WINIFRED M. LETTS (1882-1972): The Writer I Knew

Bairbre O’Hogan

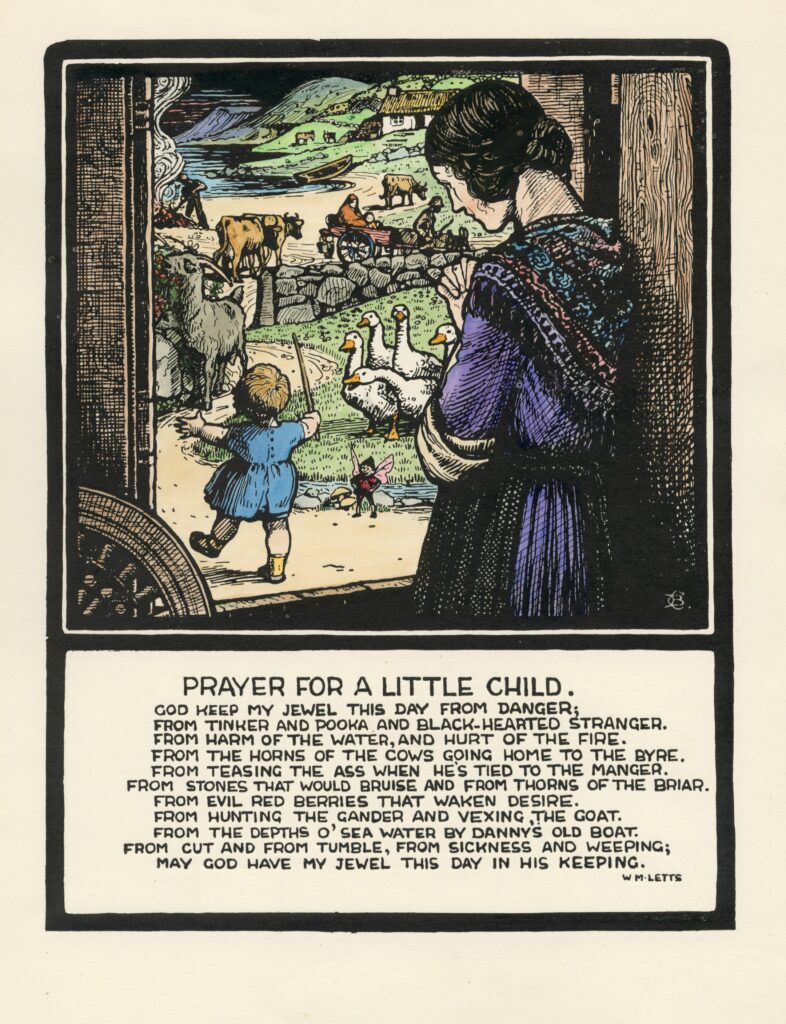

My interest in the poet, novelist, dramatist and superb children’s writer, Winifred M. Letts, is more of a personal interest than an academic one. I would like her to be rediscovered for herself – not just to claim a stake in literary history, nor to feature in an anthology, but to be remembered for so many facets of her life including, of course, her ground-breaking war poetry, the acclaim her BBC-broadcasted children’s stories won, her status as one of the few women to have had more than one play performed in the Abbey Theatre (kindly drawn to my attention by Shirley-Anne Godfrey of the University of Galway), her beautifully produced religious picture books, her charitable works, the insights into the lives of children, both privileged and underprivileged, which her writings display, her kindness and mentoring, and her strong belief in women and in feminism – a term, incidentally, which she herself used as far back as 1928, when writing for the Commonweal magazine, in relation to Saint Hilda and St Brigit.[1]

Mid-1960s, primary school holidays, Thursday mornings – my mother and I would collect Mrs V., as I knew her (her married name of Verschoyle was quite a mouthful for a small girl), from her beautiful cottage on Ballinclea Road, Killiney, to bring her to do her shopping in Dún Laoghaire. She would have been in her early eighties at this time. On our return to Beech Cottage, the first task was to open the kitchen window to allow a lame robin, whom she named Steptoe, to hop in onto the windowsill to peck at crumbs. I was left to entertain myself while my mother helped her to put away the shopping. I’d browse her bookshelves, filled with her own works and those of her friends and contemporaries – the likes of Patricia Lynch, Pádraic Colum, Lennox Robinson, J. M. Synge, W. B. Yeats, and Lady Gregory – or I might wander around the beautifully fragrant back garden which she shared with the neighbouring cottages. Winifred loved all flowers – wild and cultivated – and the garden attracted butterflies and bees, and – it seemed to me – sunshine.

Another activity I associate with Winifred was collecting large print books for her from Dún Laoghaire Library on a Saturday morning. It was no extra burden on us, as my father and I frequented the library that day anyway. We would often also bring new batteries for the small transistor radio which gave her so much pleasure and companionship. And when she eventually moved to a nursing home ca. 1969, my parents would collect her for a Sunday drive and bring her to those places in the Dublin and Wicklow mountains – Kilmashogue, Glencree, Glenasmole and so on – which had meant so much to her.

The friendship between my mother and Winifred stemmed from Winifred’s marriage in 1926 to William H.F. Verschoyle, a widower whose first wife had died of a broken heart, it was said, following the deaths of two of her three sons in WWI: Francis had been killed at Ypres in 1915 and (William) Arthur, whose body was never recovered, died at Arras in 1917. While Mr Verschoyle was inspecting his lands at weekends in the company of my grandfather, who was employed as Steward of the Verschoyle Estate, Winifred would spend the afternoon in my grandmother’s kitchen, revelling in the company of the seven children. She took a particular interest in my mother and their friendship continued for almost fifty years.

Christmas 1967, the postman delivered an autographed copy of The Turfcutter’s Donkey Kicks Up His Heels, sent to me by Patricia Lynch at Winifred’s request. That book is still on my own bookshelf, along with various books that she gave my mother and me, including her own mother’s first edition copy of Songs from Leinster, her first book of poetry which was published in 1913, and a first edition copy of More Songs from Leinster, which the newly-remarried W. H. F. Verschoyle gave to my grandfather when it was published in 1926. Alongside those is a well-thumbed copy of Knockmaroon, her 1933 book of memoirs, which includes the essay ‘Demeter’s children’ – all about my mother’s family.

https://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cuala_prints/18

Glancing back over Winifred’s life, it is clear that she was always a strong, independent woman – at sixteen, she moved from an English midlands boarding school to Dublin to attend Alexandra College, the first women’s college in Ireland; she went to the Abbey Theatre even though her family wouldn’t have approved; in 1915, she began working in a Manchester hospital as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse and later qualified as a masseuse and worked in various military hospitals in England and Ireland. And although she loved her husband W. H. F. dearly, she found domestic life in their city home on Fitzwilliam Square somewhat stifling – where blinds had to be kept half closed for decorum, and cooks and house parlour maids had to be employed and managed. Her ‘Rhymes of Domestic Prose’, published in Punch in 1930, reflect those constraints:

Revolt

“I will arise and go now” – but not to Innisfree

For I should have no peace there from domesticity.

I’d rather see my luggage in some well-run hotel

Where I might lounge at leisure and freely ring the bell.

And oh! The meals I’ll have there in glorious surprise

Not yesterday’s boiled mutton recooked in some disguise.

And no-one will upbraid me because the meat is tough

And no fears will assail me that there is not enough.

I shall not as a duty look out for moth and rust

Or run a blameful finger across a plane of dust.

I will not slack the fire nor count the cost of coal,

For ease of mind and body shall be my chosen goal.

“I will arise and go now” – but where you may not guess;

So mind the house, dear husband; I’m leaving no address. [2]

But my reminiscences alone aren’t sufficient to bring Winifred back from the shadows. Her war poetry brought her some recognition during the centennial commemorations of WWI and poems such as ‘The Deserter’ and ‘Screens’ were featured in new anthologies. But her books are out of print, and her novels and children’s books are perhaps too much of their particular time to be sought out again by general audiences, though they remain of interest for academic purposes. Only Letts’ poetry continues to attract interest. However, I have gained great enjoyment and satisfaction from my search – mainly online – for her published essays and stories and poems, stretching as far back as 1904. And equally satisfying is my success in tracing – after many years of queries and quests – the soldier about whom she wrote ‘To A Soldier in Hospital’ and who she identified only as A.W., and the young boy who was reluctant to go to school, about whom she wrote two poems. I have been able to share these poems with their children and grandchildren. University libraries have been another great source of material for my research, as many of Winifred’s letters to publishers, editors and other authors are preserved in their collections. The difficulty here, of course, is the charge levied by many universities for access and copies, though I have been very lucky to come across a few extremely generous librarians and staff members who have set aside, or have reduced, charges for me, on the basis that I do not have academic funding.

Sadly, when Winifred, in her late eighties, was moving out of her home to a nursing home, no plan was in place to preserve her papers. I am very appreciative of her great-niece’s kindness and generosity in allowing me to access the material she has managed to gather, and most importantly, for encouraging me to put on record – for future generations – the Winifred M. Letts I knew.

With thanks to Mrs Oriana Conner, great-niece of Winifred Letts, for sharing her family photographs and giving permission to publish.

[1] Letts, W.M. (1928) ‘The Holy Well’, The Commonweal 9(2) p.45

[2] Letts, W.M. (1930) ‘The Revolt’, Punch (178) p.400

BAIRBRE O’HOGAN

researchingwmletts@gmail.com

Excellent article. I’ve come across one newspaper feature written by Winifred.

It’s the Spectator 11-04-1931

Do not know if it is part of a bigger work or a stand alone piece. Either way, you may not be aware of it.

Many thanks

Pingback: Cuala Press Print – The Museum of Childhood Ireland