Emerging Voices 1: Nora Moroney

Nora Moroney

Nora Moroney has a research specialism in Irish literary cultures and their influence on and connection with the late-Victorian British periodical press. Her publications to date include articles on Irish women journalists in the Victorian Periodicals Review, focusing particularly on the writings of Alice Stopford Green and Charlotte Grace O’Brien, and on Belfast newspapers in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Volume 3. Funded by the Irish Research Council Enterprise Partnership Scheme, she is currently conducting research into ‘The Benjamin Iveagh Library: A Cultural History of Collecting in Twentieth-Century Ireland’, a project that focuses on a private book collection based at Dublin’s Farmleigh House in Phoenix Park. Prior to her IRC postdoc, Moroney held a research post in the Manuscript Department of the National Library of Ireland where she worked on collections of nineteenth-century estate papers and twentieth-century literary archives.

Q: We’re curious to hear about your research journey. What brought Irish women’s writing into focus for you? What particular experiences, what texts, what moments of recognition of gaps and elisions in our existing knowledge inspired you to pursue the types of reclamation efforts you have been and continue to be involved in?

NM: I came to women’s writing through studying alternative modes of publishing. I remember being introduced to Emily Lawless during my undergraduate dissertation, and being totally enthralled by her work. Like many other women at the turn of the century, she was an astute user of the periodical press to advance her career. She had such fascinating and contradictory standpoints in her articles, from being part of a cosy old boys club featuring W.E.H. Lecky and William Gladstone, to eulogising about the sea creatures of Ireland’s west coast. She also staunchly resisted any efforts to define and categorise her. Through this, I also learnt the value of moving beyond acts of reclamation to viewing women writers in light of their ‘hybridity’, in J.W. Foster’s term – or what might be called intersectional influences of class, race and gender. Writing these figures back into the political and literary discourse of the day became a key object of my research, as well as an enjoyable archival pursuit.

Q: For your PhD, you examined the contribution of Irish writers to the British periodical press. What questions drove your research and where did Irish women writers and journalists enter your investigation?

NM: For my doctoral work I decided to expand my research to include a larger range of Irish writers who worked for the British periodical press from 1880 to 1900. I deliberately kept my focus as broad as possible in order to find a representative snapshot of such writers (journalists, you could also call them, though this would have rankled with many who saw their work exclusively in the realm of literature and philosophy and far away from the hack work of Fleet Street). From there, I started to investigate other women who were part of these loose networks of the high-brow press, figures such as Alice Stopford Green, Charlotte Grace O’Brien and Hannah Lynch. My thesis ended up with a 50-50 split between women and men, looking at fiction and non-fiction writings across four major journals. My findings? Irish women (and men) were involved at every level of British cultural, political and intellectual commentary, helping to shape questions of national and international import at a crucial juncture in the relationship between the two islands.

Q: What surprised you about the Irish women journalists that you encountered through this research and what avenues for future work has it opened up?

NM: I think the sheer variety of subjects that women writers grappled with was one of the most surprising aspects of my research. Thanks to pioneering work from Heidi Hansson, Elke D’hoker, Kathryn Laing and others, I had expected to find their imprint in the development of the short story, New Woman thought and fin-de-siècle salon culture. But I also encountered their work in the fields of political and social activism, overseas commentary and literary reviews.

Many of them also moved fluidly between fiction and non-fiction in their periodical output, opening up many unexplored avenues of research and challenging us to consider the generic boundaries we place on women’s writing.

Charlotte Grace O’Brien, for instance, wrote politically-inspired poetry while campaigning for women’s protection on transatlantic ships, while Alice Stopford Green combined a nascent historical nationalism with insightful journalism on the Boer War. They capitalised upon the ready-made networks which periodicals provided, enabling them to move among dynamic publishing circles in London that are ripe for further excavation.

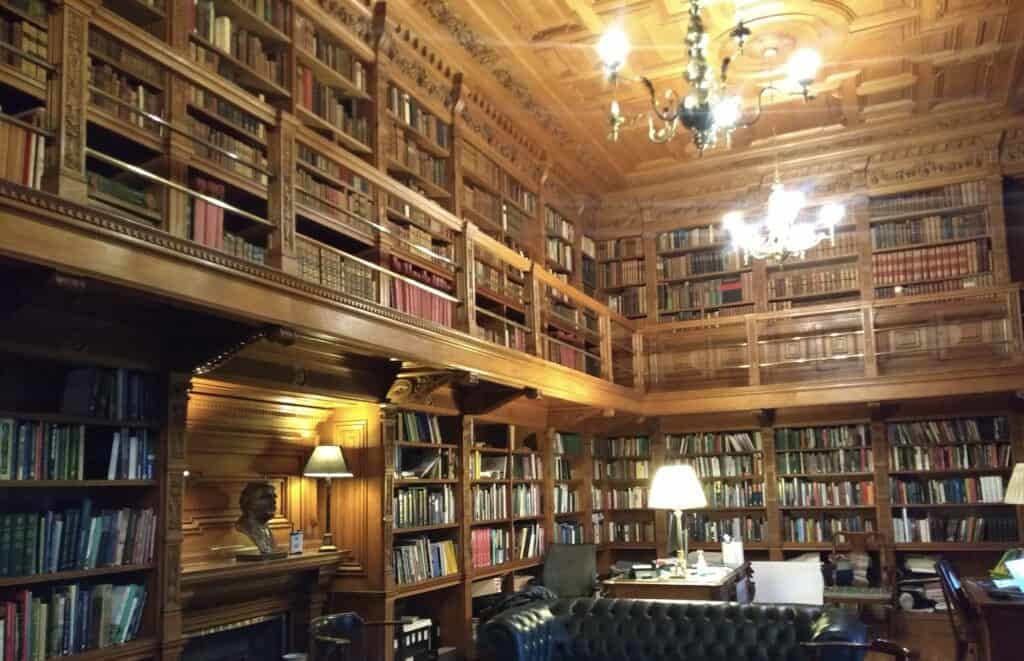

Q: Your work is focused primarily on archival research and continues to make significant contributions to our understanding of Irish book history. Currently, you are working on a cultural history of the Benjamin Iveagh Library at Farmleigh House, one of Ireland’s most well-preserved Big House libraries. With over 5000 items, the collection includes both printed and manuscript materials. Tell us a bit about this particular private book collection. What is your sense of the collection to date and what set of questions do you bring to it?

NM: Benjamin Guinness, the third Earl of Iveagh, was one of the great book collectors of twentieth-century Ireland. Between 1967 and 1992 he built up a collection of Irish-related material, featuring first editions of almost all major authors, fine book bindings and rare manuscripts. The quality and attention to detail that underpins the collection is outstanding – most of the books are in superb condition, chosen for their significance to Irish literature, history, science and theology. Alongside first editions of Swift, Edgeworth, Wilde, Yeats and Heaney, we find almost all of Robert Boyle’s printed works, the entire oeuvre of Somerville and Ross and the first translation of the Bible into Irish. I aim to contextualise the library in terms of collecting and reading practices in twentieth-century Ireland, and to address broader questions around the culture and perceptions of big house life in an era following the Civil War.

Farmleigh House

The collection is a joy to work with, and throws up new surprises every day. For instance, I recently came across an intricately detailed, illustrated German bible in an eighteenth-century Irish binding – a great thrill of serendipity. The tactile and visual pleasures of working with such a library have reinforced the importance of books for me, especially at a time when we’re all so reliant on the digital and the electronic. I hope the project will ultimately bring the collection to a wider consciousness and enhance appreciation of our extraordinary printed heritage.

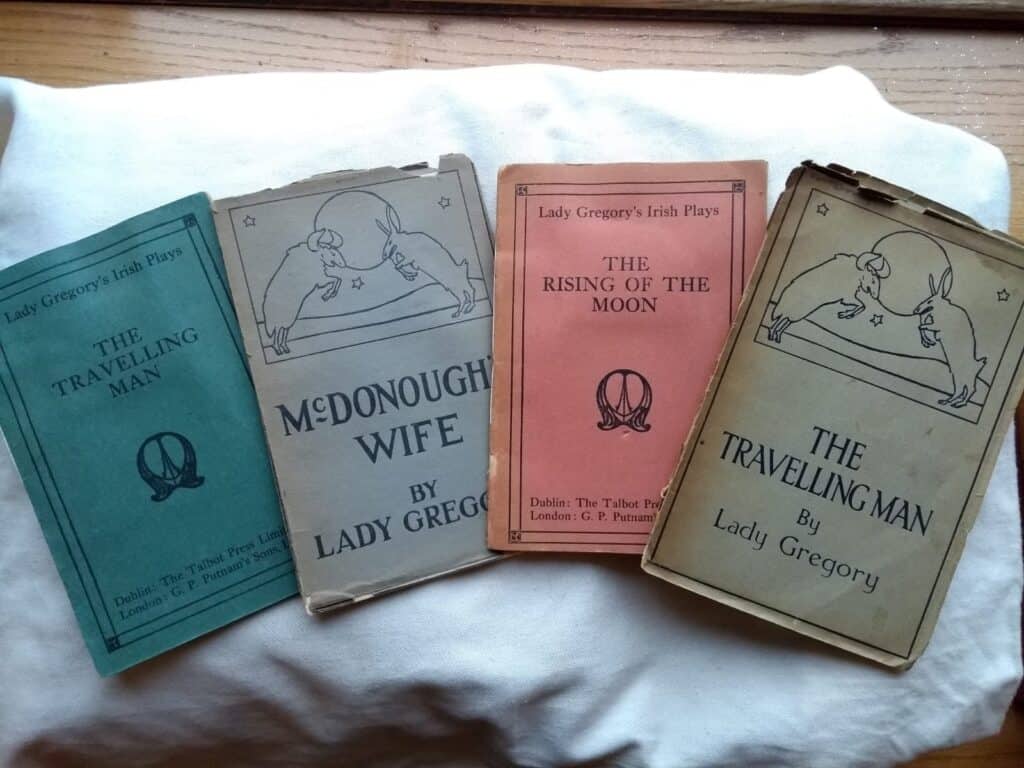

Q: For some genres – such as dramatic texts or manuscripts of short stories or essays, for instance – no hard copies survive in archives. Consequently, our perception of Irish women’s literary history is fragmented in some ways. Private collections such as the one at Farmleigh offer a rich window into the circulation of cultural productions, interests, and networks. In what ways do you bring the question of gender into your current project?

NM: I’ve tried to incorporate questions of gender and representation into this project from the outset. At first glance, very few women occur in the collection (I’ve found eight in total), a signal of the regard in which women’s writing was held up until recent decades. Questions of value occur here too – Iveagh consciously sought out the most exquisite and deluxe editions, a field in which women were rarely well represented. But digging beneath the surface reveals some interesting moments of female participation that are not always inscribed on the cover of a book. There is a significant collection, for example, of Cuala and Dun Emer Press productions, the publishing houses run almost exclusively by women. Iveagh seems to have had a particular interest in Somerville and Ross as well, purchasing several valuable manuscripts of their work including a draft notebook of ‘Irish Memories’. Meanwhile, the Lennox Robinson collection of papers and correspondence contains many letters from leading Irish women writers, showing how women’s voices and networks do emerge from this collection. By paying attention to the margins – literally – we can trace their influence across Ireland’s literary history as embodied in the library.

Q: In many ways, being able to dive into a private library collection is any book lover’s and literary historian’s dream. Is there an item or a particular discovery that stands out in shaping your approach to the collection?

NM: For me, one of the most interesting discoveries has been the ephemera and marginalia that peppers the collection. Many of the books here proudly display their provenance through signatures, inscriptions, coats of arms and bookplates, and you can happily waste many hours tracing the (sometimes very illustrious) former owners. These include – perhaps unsurprisingly – many aristocratic patrons and collectors from across Ireland, Britain and Europe, such as Shane Leslie of Glaslough, the Duke of Devonshire and Catharine de Courlande, god-daughter of Catherine the Great. Personal and ownership history, of course, is an important aspect of a project like this, providing an insight into the lifecycles of books and printed material over centuries. It also humanises the collection, allowing us to understand why books were given, purchased and cherished. One letter, inscribed in the front leaf of Lady Gregory’s presentation copy of The Kiltartan History Book for the painter Augustus John, reads ‘just to remind you of Galway, where I hope you will return and paint other such beautiful pictures as that one in the Tate’. By attending to an entire collection, and not just a narrow research question, I’m lucky to have the opportunity to indulge in these stories and personal histories.

Q: No doubt there is great depth and richness to the materiality of the collection as well as its diverse content. In the past, you’ve held an ICHS Research Studentship at the National Library of Ireland, where you were involved in a small exhibition on the Kate O’Brien papers. At the time of this interview, the Covid-19 pandemic has put many exhibitions and initiatives on hold. Looking ahead in hope, though: do you have plans to invite a wider audience to engage with the collection?

NM: It’s one of the many ways research has been affected over the last year, effectively shutting down all public access to archives and libraries. I had initially envisioned a series of show-and-tells at Farmleigh House over the summer, along with rolling exhibitions and engagement with the local community. With any luck this will be possible in the future – I really want to bring people into the library itself, and open up the space for public appreciation. It’s such a beautiful room, built especially for these books in a double-height oak, that I feel it can only be truly appreciated by experiencing it in person. The same can be said for the material: the vital sensory allure of exquisite old books and bindings is one that is very hard to convey through words or images. Nevertheless, I have published some blog posts on RTE Culture and the Farmleigh website that I hope gives a taste of the treasures within the collection. I’m also indebted to Marsh’s Library (who own the collection) and their engaging and lively social media presence which does a great job in highlighting the strange, funny and unique features of rare book scholarship – not always the easiest of tasks!

Q: What new discoveries – of ideas, achievements, experiments, thematic concerns, etc. – is your research bringing to light?

NM: I hope that this research will feed into a growing understanding of the significance of book and publishing history in an Irish context. Specifically, the role of book collecting in the shaping and preservation of cultural heritage is something that has largely flown under the radar in critical scholarship. As the backbone of many of our institutional and academic libraries, private collections have had a considerable role in how archival research has developed in Ireland. A more thorough interrogation of the underpinning structures is something that is badly needed. In my own work, for example, I look at what a Protestant Irish patriotism invested in 18th-century Irish print culture and 20th-century modernist literature signifies in ideological terms. By framing it within these kinds of wider contexts, the publishing achievements of Irish writers, historians and scientists can be examined in fresh light.

I hope too that this research will help focus attention on the importance of our national collections, and the continuing work that needs to be done on preserving, expanding and diversifying access to areas commonly perceived as being dry and dusty. The sheer amount of imagination, wit, invention and polemic contained within even a small collection such as the Iveagh Library is mind-boggling. I only wish I had time to read it all!