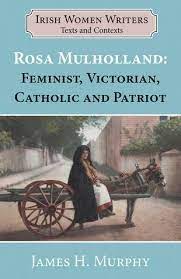

Rosa Mulholland republished on the centenary of her death

James H. Murphy

Rosa Mulholland, Lady Gilbert (1841-1921), died in the spring of 1921. Spring 2021, the centenary of her death, marks the publication of Rosa Mulholland: Feminist, Victorian, Catholic and Patriot, published by Edward Everett Root and edited by James H. Murphy. This reader of Mulholland’s work is part of the Irish Women Writers: Texts and Contexts series, whose editors are Kathryn Laing and Sinead Mooney, co-founders of the Irish Women’s Writing Network 1880-1920. The book consists of an introduction and bibliography of Mulholland’s work, and seven selections from her work. These have been chosen on the basis of their status as significant interventions into various issues of importance and also for being illustrative of the variety of topics she addressed at different points in her career.

Mulholland wrote over thirty novels for adults and young readers and four works specifically for children in the years between the publication of her first novel in 1864 and her death in 1921. There are extracts in the reader from four of these novels: Dunmara (1864), which concerns professional aspiration among young women in mid-Victorian London; Marcella Grace (1886), which deals with a young woman thrust into the role of landlord during the Irish land war; Nanno, A Daughter of the State (1899) about the moral dilemmas facing a single mother; and The Return of Mary O’Morrough (1908), which is concerned with the pressures on an older woman both to be economically generative and to maintain a level of youthful beauty in order to be marriageable. Also included are ‘The Hungry Death’ (1880), a story about famine which is representative of Mulholland’s extensive output in short fiction, and ‘Wanted an Irish Novelist’ (1891), which affords readers a view of an intervention by Mulholland in the debate about Irish literature that was topical in the 1890s. Finally, it is important also to note that Mulholland was an impressive poet who collected her verse in three volumes over a seventeen-year period towards the end of her career. Selections from these works are also reproduced in the volume.

Mulholland had the oddest of nineteenth-century Irish backgrounds. She was a well-off Catholic from Ulster, a province with few centres of middle-class Catholic life. The 1860s proved to be a remarkable decade for her as a young writer. In London she was befriended by perhaps the leading Victorian painter of the time, Sir John Everett Millais (1829-96) , who illustrated some of her published work. At the time that Mulholland was writing, fiction was often serialised in magazines and throughout her career many of Mulholland’s novels were issued in periodicals before they became books. Mulholland enjoyed a good deal of success in the London of the early 1860s through being published in prestigious literary magazines. For example, the Cornhill Magazine published her poem, ‘Irené’, in 1862 and in the same year London Society published a short story based on her experiences at art school.

Artist: John Everett Millais Engraver: Dalziels 1862 Wood engraving 3 3/4 x 2 3/4 inches Illustration for Rosa Mulholland’s ‘Irene’, facing p. 547 Scanned image and text by Simon Cooke

Mulholland’s greatest success in the 1860s, however, came through her association with Charles Dickens (1812-70). He published short stories and poems by her and serialized her second and third novels, Hester’s History and the Wicked Woods of Tobereevil, in his own magazine, All the Year Round. When Tauchnitz, the German publisher of British writing, published No Thoroughfare by Dickens and Wilkie Collins in 1868 they included Mulholland’s The Late Miss Hollingford with the volume.

With Dickens’s death in 1870 Mulholland began to shift away from London and moved towards Dublin, where she eventually came to live. Despite the fact that she continued to issue her books with London publishers and also to contribute shorter pieces to London magazines, it was in Dublin that Mulholland found a journal and an editor with whom she was to be associated for the rest of her career: the Irish Monthly and Matt Russell (Father Matthew Russell, S. J.). In looking back on the first twenty-five years of the magazine in 1897 Russell singled out Mulholland as a key figure without whom the magazine would not have thrived or perhaps even survived. She published many short stories in the magazine and two of her most significant novels were serialized in the Irish Monthly before they were published in book form: a romance, The Wild Birds of Killeevy, in the late 1870s, and Marcella Grace in 1885.

In 1891, aged fifty, Rosa Mulholland married the Dublin historian John T. Gilbert (1829-98). They lived at Villa Nova in Blackrock, Co. Dublin, and she became Lady Gilbert when he was knighted in 1897. She subsequently wrote a biography of him, as well as editing some of his unfinished work, after he died unexpectedly just seven years after their marriage.

With an established presence in the British publishing market, a home base in Dublin and an outlet in the Irish Monthly, Mulholland was able to create a balance that suited her as a writer, particularly of fiction. On the one hand, her work was acceptably Victorian and yet on occasion it promoted advanced views on the plight and role of women. On the other hand, it also presented a positive view of Catholics and occasionally a critique of Ireland’s position in the British dispensation. Her readership was a general Victorian middle-class audience, though with a particular focus on Irish middle- and upper-middle-class Catholics such as herself. Her objectives when it came to both groups were largely similar. Upper-middle-class Irish Catholics wanted to be accepted as respectable Victorians. This involved modifying the British view of Ireland as lawless and its peasantry as violent.

Among those who wrote about Mulholland after her death was her friend and fellow writer Katharine Tynan (1859-1931). Their relationship was an odd mixture of affection and wariness: Tynan said that she never revealed her full self to Mulholland, but that when Mulholland was angry with her it was anger with someone she loved. As Mulholland wrote no memoir of her own, we are left to sift the truth from Tynan’s bruised reminiscences. Tynan presents a rather timid and withdrawn version of Mulholland. Certainly, Mulholland’s early promise in London gave way to a more conventional later life in Dublin. But, Mulholland’s writing at times evidences a far from timid and repressed approach. The women who populate her novels are not at all compliant. They are often clear sighted and determined in the face of considerable difficulties and obstacles. Perhaps the inner Mulholland was not entirely the person whom Tynan observed. Perhaps, too, Mulholland had not entirely revealed herself to Tynan.

Rosa Mullholland’s Grave, Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin

JAMES H. MURPHY has been Professor of English at DePaul University, Chicago, and at Boston College. He is a scholar of nineteenth-century Ireland. He is the author of six monographs and editor or co-editor of ten works including The Oxford History of the Irish Book, iv, 1800–1891 (2011). His principal areas of research are the political history and the history of fiction of the century. He has published three monographs over the past decade, Irish Novelists and the Victorian Age (Oxford, 2011), Ireland’s Czar: Gladstonian Government and the Lord Lieutenancies of the Red Earl Spencer, 1868–1886 (2014)and The Politics of Dublin Corporation, 1840–1900: From Reform to Expansion (2020). His work has been seminal in the recovery and recuperation of Irish women’s writing 1880-1920, and he was the subject of an Irish Women’s Writing Network ‘Research Pioneers’ interview in December of 2019, available here: https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/research-pioneers-3-james-h-murphy/

Would you like to submit a blogpost? Check out our guidelines here or email Dr Deirdre Flynn.