Writing the Aran Islands: The Curious Case of Nurse B. N. Hedderman

Theo Joy Campbell

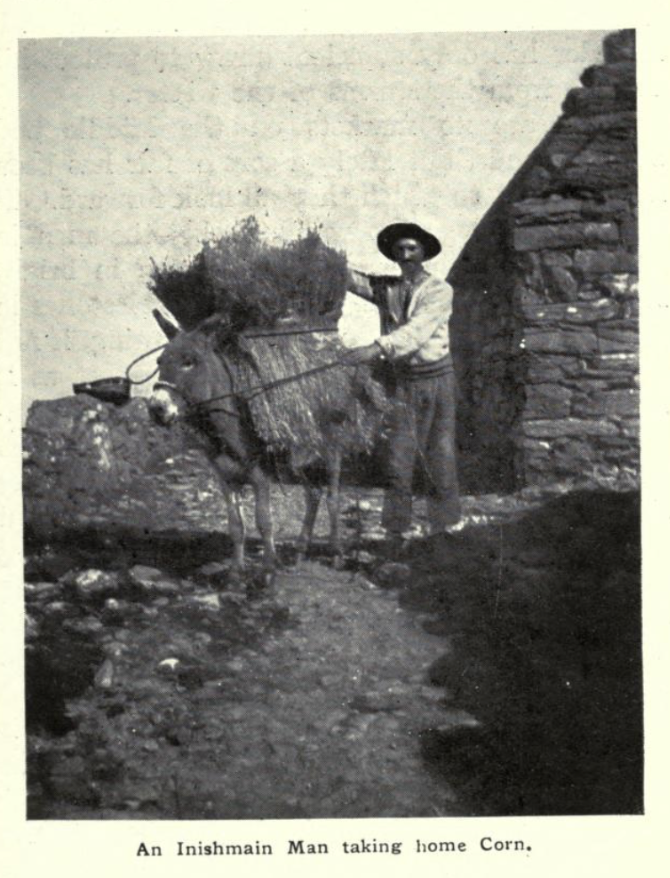

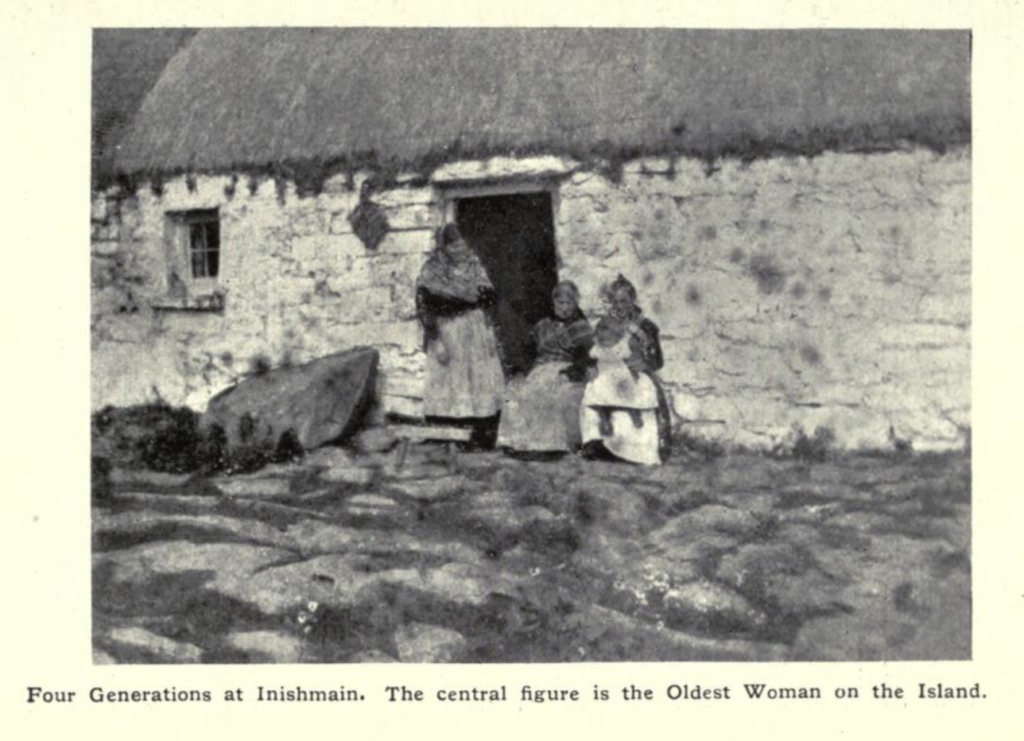

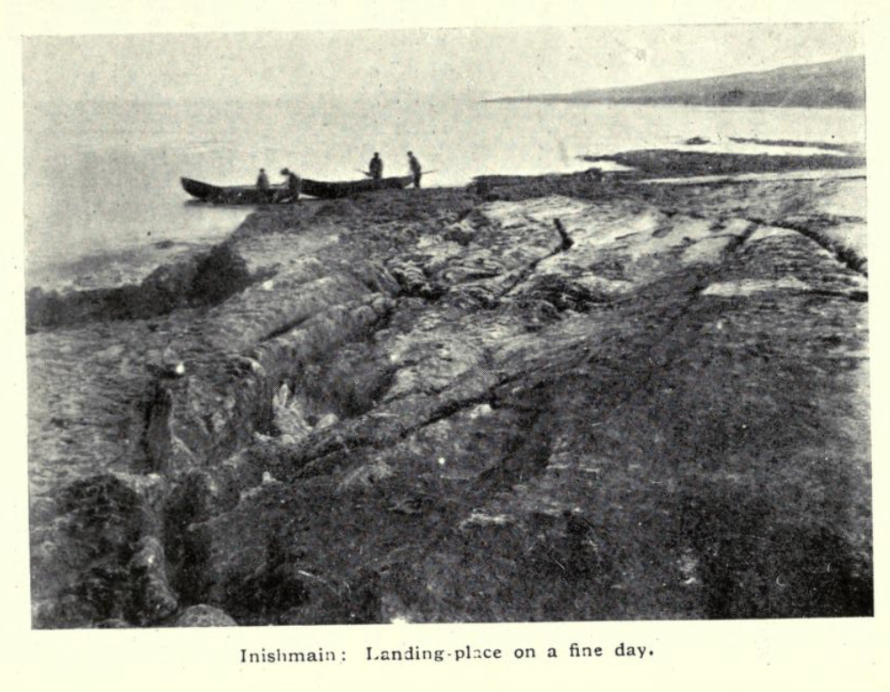

District Nurse B. N. Hedderman’s 1917 memoir, Glimpses of my Life in Aran, was a puzzle I needed to solve.[i] I first stumbled upon it while researching J. M. Synge and his famous 1903 travelogue The Aran Islands. After reading Glimpses, I was surprised to learn that Hedderman almost never appears in contemporary scholarship about Synge’s book. Scholars often read The Aran Islands in conversation with contemporaneous Aran nonfiction, like Úna Ní Fhaircheallaigh’s Smaointe ar Árainn (Thoughts on Aran) and C. R. Brown and Alfred Haddon’s “The Ethnography of the Aran Islands,” particularly when they are considering Synge in the context of colonialism. Hedderman’s memoir seemed like an illuminating addition to this conversation—she had spent far more time on the islands than Synge or Ní Fhaircheallaigh but her often condescending tone landed closer to that of Haddon and Brown. Hedderman grippingly details the harsh realities of rural poverty, but her claim that the islanders were full of “black ignorance” and her choice to call their customs “barbaric” seem to reproduce Anti-Irish propaganda. Her tone cuts against everything the Irish revival was trying to accomplish. Why would a woman who lived nearly two decades among the islanders, who regularly risked her life to save theirs, replicate the rhetoric of their oppressors? And why was no one talking about her, at least in literary scholarship? Further fuelling my curiosity was the lack of personal details in the book, despite its claim to be a memoir: I did not know whether Hedderman was Catholic or Protestant, whether she knew any Irish at all before arriving on Aran, or even what her first name was, much less how she may have felt about Irish nationalism or the cultural revival movements.

Hedderman’s absence from most scholarly literature is likely due to her obscurity. Synge, Ní Fhaircheallaigh, Haddon, and Brown all earned fame for literary and/or scholarly output that went far beyond their writings on Aran while Glimpses is Hedderman’s only published work. But there is one scholarly corner that picks up on the significance of Glimpses. According to historian Ciara Breathnach, Glimpses is the only known longform account of what life was like for nurses bringing modern medical innovations to the remotest corners of Ireland in the early twentieth century.[ii] The book has thus received attention in Irish medical histories. These citations tend to take the memoir as a factual record, never considering how it is written, and they generally don’t include further details about Hedderman beyond what she presents in Glimpses. To answer the questions I was interested in—to understand why Hedderman wrote the way she did and how Glimpses might or might not fit into the body of revivalist literature about the Aran islands—I needed to know more about the elusive Nurse Hedderman.

So I set out to see what I could learn. I found traces of her in the minute books of several Boards of Guardians she worked for. And I found her again in the meeting notes of the Congested Districts Board, which she wrote to repeatedly with her advice for more effectively helping the Aran islanders. Even better, I found several letters to the editor she had written, published both in nationalist newspapers like An Claidiheamh Solius and the Connaught Tribune and in British nursing magazines like the Nursing Times and the British Nursing Journal. With these sources, I’ve been able to piece together a more complete picture of Hedderman both as a nurse and as a writer and to begin to understand the choices she made while writing Glimpses of my Life in Aran. But most importantly: I found out who Hedderman was.

Hedderman’s first name was Bridget. She was Catholic. She grew up working class in the Gaeltacht in Clare. She lost her father to drowning when she was seven years old. These facts were surprising, given the memoir’s unsympathetic tone towards traditional cultural beliefs—Hedderman had far more in common with the Aran islanders than she did with Synge or Ní Fhaircheallaigh. I was left to wonder: why doesn’t she show more understanding for impoverished mothers clinging to the same comforting beliefs she was likely raised with?

In her letters to Irish newspapers, Hedderman aligns herself with her patients and displays the empathy that sometimes seems absent in the memoir. In a 1913 letter to the editor of the Irish Independent, she defends the islanders against claims that their superstitions caused a recent epidemic on Inis Oírr. She admonishes government officials for policies that trap the islanders in poverty, making effective sanitation impossible. Hedderman writes: “The fear of contracting the infective material is alive in the islands, as they have been taught to recognize the danger of mingling indiscriminately, but they have no means yet able to combat the invisible microbe lurking in their damp, insanitary walls and earth-cold floors. And is not this preventative in the hands of those who govern them?”[iii] In the memoir, Hedderman often implies that the islanders cause their own suffering by clinging to outdated cultural beliefs, but in this letter, she blames their suffering on poverty exacerbated by unjust governance.

The seeming inconsistency in Hedderman’s opinions evidences her ability to adapt her writing for different reading audiences and to different ends. Her letter to the Irish Independent, for instance, was a direct form of political advocacy, urging Irish people to support policies that would best aid the Aran Islanders. The memoir, however, was not intended to be a direct form of activism in the same way, and it was not written for an Irish audience. Hedderman published Glimpses with the British medical press John Wright and Sons, and her audience was, as such, a highly educated British one, unlikely to appreciate a nuanced take on the idea that fairies could take children away or that the evil eye could cause infections. It did, however, enjoy her ethnographic tone and her toeing of the line on the benefits of bringing modernity to remote places: the British Journal of Medicine, for example, praised Glimpses by stating that “The charm of the style and the interest of the matter are so irresistible that it is to be hoped further instalments will soon appear.”[iv] Hedderman successfully wrote a book about the Aran Islands that doctors wanted to buy.

This framing of her mission makes it seems self-centered, but in fact her economic aims were meant to serve her patients just as much as her nursing practice was. Hedderman told the British Journal of Nursing that she was selling the book “to raise the sum of £200 to build a little cottage, for the strain of having to pay rent out of a salary of less than £1 a week is almost unendurable. Both the Congested Districts Board and the Galway Guardians have refused for financial reasons to build the cottage.”[v] This revelation raises a striking possibility: in writing her book, Hedderman crafted a narrative about Aran that would be marketable to those with the disposable income to buy it, rather than a narrative that would present the islanders to the world as ideal representatives of Irish culture, as Synge and Ní Fhaircheallaigh did.

Thus, despite its colonialist tone, Glimpses may be at least as anticolonial as Thoughts on Aran or The Aran Islands. The difference comes from Hedderman’s method, a method quite suited to the practicality of her position. Synge and Ní Fhaircheallaigh wrote to change the rhetoric surrounding rural Ireland, but Hedderman wrote to provide material support to its residents. Both tactics serve the mission of Irish cultural revival even if Hedderman’s book, without context, seems to do to the opposite. I think Hedderman felt comfortable writing in a way that could potentially be misconstrued because of her physical and cultural proximity to the poor, rural Irish culture that middle- and upper-class Revivalists rhetorically invoked. Hedderman expressed her belief in the resilience of that culture in a 1907 letter to An Claidiheamh Solius: “Inishmaan will remain a Gaelic stronghold…Fruitless, indeed, would be any attempt to Englishise it.”[vi]

Theo Joy Campbell is a PhD student in literary studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. They previously completed an MA at Villanova University, where they wrote a thesis focusing on the memoir of Bridget Hedderman, a nurse working in the Aran Islands from 1903-1922. Theo’s research sits at the intersection of folklore and medical humanities; they are particularly interested in how gendered assumptions impact depictions of supposed tensions between folk medicine and “scientific” medicine in nineteenth and early twentieth century writing.

ajcampbell25 [@] wisc.edu

[i] Bridget Hedderman, Glimpses of my Life in Aran: Some Experiences of a District Nurse in these Remote Islands Off the West Coast of Ireland, (Bristol: John Wright and Sons Ltd, 1917).

[ii] Ciara Breathnach, “Lady Dudley’s District Nursing Scheme and the Congested Districts Board, 1903-1923,” in Gender and Medicine in Ireland 1700-1950, ed. Margaret H. Preston and Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2012), 271.

[iii] “The Aran Islands Fever,” Irish Independent, Dec. 20, 1913.

[iv] “Notes on Books,” British Medical Journal, Oct. 6, 1917.

[v] “Glimpses of my Life in Aran,” British Journal of Nursing, Aug. 25, 1917.

[vi] “English in Aran,” An Claidheamh Solius, Nov. 9, 1907.