the ‘original coloured plates’ advertised so prominently when The Lady’s World was launched, illustrations remained a key feature of the new magazine. The first article Wilde published, ‘The Woodland Gods’ (November 1887), featured its author, Janey Sevilla Campbell, dressed as a young man to play Orlando in As You Like It, and embracing a woman while dressed as Perigot in Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess.

Wilde treated The Woman’s World as an extension of his own philosophy on art, aesthetics, and design. He involved himself intimately with the commissioning and selection of images and illustrations, working closely with Art Director Edwin Bale to ensure a new consistency across its pages. Stylistic forms recall a golden age of art and design. Decorated initial letters evoke medieval manuscripts and prefigure the style adopted by William Morris when he founded the Kelmscott Press in 1891. The artists who provided the beautiful images that accompanied many of the articles were almost exclusively men, one exception being artist Dorothy Tennant. Petra Clark has examined the way in which male artists negotiated aestheticism among themselves within the pages of The Woman’s World, and concludes that ‘Wilde’s aesthetic aims for the magazine in its entirety’, as ‘to elevate its content (and by extension, its readers) to a higher state of art and erudition’.[43] Under Wilde’s supervision, Clark continues, The Woman’s World encouraged ‘the assumed readership of educated middle- and upper-class women to actively work towards greater artistic sophistication.’[44]

The task of radically overhauling The Lady’s World, albeit self-imposed, was monumental. Before his first issue appeared, Wilde had complained that the ‘work of reconstruction was very difficult as The Lady’s World was a most vulgar trivial production, and the doctrine of heredity holds good in literature as in life.’[45] Much of his disenchantment was born of frustration rather than lack of commitment. In October 1887, he told Helena Swanwick that he was ‘not allowed as free a hand as I would like.’[46] As early as December 1887, he admitted that Cassell ‘was making strong protests against what they term the “too literary tendencies of the magazine”.’[47] The following month, he returned a submission to Oscar Browning, explaining that he was having ‘great difficulty about purely literary articles’.[48] In October 1888, the performance of The Woman’s World was reviewed by a senior editor at Cassell, likely Chief Editor John Williams, and several recommendations were made, including the reinstatement of Wilde’s lapsed editorial and the relocation of the fashion round-up to a more prominent position. Wilde was unhappy with many of the changes. In a letter expressing his hope that the board would authorise the purchase of a story by Frances Hodgson Burnett, he noted ‘under the new regime most of the articles will be written by regular contributors whose names are not of much value, though their work will be very good’. He was struggling with the practicalities of editing and complained that ‘without a staff of some kind a magazine with special illustrated articles cannot get on’.[49]

The challenges posed by the radical overhaul of an existing magazine in the face of fierce managerial opposition were exacerbated by Wilde’s increasing preoccupation with his own literary output. In ‘The Woman’s World: Oscar Wilde as Editor’, Anya Clayworth calculates that, while working for Cassell, ‘Wilde wrote seventy-two poems, reviews, essays, and stories for periodicals’.[50] These included ‘The Decay of Lying’, ‘Pen, Pencil and Poison’, ‘The Portrait of Mr W. H.’, ‘The Canterville Ghost’, ‘The Sphinx Without a Secret’, ‘Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime’, and The Happy Prince and Other Tales. He also kept up his reviewing for the Pall Mall Gazette and other periodicals. He attempted to divest himself of his monthly ‘Literary and Other Notes’, telling Reid: ‘There are many things in which women are interested about which a man cannot really write, and the commercial value of such notes should, I fancy, be considerable’.[51] He suggested Florence Fenwick Miller, who wrote ‘Ladies’ Notes’ for the Illustrated London News for thirty-three years. His request was refused and his editorial reinstated but demoted to the back of the magazine, although he was permitted to confine it to book reviews, many of them recycled. Such interference was wildly at odds with what he had described to Oscar Browning in the summer of 1887 as ‘a magazine that is to be under my management next October’.[52]

Fish, Wilde’s sub-editor, never doubted his loyalty to his ‘brilliant company of contributors which included the leaders of feminine thought and influence in every branch of work’.[53] He recalled how, when challenged by management, Wilde ‘would always express his entire sympathy with the views of the writers and reveal a liberality of thought with regard to the political aspirations of women that was undoubtedly sincere.[54] Fish’s description of a typical day towards the end of his boss’s tenure included the following: ‘He would sink with a sigh into his chair, carelessly glance at his letters, give a perfunctory look at proofs or make-up, ask “Is it necessary to settle anything to-day?” put on his hat, and, with a sad “Good-morning”, depart again’.[55] Merlin Holland, Wilde’s grandson, and Rupert Hart-Davis, when editing Complete Letters, date Wilde’s letter to ‘an income-tax inspector’ at the Inland Revenue, informing them ‘I am resigning my position here and will not be with Messrs Cassell after August’, to April 1889, two years after he had so enthusiastically accepted the role.[56]

The summer of 1889 was largely taken up with his own literary output. He travelled to Germany to discuss a possible staging of The Duchess of Padua (1883), his second play. Back in London, a meeting with J. M. Stoddart, editor of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, led to a commission for The Picture of Dorian Gray. In August 1889, he returned a story to Emma Mawer, accompanied by a letter, in Fish’s hand, informing her, ‘I am resigning the editorship of the Woman’s World after the October number’.[57] His departure was confirmed in a short announcement in The Literary World for September 1889: ‘Mr. Oscar Wilde retires from the editorship of the Woman’s World with this month’s issue’ [October 1889].[58] Assuming Wilde’s departure signalled the end of The Woman’s World, London newspaper the Star declared triumphantly:

So, the Woman’s World is dead, and Oscar Wilde’s occupation as its editor has gone. The dead magazine and the flourishing Queen and Lady’s Pictorial hold a strong lesson to those who believe that women can in everything be the equal of men. The Woman’s World was started with the idea that there were enough women of culture to support a really high-class women’s magazine. In a superior artistic form the Woman’s World also catered for the fashionables. By good articles and better illustrations it was thought to found a literary feature which would quickly be appreciated by women who could not find sufficient soul-satisfying reading in the twaddly pages of the ordinary women’s paper. The experiment has been a decided failure. It went too high.[59]

Cassell announced plans to reconfigure The Woman’s World, taking it closer to its rivals with the promise of ‘a series of interviews with prominent Englishwomen at home; practical papers on employments for women; women in other lands, their social position, occupations, &c.; the economy of dress (including practical information for amateur dressmaking); papers on domestic decoration, artistic recreations for women, &c’.[60] This revised magazine was generally welcomed. The London Daily Chronicle declared: ‘An attempt to render the Woman’s World somewhat more homely and practical is likely to be regarded as an improvement.’[61] However, a renewed focus on fashion prompted The Women’s Penny Paper (1888-1893), the most vigorous feminist paper of its time, to scold: ‘To dress is surely not considered the first or the only duty of women, even by their greatest enemies.’[62] Interesting insights are provided in the correspondence of Charlotte Stopes, a contributor to The Women’s Penny Paper and member of the Rational Dress Society, who had, largely unsuccessfully, submitted several articles to Wilde directly and through Constance Wilde, a fellow member of the Rational Dress Society. Stopes appears to have complained about a deterioration in the magazine in the wake of Wilde’s departure. A fascinating reply, dated 15 January 1890, and signed ‘the editor’, includes the following:

I take note of what you say about the magazine, and hope that as time goes on you will find it holds the balance pretty evenly between the higher and the lower. What we want to do is justify its title, which is neither the ‘Intellectual Woman’s World’ or the ‘Frivolous Woman’s World’ but the ‘Woman’s World’. If we do that I am sure you will be the last to blame us.[63]

Her article on Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was rejected on the grounds that it was ‘too profound for the class of readers we are now aiming at’.[64] Wilde was not immediately replaced as editor, fuelling speculation as to who was compiling the magazine during the twelve months it continued to appear. On 2 April 1890, regional newspaper the Pateley Bridge & Nidderdale Herald reported that the new editor was ‘Miss Billington, an Echo lady journalist’.[65] This was journalist Mary Frances Billington, in her late twenties by then, who did write a series of articles for The Woman’s World, beginning with ‘Journalism as a Profession for Women’ (November 1889). There is little to link her to this role, although she was a likely candidate. That same year, she was appointed first woman special correspondent on women’s interests at the newly launched Daily Graphic, she presided over the women’s department of the Daily Telegraph from 1897 for many years, and she was President of the Society of Women Journalists for a time. It is possible that she was responsible for the new ‘Notes and Comments’ that appeared from November 1889 onwards, four pages of short notes in the format Wilde had suggested to Reid in October 1888.

Rather than slump into a terminal decline, The Woman’s World came out to general acclaim until October 1890, facilitating a third bound volume. On 17 November 1890, the Literary World reported that ‘the support accorded to The Woman’s World has proved insufficient to justify its continuance, and the volume just completed brings its publication to a close’.[66] Reporting that it had ‘died a natural death with the October number’, the ‘London correspondent’ for the Northern Echo declared, with misplaced optimism: ‘The fact is that the idea of the magazine was an anachronism. Except so far as fashion-plates are concerned, the woman’s world nowadays is the same as the men’s.’[67]

Wilde was not, perhaps, a natural editor, and his true talents and interests lay elsewhere but his time with Cassell, far from being wasted, honed his ability to give the public what they wanted. As Clayworth puts it: ‘Wilde’s editorship is not, therefore, merely the stuff of biographical anecdote but a significant indicator of a change in his writing tactics.’[68] Many of the ideas he engaged with in his editorials and in articles he commissioned resurfaced in his essays, stories, and plays. A re-examination of The Woman’s World is a worthwhile exercise since a key legacy of Wilde’s editorship lies in the progressive, erudite articles he published across the twenty-four issues that were under his control. At a time when outspoken women were often denied an outlet to express their frustrations, he gave them a platform for their activism and supported them in his editorials. He also inspired at least one woman editor who followed him. In ‘A Female Aesthete at the Helm: “Sylvia’s Journal” and “Graham R. Tomson”, 1893-1894’, Linda K. Hughes describes how Sylvia’s Journal, the aesthetic magazine Tomson (who became Rosamund Marriott Watson in 1894) edited from January 1893 until April 1894, ‘seemed deliberately designed by format and content to echo and rival what Oscar Wilde had earlier achieved in Woman’s World’.[1] Tomson even published the remainder of a series on poets and their treatment of woman that Wilde had commissioned from Irish writer and family friend Katharine Tynan. Perhaps the last word is best left to the London Times, who greeted the appearance of this ground-breaking magazine by declaring ‘The Woman’s World, edited by Mr. Oscar Wilde, gracefully got up as it is in every respect, has taken a high place among the illustrated magazines. Written by women, for woman and about women, striking out an original line, it merited the success it has obtained.[69]

Eleanor Fitzsimons is an Irish researcher and biographer who specialises in recovering women’s lives. She has an MA in Women, Gender and Society from University College Dublin (also B. Comm. and M.B.S.). She is the author of Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde Was Shaped by The Women He Knew (Duckworth, 2015), The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit (Duckworth, 2019, winner of the Rubery Prize for non-fiction, a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2019, and included in the Washington Post Top 50 Non-Fiction Books of 2019 and the Dallas Morning News Top 100 Books of 2019), and the compiler and editor of Selected Articles from The Woman’s World, Edited by Oscar Wilde (Oscar Wilde Society, 2024). She is co-editor, with the late Eibhear Walshe, of Speranza: Poems by Jane Wilde: Selected and Introduced by Eibhear Walshe and Eleanor Fitzsimons (Liverpool University Press, 2025). Her work has been published in several journals and academic books, among them Fashion and Material Culture in Victorian Fiction and Periodicals (eds. Janine Hatter and Nickianne Moody, Edward Everett Root, 2019) and George Egerton Terra Incognitas (eds. Isobel Sigley, Whitney Standlee, Routledge, 2024). She is an honorary patron of the Oscar Wilde Society and is on the editorial board of society journal The Wildean.

[1] Anna de Brémont (1911) Oscar Wilde and His Mother, London: Everett & Co., Ltd., 73

[2] Rob Marland and Wolfgang Maier-Sigrist (2023) ‘Four unpublished Oscar Wilde letters drafted by assistants at The Woman’s World’, The Wildean 62, 19-44

[3] Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis (editors). The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (CL) Fourth Estate, 2000, 297

[4] CL, 297

[5] Cynthia Lesley White (1970). Women’s Magazines, 1693 – 1968.London: Michael Joseph, 58

[6] The prospectus is reproduced in Michael Seeney (2023) Oscar Wilde as Editor; An Index to Woman’s World, High Wycombe: The Rivendale Press, 132-3

[7] Sos Eltis (1996) Revising Wilde: Society and Subversion in the Plays of Oscar Wilde, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 8

[8] CL, 297

[9] CL, 299

[10] CL, 318

[11] CL, 317

[12] Stella Newton (1974) Health, Art and Reason: Dress Reformers of the 19th Century, London: J. Murray, 119

[13] Laurel Brake (1994) ‘Oscar Wilde and The Woman’s World’, Subjugated Knowledges, Journalism, Gender, and Literature, in the Nineteenth Century, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 127-147, 142

[14] Margaret Beetham and Kay Boardman (eds) (2001) Victorian Women’s Magazines: An Anthology, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 90

[15] Arthur Fish (1913) ‘Oscar Wilde as Editor’, Harper’s Weekly, 4 October 1913, 58, 18-20, 18

[16] de Brémont, 73

[17] Derby Mercury, 2 January 1889, 6

[18] Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser, 5 May 1880

[19] CL, 314

[20] Ian Small (1993) ‘Oscar Wilde as a Professional Writer: Evidence from the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center’, Library Chronicle of the University of Texas at Austin, 53, 37

[21] CL, 324

[22] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, November 1887, 39

[23] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, January 1888, 135-6

[24] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, March 1888, 231

[25] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, January 1888, 136

[26] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, December 1887, 85

[27] CL, 301

[28] Isobel Hurst (2009) ‘Ancient and Modern Women in the Woman’s World’ in Victorian Studies 52, no. 1, Autumn 2009, 42-51, 42

[29] CL, 311

[30] CL, 327

[31] CL, 325

[32] Ella Hepworth Dixon (1930) As I Knew Them; Sketches of People I Have Met on the Way, London: Hutchinson, 34

[33] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, December 1887, 81

[34] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, January 1888, 133

[35] Nicholas Frankel (2010) ‘Vernon Lee and A. Mary F. Robinson: Two New Sources for Oscar Wilde’s “Dorian Gray”’, The Wildean 36, January 2010, 69-76

[36] Marion Thain (2011) ‘Birmingham’s Women Poets: Aestheticism and the Daughters of Industry’ in Female Aestheticism, edited by Catherine Delyfer, Cahiers Victoriens et Édouardiens, Autumn 2011, 37-57. https://journals.openedition.org/cve/1044 This is refuted by Josephine M. Guy in ‘An Allusion in Oscar Wilde’s “The Canterville Ghost’”, Notes and Queries, 243.

[37] James Diedrick (2018) “Mathilde Blind (1841-1896),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, https://1890s.ca/blind_bio/

[38] Complete Letters, page 297

[39] The Editor (Oscar Wilde). ‘Literary and Other Notes’, December 1887. The Woman’s World Volume I, Cassell & Company, page 84.

[40] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, November 1887, 40

[41] Loretta Clayton (2013) ‘Oscar Wilde, Aesthetic Dress, and the Modern Woman’ in Joseph Bristow (ed) Wilde Discoveries, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 143.

[42] ‘The Editor’ (Oscar Wilde) ‘Literary and Other Notes’, The Woman’s World, December 1887, 84-5

[43] Clark, 377

[44] Clark, 398

[45] CL, 332

[46] CL, 325

[47] CL, 337

[48] CL, 339

[49] CL, 362

[50] Anya Clayworth (1997) ‘The Woman’s World: Oscar Wilde as Editor: 1996 VanArsdel Prize’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 30.2, 84–101, 97

[51] CL, 363

[52] CL, 313

[53] Fish (1913), 18

[54] Fish (1913) 18

[55] Anon (1922) Story of the House of Cassell, London: Cassell & Co, 134

[56] CL, 395

[57] CL, 411

[58] ‘Periodicals’, The Literary World, 14 September 1889, Volume 20, 308

[59] ‘Notes and News’, The Cornish Telegraph, 26 September 1889, 3

[60] Published in Morning Post, 30 September 1889, 2

[61] London Daily Chronicle, 5 November 1889, 6

[62] ‘Reviews: Magazines of the Month’, Women’s Penny Paper, 13 September 1890, 557

[63] Rob Marland, ‘Oscar Wilde’s Assistants at The Woman’s World, June 13, 2023, available at Marland http://marlandonwilde.blogspot.com/2023/06/oscar-wildes-assistants-at-womans-world.html

[64] Marland, http://marlandonwilde.blogspot.com/2023/06/oscar-wildes-assistants-at-womans-world.html

[65] ‘Spring’s Return’, Pateley Bridge & Nidderdale Herald, 5 April 1890, 4

[66] Reported in ‘Gossip of the Day’, Shields Daily Gazette, 17 November 1890, 4

[67] ‘London Notes’, Northern Echo, 8 November 1890, 3

[68] Clayworth, 85

[69] The Times, 7 December 1888, 5