Teaching Charlotte Riddell’s Irish Gothic Fiction

Dr Dara Downey

About a year ago, I found myself (in a situation that will be familiar to many scholars) teaching far outside my comfort zone. I am first and foremost an Americanist, and, rightly or wrongly, have spent much of my career carefully avoiding what often seems to me to be the ideologically and emotionally fraught terrain of Irish literature in general, and of the Anglo-Irish Revival in particular. This time around, however, it was unavoidable, though thankfully, the system then in place where I was working meant that the second-year seminars I was teaching needed only a very broad association with the accompanying lectures. Read More

About a year ago, I found myself (in a situation that will be familiar to many scholars) teaching far outside my comfort zone. I am first and foremost an Americanist, and, rightly or wrongly, have spent much of my career carefully avoiding what often seems to me to be the ideologically and emotionally fraught terrain of Irish literature in general, and of the Anglo-Irish Revival in particular. This time around, however, it was unavoidable, though thankfully, the system then in place where I was working meant that the second-year seminars I was teaching needed only a very broad association with the accompanying lectures. Read More

IASIL 2017: New Horizons for Irish Literary Studies

by Rebecca Graham, University College Cork

If, during the last week of July, you were searching for members of the International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures (IASIL), your quest would have taken you all the way to Singapore. This city-state in South East Asia may not be the first place you think of when considering a major conference of Irish writing, but this is where IASIL’s annual conference was held this year and it turned out to be the perfect setting. Read More

If, during the last week of July, you were searching for members of the International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures (IASIL), your quest would have taken you all the way to Singapore. This city-state in South East Asia may not be the first place you think of when considering a major conference of Irish writing, but this is where IASIL’s annual conference was held this year and it turned out to be the perfect setting. Read More

Expanding Connections: Bodies in Transit 2

by Dr Maureen O’Connor, UCC

In 2015, the Spanish government funded an international research project, “Bodies in Transit/ Cuerpos en Tránsito”, involving a number of scholars interested in representations of gender and difference in the present moment, using theories of posthumanism (especially those of Rosa Braidotti and Donna Haraway) and globalisation and the transnational, with special emphasis on the implications of neoliberalism for conceptualising subjectivity. The success of this important project has inspired the directors to propose a “Bodies in Transit 2: Genders, Mobilities, and Interdependencies. Read More

In 2015, the Spanish government funded an international research project, “Bodies in Transit/ Cuerpos en Tránsito”, involving a number of scholars interested in representations of gender and difference in the present moment, using theories of posthumanism (especially those of Rosa Braidotti and Donna Haraway) and globalisation and the transnational, with special emphasis on the implications of neoliberalism for conceptualising subjectivity. The success of this important project has inspired the directors to propose a “Bodies in Transit 2: Genders, Mobilities, and Interdependencies. Read More

Impressions of RSVP’s (Research Society for Victorian Periodicals) 2017 Conference in Freiburg, Germany

Nora Moroney, Trinity College Dublin

Germany’s Black Forest, surrounding the city of Freiburg, does not conjure up immediate associations with Victorian periodicals, familiar as it is to most of us for picturesque scenery and delicious confectionary. But last month its historic university played host to RSVP’s annual conference on the theme of ‘Borders and Border Crossings’. Over seventy scholars from Europe, the UK, Ireland and the US spent three days discussing the varieties of periodical culture in the nineteenth century. There was a pleasing congruency to the theme and location too – situated close to the borders of Germany, Switzerland and France, Freiburg provided the perfect setting for such an international cohort. Read More

The Irish Identity Of George Egerton

By Eleanor Fitzsimons

On 19 July 2017, Dr Whitney Standlee of the University of Worcester wrote a wonderful blog post for the Irish Women’s Writing Network describing her experiences at George Egerton and the fin de siècle, an inaugural two-day conference held at Loughborough University in April 2017. On day two, Dr. Standlee delivered a fascinating paper on Egerton’s ‘Portrayal of Mindscape and Landscape in the Norwegian Context’. In her blog post, she mentioned my paper on the Irish context of Egerton’s writing. Since this seems like a perfect topic for the Irish Women’s Writing Network, I have summarised my key points here. Read More

On 19 July 2017, Dr Whitney Standlee of the University of Worcester wrote a wonderful blog post for the Irish Women’s Writing Network describing her experiences at George Egerton and the fin de siècle, an inaugural two-day conference held at Loughborough University in April 2017. On day two, Dr. Standlee delivered a fascinating paper on Egerton’s ‘Portrayal of Mindscape and Landscape in the Norwegian Context’. In her blog post, she mentioned my paper on the Irish context of Egerton’s writing. Since this seems like a perfect topic for the Irish Women’s Writing Network, I have summarised my key points here. Read More

George Egerton and the Fin de Siècle

Dr Whitney Standlee, University of Worcester

I remember precisely the moment I first discovered her. It was twelve years ago, I was sitting on a chair in a foyer waiting to meet with my prospective MA supervisor, and I was reading a story I had started the night before: a story I found promising in its opening pages and which grew ever more exciting as I read it. It was an 1890s work of short fiction, written by a woman who used a male pseudonym, and it concerned the experiences of a female narrator, a working woman, as she made her way from Norway to England by ship. Comprised primarily of a tale within a tale told to the narrator by a fellow traveller – a female academic (of all things!) – about the adopted daughter she has nicknamed ‘The White Elf’, the story was most intriguing to me because it included not only a challenging of gender roles but also an experimentation with literary form that made it seem well ahead of its time. I finished the story as I waited, and when called into the office, immediately announced that I would be doing my MA on the author of that short story, George Egerton. That was the first time I was faced with the question ‘who is George Egerton?’, but it was destined to be a query I would become intimately familiar with in the ensuing years.

I soon learned, however, that other, far more eminent commentators were not as impressed with Egerton’s work as I was. Although Holbrook Jackson, in his 1913 study The 1890s, had drawn attention to her literary innovations, he treated her primarily as a footnote to the era rather than a primary player in it. Terence de Vere White was far more critical of both her and her work in his A Leaf from the Yellow Book (1958) – for many their first introduction to Egerton’s life and letters, and not an encouraging one. Elaine Showalter, too, dismissed her as a ‘wasted talent’ even as she held Egerton up as an exemplar of early ‘feminist’ writers in A Literature of Their Own (1978).

Such prominent (de)valuations consistently caused me to question the validity of my own judgment and the legitimacy of the study I was undertaking. Yet I could not help but notice that there were growing numbers of academic researchers, the majority of them female, who were beginning to reassess Egerton’s legacy. These included Nicole Fluhr, Shanta Dutta, Iveta Jusová, Sally Ledger, Scott McCracken, Ann Heilmann and a notable Irish contingent that counted Gerardine Meaney, Heather Ingman and Tina O’Toole among its number. Especially important was the pioneering work on Egerton done by a woman named Margaret Stetz, whose PhD thesis, completed in 1982 at Harvard, was then and remains the seminal study of Egerton’s life.

Fast forward twelve years to 8 April 2017 at Loughborough University, where the second day of a two-day conference on ‘George Egerton and the Fin de Siècle’ is underway. It opens with a keynote address by Margaret Stetz, now Mae & Robert Carter Professor of Women’s Studies at the University of Delaware. Regrettably, I am only able to attend the conference’s second day, but by the time I arrive the atmosphere is electric. Dozens of presenters and delegates are in the audience, and Stetz’s tales of coming to Egerton, and fighting against the damaging legacy of A Leaf from the Yellow Book, cement her status as a pathmaker in what is now known as ‘Egerton studies’. Throughout the two days of the conference, paper after paper focuses on the ways in which Egerton’s work thwarts both gendered and literary conventions and challenges established boundaries. Those boundaries include both gendered and national ones, and perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the conference is the diversity of presenters and their presentations. There are delegates from France, the USA, Switzerland, Norway and Turkey as well as the UK and Ireland in attendance. Subjects range from Egerton’s translations of the works of the Swedish author Ola Hansson and Norwegian Knut Hamsun (by Peter Sjølyst-Jackson, Stefano-Maria Evangelista and Naomi Hetherington) to her portrayals of sexuality (Rosie Miles, Anthony Patterson and Alexandra Gray) and urban identities (Sravya Raju, Jennifer Nicol and Anne-Marie Beller).

Although many scholars understandably continue to focus on Keynotes and Discords (these are the first and most famous of her volumes of short stories, and also the most readily accessible due to the fact that they are available in a modern Virago edition), there are a number of presenters who choose to focus on her more obscure output (namely, her short story collections Symphonies and Fantasias, and her sole novel, The Wheel of God). The Irish context of her work is also the subject of discussion in a fascinating paper by Eleanor Fitzsimons.

In a conference filled with excellent work not only by established academics but also by highly promising young scholars, the highlights are undoubtedly Stetz’s keynote and the roundtable discussion between Stetz, Ann Heilmann and Rosie Miles that closes the conference. Over the conference’s final hour, these three eminent and engaging women make it clear that, 124 years after her first work was published, George Egerton is still dividing opinion and encouraging debate on women’s issues and other concerns that remain not only important but relevant in both a specifically Irish and international context. Their intense personal connection to Egerton and their personal paths to finding Egerton’s work remind many of the delegates, including me, of how we ourselves first came to discover this controversial writer.

My own final discussion that weekend was with Sínead Mooney, who needs no introduction to members of the Irish Women’s Writing (1880-1910) Network. She asked me how I myself had come to discover Egerton. It was, as I’ve stated, through a volume of short stories – an anthology entitled That Kind of Woman edited by Bronte Adams and Trudi Tate – that I first encountered Egerton’s ‘The Spell of the White Elf’. But, in truth, it was James Joyce that led me there, because my purpose in reading a collection of short stories by (proto-)modernist women writers was an attempt to find at least one Irish precursor to the literary experimentation that had so blown me away when I first read Dubliners. I suppose I should have found her on her own terms, in her own space. But in reality, I backed my way into her through a male writer and his canonical work. I have a feeling that this is not at all an unusual experience.

It is to be hoped that this will not be the last conference organised on Egerton’s work, and that in the future studies will branch out to include (and embrace) her more difficult to access literary output, such as her final collection of short stories, Flies in Amber, and her experimental epistolary volume, Rosa Amorosa, which she herself considered her finest work. The ‘George Egerton and the Fin de Siècle’ conference did much to invigorate Egerton studies, and demonstrated that, even as academic work on her proliferates, there is still much more to be discovered and written about George Egerton and her texts.

Dr Whitney Standlee, University of Worcester

If you have any suggestions for the blog or would like to submit a post email Dr Deirdre Flynn

Numbers, Narratives, and New Perspectives

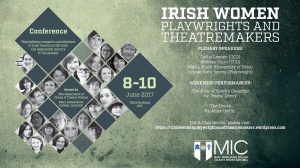

Inspirations from the ‘Irish Women Playwrights and Theatremakers’ Conference

by Dr Anna Pilz (UCC)

There was a palpable sense of historical significance in the air when activists, theatre practitioners as well as national and international scholars descended upon the Drama & Theatre Studies Department at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick for the ‘Irish Women Playwrights and Theatremakers’ (8-10 June) conference.

There was a palpable sense of historical significance in the air when activists, theatre practitioners as well as national and international scholars descended upon the Drama & Theatre Studies Department at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick for the ‘Irish Women Playwrights and Theatremakers’ (8-10 June) conference.

The three-day event was filled with stimulating papers, compelling plenaries, evocative performances, and exchanges. Appropriately and importantly, the conference had kicked off only a day after the launch of the report Gender Counts: An Analysis of Gender in Irish Theatre 2006-2015 thanks to the magnificent and relentless work of the research committee of the #WakingTheFeminists movement.

Gender Counts confirmed and revealed in black and white numbers the marginalisation of women in Irish theatre between 2006 and 2015. While the numbers speak loud and clear, the conference offered an excellent platform to enmesh quantitative analysis with qualitative research and personal experiences. In many ways, it was not only a moment to voice frustrations and call for change, but it was also a three-day recognition of women’s central contribution to Irish theatre, both at home and abroad.

Focusing on the top ten theatre organisations that receive Arts Council funding, Gender Counts highlights the astoundingly low percentage of female playwrights; only 28% of authors employed between 2006 and 2015 were women¹. How many, I wondered, Irish female playwrights were there between 1880 and 1910? Maud Gonne, Constance Markievicz, Eva Gore-Booth, Alice Milligan, Lady Gregory, and Winifred Letts come to mind. But are those representative? In 1892, the Daily Graphic noted that Irish fiction, at that moment, was ‘practically in the hands of Irish women’². Where, however, were Irish women playwrights? The 28% mentioned above only account for those who made it to the stage; but what about the percentage of plays written that were never (or rarely) encountered by a theatre audience?

There was a recognisable gap between Dr David Clare’s opening paper on Frances Sheridan, Elizabeth Griffith, Mary Balfour, and Maria Edgeworth in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and Lady Gregory’s drama in the early twentieth century. Clare productively pointed to the loss of texts by Irish women playwrights in the earlier period: texts that either never made it to publication or texts that have suffered from a subsequent neglect of scholarly editions such as the plays by Edgeworth. The identification and retrieval of such texts is important to gain a fuller understanding of women’s contribution to the dramatic tradition. And it also called to mind discussions at the inaugural conference of the ‘Irish Women Writers 1880-1910 Network’ in November 2016 where one potential initiative of the network could be in bringing works back into print via inclusion in Tramp Press’s Recovered Voices Series.

For scholarship on women’s writing, the plenaries by Dr Cathy Leeney and Dr Melissa Sihra were particularly thought-provoking in that they argued respectively for “new ways of seeing” and a “tilting of the lens” to bring to light new insights and important correctives to established narratives of literary history. Both plenaries equally stressed the importance of linking past and present, to consider points of connection and disconnection.

Leeney’s excellent plenary on “Waking up to Theatrical Aesthetics: Women’s Way of Looking”, highlighted the value of historical research in that it is an act of ‘recovery of the roots of self’; historical research assists in challenging and rejecting established narratives. Such a rejection of established narratives was most provocatively demonstrated in Sihra’s magnificent and inspired plenary titled “Beyond Token Women: Towards a Matriarchal Lineage from Lady Gregory to Marina Carr” which rendered Gregory not simply co-founder and playwright, but precursor to Synge, Beckett, Murphy and Carr in dramatic craft, language, and themes. Such levelling of the field helpfully disrupts Irish theatre history as we know it and as we find it reiterated in survey texts such as The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Theatre.

A personal highlight for me, Sihra’s historically grounded argument was poignant in many ways. For one thing, I myself had engaged in quantitative research by tallying up performances of Gregory’s plays between the opening of the Abbey in 1904 to the playwright’s death in 1932, and for the period from 1933 to 2011. Comparing the figures to performances of plays by her co-directors of the early Abbey, W.B. Yeats and J.M. Synge post Gregory’s death, I was counting from high visibility to invisibility. Yet such harsh numbers present only part of a picture that requires further unpacking. And in terms of literary history, that unpacking often requires diligent journeys into archives.

In fact, the wealth of archival research presented in numerous papers at the conference pointed to the difficulties of researching women’s lives and writings that requires creativity in sources. After all, it is not always easy to trace women within archival collections and more often than not is necessitated by a compilation of sources from birth, marriage and death certificates, letters, diaries, periodicals and newspapers. Yet hunting archival collections pays off; there was a moment of gasping astonishment and admiration for Dr Ciara O’Dowd’s scholarship on the Abbey actress and later artistic director Ria Mooney. O’Dowd discovered and revealed the effectiveness of fresh perspectives which, in this instance, resulted in a re-framing of Mooney’s work. While Mooney as a woman in Irish theatre history is associated, primarily, with the role of the prostitute Rosie Redmond in Seán O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars, as an Irish woman in a more globalized theatre world, Rooney is lauded as Assistant Director to the acclaimed Eva Le Galienne on Broadway in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

This leads to one of the over-arching threads across papers and across periods. I was struck by the repeated references to the success of Irish women playwrights on the international stage while facing rejection at home. This would seem to suggest two very different strands of narrative: one concerning women and Irish theatre which is characterised by hardship, marginalisation, and depreciation; the other about Irish women and theatre which appears to point to a rather different narrative that is filled with cultural exchange, opportunity, and success. These two narrative frameworks – women and Irish theatre versus Irish women and theatre – signal the importance of framing and point of view. Of course, this is somewhat oversimplifying a complex relationship. But to an extent, it is a question of scale and placing (Irish) women writers – of theatre or otherwise – within wider European and transnational contexts. Again, Gregory is a case in point. In a fruitful discussion with PhD candidate Justine Nakase (NUI Galway), who directed Gregory’s play Grania in 2016 (a play that was never staged during Gregory’s life-time³), it emerged that perceptions of Gregory’s stuffiness might be due to some kind of cultural blindness and national baggage that international theatre practitioners are free of. For women’s literary history more broadly, it would seem that transnational perspectives have much to offer.

If you have any suggestions for the blog or would like to submit a post email Dr Deirdre Flynn

- Brenda Donohue, Ciara O’Dowd, Tanya Dean, Ciara Murphy, Kathleen Cawley, Kate Harris, Gender Counts: An Analysis of Gender in Irish Theatre 2006-2015 (2017) p. 6.

- ‘Irish Fiction’, Daily Graphic (5 October 1891), quoted in Gifford Lewis (ed.), The Selected Letters of Somerville and Ross (London: Faber & Faber, 1989), p. 178.

- Nakase’s production of Gregory’s Grania premiered on 28 January 2016 to launch the Galway-based #wakingthefeministswest season.