Emerging Voices 4: Isobel Sigley

Isobel Sigley is currently undertaking a research studentship at Loughborough University, supervised by Dr Sarah Parker and Dr Claire O’Callaghan. Her research considers women’s short fiction from the late nineteenth century through to the early twentieth century and explores the ways in which touch, or the haptic senses more broadly, serves the politicised agendas of the ‘New Woman’ movement. She investigates the affinity between the active and agentic sense of touch and the search for agency and emancipation for late-Victorian women in literature. The Irish ‘New Woman’ authors George Egerton and Sarah Grand feature centrally in this research.

Her most recent publication is the article ‘Engendering New Motherhood: Tactile Exchange in George Egerton’s Keynotes (1893) and Flies in Amber (1905)’ published in Victorian Popular Fictions Journal in July of 2021. This article addresses the shortage of scholarship on Egerton’s later writing by assessing the consistency with which Egerton invokes moments of touch and object exchange as means to radicalise motherhood in two popular and well-known early stories, “A Cross Line” and “The Spell of the White Elf” (Keynotes), and a less-known later story “Mammy” (Flies in Amber). In this revisionist reading of Egerton’s work, Sigley argues that understanding Egerton’s valorisation of maternity as a “New Motherhood” challenges claims of essentialism and accusations of conventionality in Egerton’s writing.

She is currently in the early stages of co-editing a volume of essays on the work of George Egerton with Dr Whitney Standlee.

This is the fourth interview in the emerging voices series which aims to showcase and promote the work of current doctoral students and/or early career researchers who are working in the field of Irish women’s writing in the period between 1880 and 1920.

Q: Although your research is not focused specifically on Irish women writers, the writings of two Irish women, George Egerton and Sarah Grand, have emerged as central to your doctoral study. When you first discovered them, what about these writers and their works struck you as unique and of particular interest?

IS: My interest in Egerton was sparked by her short story ‘Wedlock’ which I read as part of an undergraduate module on New Woman Writing convened by Dr Anne-Marie Beller. I found Egerton’s ability to address the Woman Question from a different class perspective, with a lower-class protagonist, and through a dark narrative, as the protagonist grieves the loss of her estranged daughter, especially unique. The New Woman is more often than not a middle-class figure; Egerton’s revision of this trope to address a wider breadth of womanhood stood out. In contrast to the perhaps more pithy, upbeat narratives of wealthy, mobile middle-class heroines, ‘Wedlock’ made me pause and take the New Woman movement seriously.

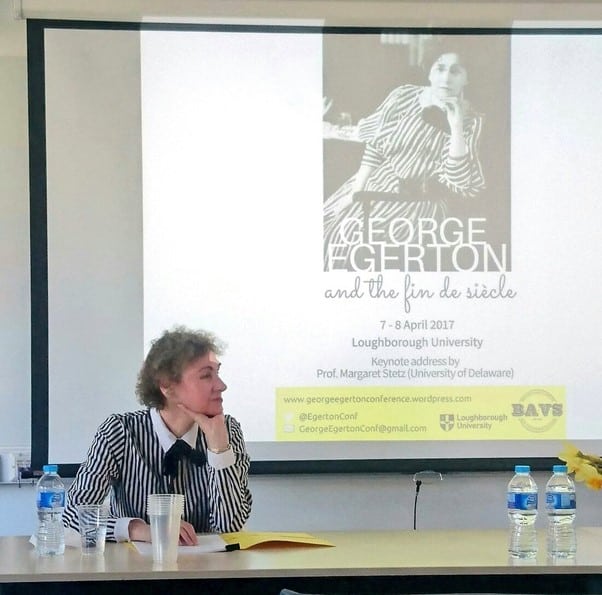

Professor Margaret Stetz (dressed as George Egerton) giving her Keynote Address at the ‘George Egerton and the fin de siècle’ Conference, Loughborough University (April 2017)

I have to also thank Professor Margaret Stetz for her keynote at the ‘George Egerton and the fin de siècle’ conference at Loughborough in 2017. The semester after taking Anne-Marie’s module, I was lucky enough to attend the first international conference dedicated to the life and work of Egerton, where some real academic A-listers gathered (seemingly on my doorstep!). Stetz’s entertaining and impassioned keynote (not to mention her sartorial homage to Egerton) couldn’t have been a better advertisement for Egerton’s endlessly fascinating writing and mightily complex personality.

For Grand, it was her theatrics. I remember attending one of Anne-Marie’s lectures, which began with the brief biographical detail of Frances McFall’s reinvention as Madame Sarah Grand. I thought it was fabulous! Her short fiction also struck me as quite high tempo and almost climactic as she exposes the double standards of the patriarchal society – as Josepha imposes herself boldly on the titular ‘Man in the Scented Coat’ at the clandestine club while adventuring through the famous London fog, or as the model bosses the struggling artist around before leaving him high and dry in ‘The Undefinable’.

In my thesis, it is Grand’s last volume of short fiction, Variety, published in 1922 that interests me, as it contains two debuting stories that reprise Josepha, an earlier protagonist of Grand’s, decades after her first appearance, and after the New Woman movement had (supposedly) dissipated. These stories take a surprising shift towards the supernatural, an interesting diversion for a writer whose novels were staunchly realist. These stories help to address one of my core research questions surrounding the ‘death’ of the New Woman; I argue that it is really only in name that the New Woman phenomenon faded from existence and that the challenge to society that she spearheaded lived on in new forms (and in Grand’s case, new genres).

Q: The decision to focus on touch/the tactile in women’s short fiction is intriguing. Where did that interest arise from and can you explain briefly why you find the portrayal of touch and the haptic senses integral to understanding the work of writers such as Egerton and Grand?

Cultural Historian Constance Classen’s edited collection on touch.

IS: I was struck by the prominence of hands and feet in Egerton’s short fiction. For example, the foot massage in ‘A Cross Line’ from Keynotes (1893), echoed in the fetishism of ‘A Nocturne’s narrator from Symphonies (1897), and the emphasis on pretty hands in ‘Now Spring Has Come’ (Keynotes). It was not until I encountered Kate Chopin’s brilliant short story ‘A Pair of Silk Stockings’ (published in Vogue in 1897) that I realised there was a wider trend of significant bodily sensations throughout many first-wave feminist short stories. I wrote a blogpost for BAVS’ The Victorianist about Chopin’s story: See here.

It occurred to me (after spending months in the company of Constance Classen’s work on the senses, Iris Marion Young’s feminist phenomenology, and Mark Paterson’s interdisciplinary writing on touch) that there were certain parallels between the New Woman’s search for independence/agency/autonomy and the subjectivity of haptic experience, as it facilitates active embodied involvement. Since beginning my PhD, I have grappled with how to define or describe this affiliation between the properties of haptics and feminism. I have recently begun to think of touch as a kind of praxis for the New Woman’s grasping for emancipation, but it’s an ongoing battle and I don’t think I will settle on which terms to use until it comes to finally submitting!

This praxis plays out most significantly in Egerton’s work through her characters’ exchanges with one another, as the mutual haptic experience provides a space for the radical and anti-patriarchal negotiation of relationships. A clear example of this is the very opening scene of ‘A Cross Line’ when Egerton’s protagonist meets a man by the river where she fishes. She scrutinises his book of fly, flicking past certain pages and dwelling admiringly on others, exhibiting her authoritative knowledge of fishing. Through her haptics, she flips the patriarchal hierarchy on its head, usurping the dominant and superior role. After he crosses a line with his flirtations, she unceremoniously hands back his book, ending the exchange abruptly and demonstrating her autonomy. In my mind, haptics are crucial to understanding the gender politics within this scene.

Q: Congratulations on the publication of your article! It’s wonderful to see your doctoral research already making an intervention. You argue in it that the claims (or accusations) of gendered essentialism and conventionality often levelled at Egerton by earlier scholars have failed to consider how Egerton’s work reconceptualises motherhood and, in doing so, constructs models of ‘New Motherhood’ that radically redefine the maternal. Can you tell us more about this?

IS: Thank you! I am really excited to have published on Egerton and motherhood. I suspect that there’s a tendency to view motherhood as a more boring topic of discussion compared to the more risqué and/or decadent writings produced by Egerton and her contemporaries, but hopefully this article goes some way towards showcasing the richly radical side of motherhood.

Earlier scholars have accused the conclusions of ‘A Cross Line’ and ‘The Spell of the White Elf’ – both involving the protagonists’ acceptance of a maternal role – as demonstrating Egerton’s lack of feminist conviction and her (allegedly) essentialist view that all women should succumb to their so-called maternal instinct, thereby suggesting her complicity with patriarchal convention. My article seeks to offer an alternative view that reconciles Egerton’s maternal conclusions with her otherwise celebrated feminist philosophies. ‘New Motherhood’ is hence a term I use to demonstrate the marriage of Egerton’s radical ‘New Woman’ ideas with motherhood in a way that maintains her characters’ resistance to patriarchal convention even as they align with the (typically traditional) maternal role. For example, Egerton’s New Mothers sometimes swap the mother’s typical domesticity for the husband’s public professional role, allowing them to sustain their New Woman’s financial independence; they exhibit a lack of maternal instinct (but their male counterparts are shown to be nurturing), showing that not all mothers are the same and that motherhood is not an easy or essentialised experience; and they promote alternative forms of mothering, such as adoption, that are not in keeping with convention. Lastly, the maternal qualities that Egerton’s New Mothers exhibit are often directed towards other women in crisis, not children. Through this, she reconceptualises motherhood as something that promotes solidarity among women, often across class divides, in their shared or mutual struggles against patriarchal systems.

Just to add – I had a great experience with the editors of the Victorian Popular Fictions Journal, who took the time to demystify the process and encouraged me to turn a conference paper into a publishable article. There are many horror stories about publishing in academia but the VPFJ made it a painless and rewarding experience, with encouraging reviewer feedback. The article is also open access, so anyone can read for free.

Q: Egerton and Grand have very different connections to Ireland. Egerton was born to an Irish father and Welsh mother and identified herself as Irish; Grand was born to British parents while living in Ireland, where she remained for only the first eight years of her life. But both experienced uprooting and migration during their childhoods, and both spent the vast majority of their lives living outside of Ireland. To what extent (if any) is the divided position of the migrant – to paraphrase Salman Rushdie, of alternately feeling either that you straddle two cultures or fall between two stools – evident in their works? Does this same position inform the challenges to conventionality that both writers enact[ed] in their fiction and/or in their lives?

IS: My undergraduate dissertation focused on Egerton’s use of liminality, and I believe that her liminal nationality certainly informed her fruitful use of in-between states to represent the insecure status of late-nineteenth century women. Twilight, dawn, and/or spring are particularly pregnant times in Egerton’s fiction; not to mention the liminal state of pregnancy, too! The sense that Egerton was never able to wholly identify or relate to a demographic – whether that’s the Irish or the New Women writers with whom she is often grouped, or the modernists she is credited as “anticipating” – makes it such a tricky task to define or pigeon-hole her. Herein lies the cultural value of her work: it speaks to many adjacent and concurrent issues at once. Egerton sits in the centre of a very complex Venn diagram!

Sarah Grand by Elliot & Fry, in Cassell’s universal portrait gallery: A collection of celebrities, English and foreign with fac-simile autographs, 1895, https://archive.org/details/cassellsuniversa00londiala/page/118/mode/2up

Grand’s sense of national instability makes me think of Josepha, the character who resurfaces in her late collection Variety in 1922. Across the three stories in which she appears, Josepha has several temporary homes – a townhouse, a top-floor London flat, a dilapidated eighteenth-century rented property. Josepha also variously cycles, drives a motorcar, and travels by train. Her mobility is a striking and consistent aspect of her character and may be a quality that Grand appreciated from her own experience of migration. Josepha is a fiercely independent character who doesn’t stay rooted, but the fact that she stayed with Grand for two decades might be suggestive of her continued relevance.

Q: Were either of these women involved in women’s networks and networking? And have you found similar connections important to your own work as a writer and researcher?

IS: Egerton’s literary networks seem to be dominated by men. She was strongly attached the men at The Bodley Head, with John Lane being a close friend and staunch supporter of her writing until the late nineties. Richard Le Gallienne is another important figure in Egerton’s network, but I can’t say that I am aware of her having any involvement with women’s networks. I would be happy to learn otherwise! She was not particularly fond of the other ‘New Woman’ writers, though she has since been somewhat canonised as a New Woman Writer herself, and as a notoriously prickly figure, I suspect not many found in her a warm and inviting peer. This is nevertheless something she perhaps lacked, which may be why I identify an appetite for female friendship (or a maternal network, as I call it in my article) in her short fiction. Her heroines often confide in other women, who take comfort in one another where possible.

It is widely known that Grand was heavily influenced by Josephine Butler’s campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts and she was a member of the Women Writers Suffrage Association. Her short fiction, in contrast to Egerton’s, nevertheless often follows women’s solitary moments. Indeed, ‘A New Sensation’ (1899) shows Grand’s protagonist tiring of her network of friends and leaving for the countryside alone to seek a new experience in a “lovely lonely land”.

For my own work as a researcher, I feel blessed to have supervisors who so openly share their networks with me. My supervisor Sarah took the initiative to ask around her network about the George Egerton edited volume and put my name forth in discussions to revitalise the project. From this, the opportunity to work with Whitney on the volume arose and I’m immensely grateful and excited about it all! For early careers researchers, having a network with established scholars who are eager to help the next generation is enormously important.

Q: Your research analyses Grand’s and Egerton’s texts alongside that of more well-known women writers such as Kate Chopin, Katherine Mansfield, Jean Rhys, and Vernon Lee. For those of us centrally involved in raising the profile of Irish women writers, your study fruitfully opens out to a transnational approach that is more concerned with a thematic focus on a particular time period than with the more common attention to questions of national identity and national politics. How and why have you come to group these women and their work together?

IS: It is vital for my thesis to substantiate its claim that the tactile is a prevalent theme throughout turn-of-the-century women’s short fiction, and the obvious way to do that, in my mind, has always been to draw from a wide range of writers. As such, I attempt to ground my thinking in the works of writers more securely associated with first-wave feminist or New Woman movements, through the likes of Egerton and Grand, but then go on to expand my pool of writers to show the versatility and ubiquity of the tactile. Since I am arguing that the tactile is a kind of praxis for New Woman values (more so than exclusively for the New Woman figure or stereotype), it is important to show where the tactile occurs alongside these same values beyond the niche of the New Woman. This involves looking beyond Britain, beyond the 1890s, beyond whiteness, beyond Victorianism. I have recently drafted a chapter on Kate Chopin’s and Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s New Orleans stories, for example, which employ tactility in discussions of intersectional oppression. In turn-of-the-century spaces where matters of autonomy, agency, and independence are questioned along gendered lines, I expect to find a deliberate rendering of tactility.

Q: It seems to us that there is something really interesting about the ways in which Irish literary scholarship has been concerned with ‘claiming’ women writers and in the arguments that have arisen around issues of inclusion and exclusion to and from the canon. For different reasons, some Irish women writers have been given less prominence within Irish literary criticism than others: the works of Maria Edgeworth and Elizabeth Bowen, for example, have long been included on course syllabi and have been the focus of academic research both in and beyond Ireland, while Egerton’s and Grand’s texts have begun only very recently and very gradually to appear on undergraduate reading lists. Would you situate your work within these reclamation efforts, or are questions of literary value irrelevant to your work?

IS: With both Egerton and Grand, I am very much in the game of reappraising their later and lesser-known works. Egerton’s final volume of short fiction, Flies in Amber (1904), and Grand’s Variety (1922) have been largely neglected by any reclamation efforts. Neither collection was received upon publication as well as their previous works had been during the supposed ‘heyday’ of New Woman fiction. But rather than accepting the impressions we inherit from contemporary reviewers and dissemination, critics today can gain a lot of insight from these final collections. I believe there is a resilience to them, brought out into the world at a time when there was only waning (if any) appetite for works by writers so constitutive of a previous century. What narratives did Egerton and Grand manage to push through to publication in these final collections? The mere fact that they did make it into the public domain must therefore imbue them with a certain amount of literary value, when it would have been easy for publishers to reject them as the writings of literary ‘has-beens’.

My first conference paper, ‘‘A Place of Possibilities’: The Temporal and Spatial Escapes in George Egerton’s ‘A Cross Line’ for Breaking Bounds PGR Conference, Portsmouth University, 2019.

In regards to Irish literary criticism, looking at the Irishness of Egerton’s writing is undoubtedly a fruitful approach to understanding her fiction’s complexities, therefore her inclusion on courses of Irish literature would encourage many fascinating developments within Egerton studies. And, I believe, vice versa; Egerton would enrich studies of Irish literature if she were included. Her stories contain many delineations of her conflict with Ireland and the culture she grew up with. Likewise, there is a complex relationship between the city and the countryside in Grand’s writing, often expressing a desire to get away from London for a while. This romanticisation of the rural might be of interest to scholars of Irish literature, set up potentially as the antithesis to the increasingly urban metropolis and a symptom of Grand’s nostalgia.

Q: On a related note, your grouping of women writers begs another question: is the Irishness of these authors significant to you in terms of your own research? And more generally, how useful are these types of cultural/national categories? Do they open up and extend our explorations or do they tend instead to limit them?

IS: I wouldn’t want to dismiss or erase their Irishness. For Egerton especially, it is a very core aspect of her identity and manifests in her fiction in many varied ways, both implicitly and explicitly, with positive and not so positive renderings. Her Irishness is always there in my considerations of her writing, but it is not my main approach to her stories, at least at the moment.

It is useful to think of national categories in order to delineate what unites across or permeates the borders; for me, that is a shared awareness of the empowering properties of tactility. In that sense, I think these cultural/national categories can be productive parameters, useful to define the scope of a project or to bring about interesting connections and parallels, opening up and extending our explorations and/or limiting our explorations according to how and why we employ them. I guess that’s a very diplomatic answer!

Q: Beyond your own current project, what potential future research areas/interests have you identified in Egerton’s and Grand’s work? And do you have any particular advice to give students and researchers new to the study of these women’s works?

IS: I think generally there is a lot more to discuss about Grand’s short fiction. Her novels have dominated scholarship and built her up as at times insufferably didactic. Her short fiction is more experimental and quite accessible (they work well to introduce undergraduates to the themes of the 1890s woman’s movement.) An anthology of her short stories is surely on the cards. Ironically, for Egerton it is somewhat the reverse – her early short fiction, Keynotes and Discords, has dominated scholarship, while her novels such as the epistolary Rosa Amorosa have been rather left on the shelf.

I would be interested to work on something about ill-health and ageing in Egerton’s writing and how her sympathetic portrayals of sickness might add nuance to the accusations of eugenicism levelled at her. She was herself something of a hypochondriac, so it would be fascinating to see whether this played into her fiction.

My advice to anyone approaching Egerton’s or Grand’s writing for the first time would be to keep an open mind, pay attention to the nuances, and appreciate the lighter moments of their oeuvre as well as the heavier material. Both constructed characters that we shouldn’t always take at face value.