Emerging Voices 3: Tara Giddens

Tara Giddens’ PhD project, ‘Investigating the Irish New Woman: Journalists in Media and Fiction’, offers exciting new research into Irish women’s contributions to popular culture and journalism. Focusing on the journalistic and literary careers of Kathleen Coleman, Charlotte O’Conor Eccles and L. T. Meade, her doctoral work was supervised by Dr Tina O’Toole and supported by an Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences PhD Teaching Fellowship at the University of Limerick.

Originally from the United States, she received a BA in English at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington and worked as a professional journalist between 2009 and 2012. In 2014, Giddens moved to Ireland to further her studies and received an MA in Irish Literature at Maynooth University (2015). She completed her viva successfully in June of this year. We at the Irish Women’s Writing Network are thus very pleased to be the first to interview and introduce Dr Tara Giddens to wider attention.

This is the third interview in the emerging voices series which aims to showcase and promote the work of current doctoral students and/or early career researchers who are working in the field of Irish women’s writing in the period between 1880 and 1920.

Dr Tara Giddens

Q: Where did your interest in Ireland more generally, and Irish writers specifically, originate?

TG: I always had an interest in all things connected to Ireland and Scotland but am especially drawn to the folk stories and histories of these places. During my undergraduate degree, I wanted to study Irish literature but my college only offered one Irish lit class and it always filled up so quickly I never had a chance to enrol. Instead, I took Dr Kristin Mahoney’s class on Decadence and the fin de siècle. She introduced me to Oscar Wilde’s Salome (and Aubrey Beardsley’s associated artwork) as well as the New Woman. I fell in love with the movements and figures from the era and decided to pursue a Master’s programme at Maynooth that offered me a chance to immerse myself in the study of Ireland and nineteenth-century literature.

Over the course of the programme, I read a diverse selection of Irish literature from James Joyce and Edna O’Brien to Emma Donoghue and Colm Tóibín. I was also introduced to the Irish New Woman and Dr Tina O’Toole’s book on the subject, which resulted in my MA dissertation on Emily Lawless and Sarah Grand and on-going research interests in Irish New Woman writers. Women like Lawless, Grand, Katherine Cecil Thurston and George Egerton created thought-provoking work that dealt confidently with political and transnational issues at a time when they were expected to remain passive ‘angels in the house’. Their bold and outspoken texts intrigued me.

Q: Your thesis compares the Irish New Woman journalist to her fictional counterparts, with a focus on the period between the 1880s and 1920s. How did you arrive at that research project and what drew you to this time period?

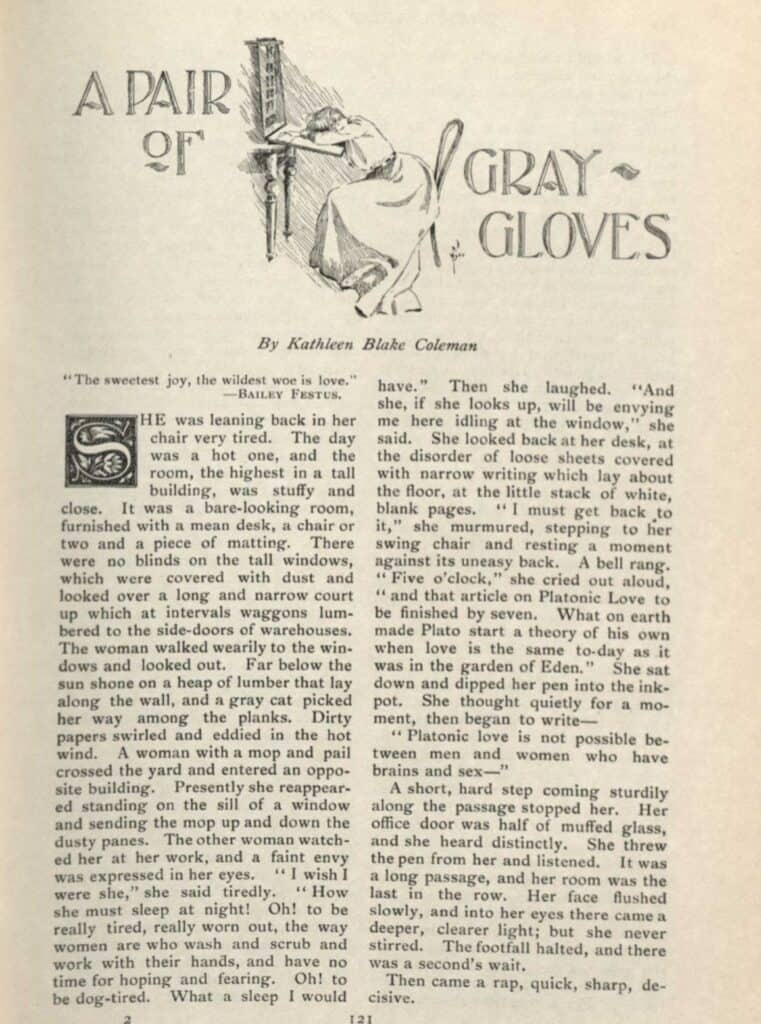

TG: Knowing her work on the Irish New Woman, I met with Tina to discuss potential thesis projects. Recognising that my own experiences in journalism and travel connected to events in Kathleen Coleman’s life, Tina proposed that I research her. This was the starting point for my project, which evolved over time. After further research, I found Coleman’s short story ‘A Pair of Gray Gloves’ (1903), which concerns a woman journalist. From there, my project began taking a more specific shape as an investigation into how Irish women journalists addressed topics like women’s rights, representations of the Irish and gender roles in both their journalism and their fiction.

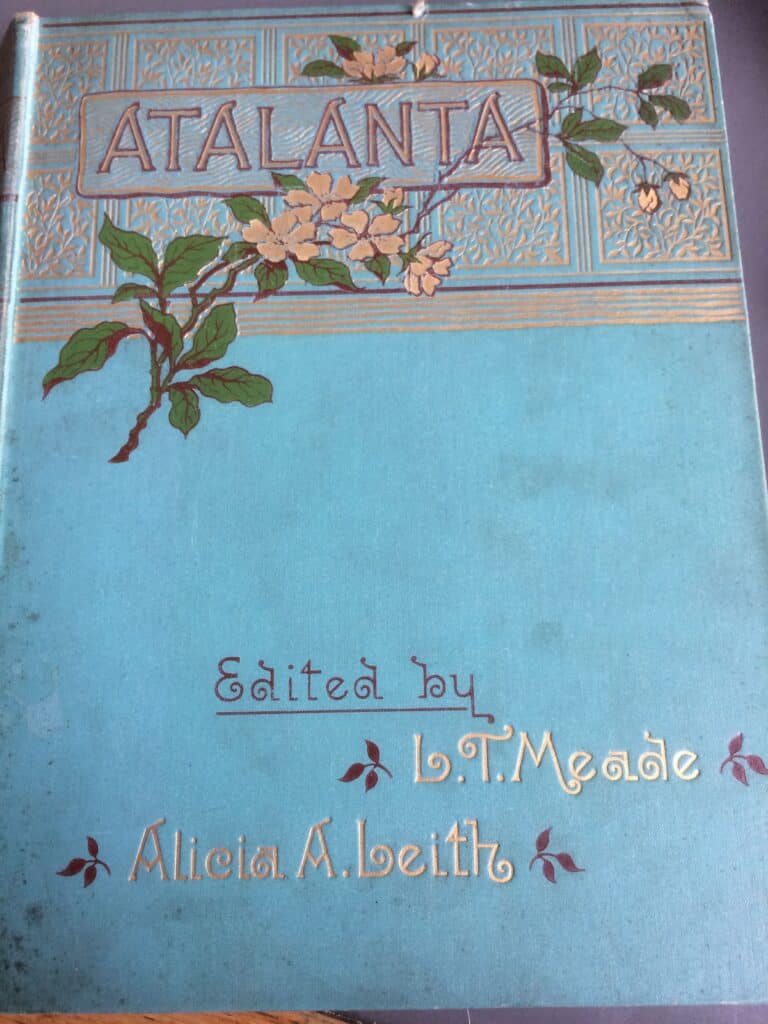

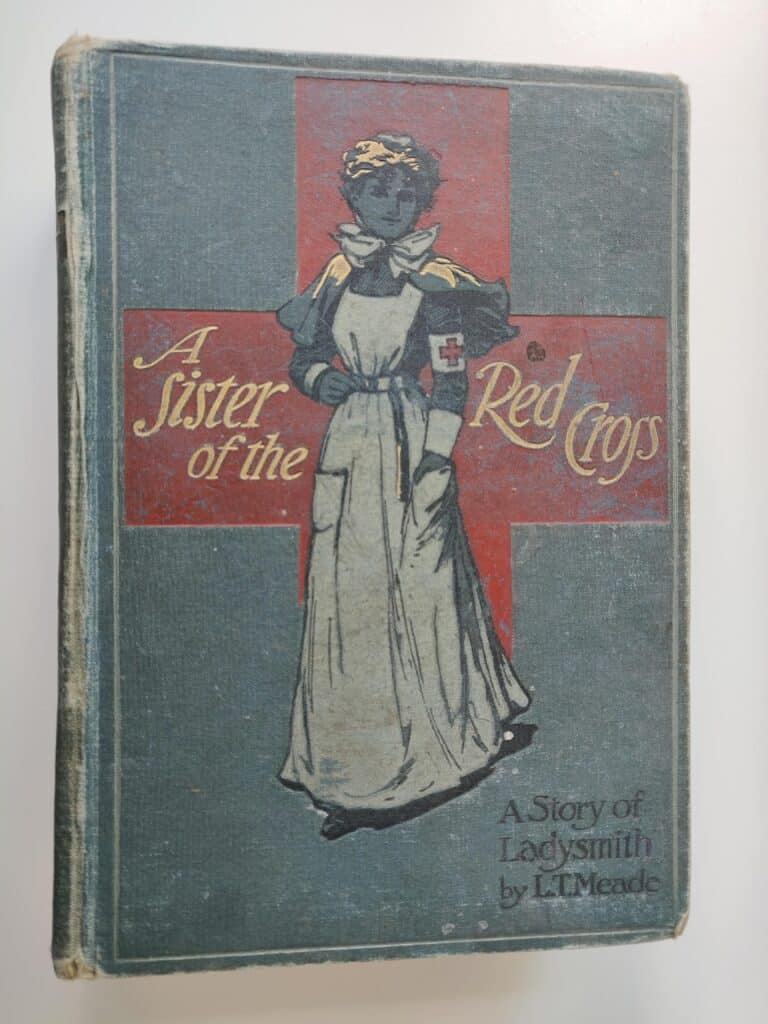

L. T. Meade was the next obvious choice: she was editor of the magazine Atalanta from 1887 to 1893 and also a prolific writer with over two hundred and fifty novels to her name. As she created a very specific (maternal) public persona for herself, there were recognisable correlations between her and Coleman, and I also realised that Meade’s novel A Sister of the Red Cross (1901) had similarities to Coleman’s fiction in that it included a representation of a woman journalist and placed women in what were then unconventional spaces.

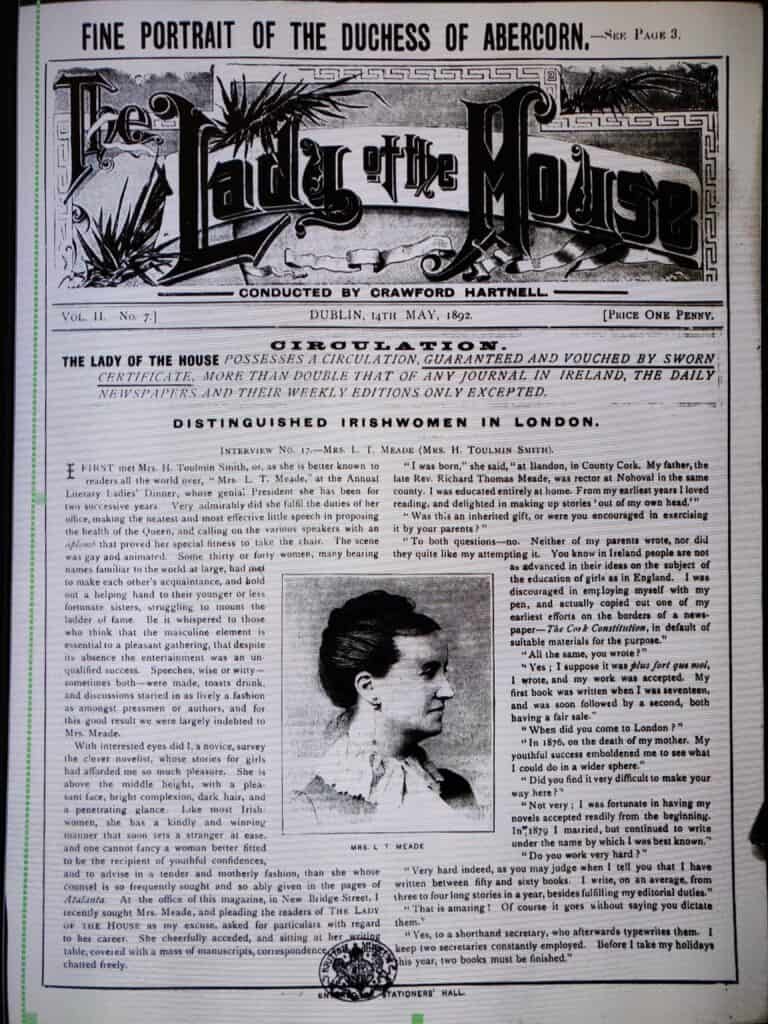

I later came across the work of Charlotte O’Conor Eccles in the Irish magazine The Lady of the House, including her column ‘Distinguished Irishwomen in London’ (1890-1893). In this column, Eccles interviewed professional Irish women including Meade, Alice Stopford Green and Catherine Drew. Both the magazine and Eccles’ journalism are incredibly valuable as they created a space for and preserved Irish women’s voices: one of the few extant places in which these voices can still be accessed. Eccles fit in well with Meade and Coleman as she, too, defended education and careers for women and dealt with her own experiences as a journalist in both her reporting and her novel The Matrimonial Lottery (1906).

Q: You’ve mentioned that you had a career as a journalist prior to pursuing your postgraduate study in Ireland. How does your own journalistic background inform your research?

TG: On a technical level, I started my research with a thorough understanding of how newspapers were run, how relationships within the press room tend to operate, and of the terminology around papers. This gave me something of an insider’s perspective on which to build my research into the periodical press milieu in which these women worked. This knowledge also helped me to understand how the spaces in newspapers and magazines – from the placement of articles, advertisements, and images to the size of headings or a change in the masthead – can be used and altered to influence and direct readers, and I recognised the importance of researching historical publications as whole entities.

It was important to me to acknowledge the trailblazing women journalists who came before me. Many of these women were passionately dedicated to their careers and worked hard to break down barriers. In an interview with Eccles in The Lady of the House, for instance, Irish journalist Charlotte Eliza Humphry acknowledged the significance of her role and told Eccles, “you must remember that we are more or less pioneers and that the difficulties we have had and still have to endure will be considerably lessened for those who come after us” (‘Distinguished Irishwomen in London’, 15 Apr. 1891, 2). As a journalist, I saw the common ground that these women and I had trod when they described working late nights to hit deadlines (that often took a toll on their mental and physical health), how they struggled to find their voice in a male-dominated career and, of course, in their fight to produce work they were passionate about. By highlighting the growth of journalism as a career for women and the hardships they experienced through it – such as struggles over equal pay and putting themselves in dangerous situations to find work – I also recognised the ways in which the profession (and women’s place within it) both has and unfortunately has not changed over time.

Q: In a blog post on the Irish-Canadian journalist and writer Kathleen Blake Coleman, you’ve already told us a bit about the difficulties of piecing together the professional lives of women journalists and the complexities of historical realities, the journalistic voice and fictional representation. We’d love to hear more about your methodological approach. Can you give us a bit of a flavour of your other case studies?

TG: Absolutely! Finding texts that represent women journalists was more difficult than I originally anticipated. Even though more women were entering the career in the nineteenth century, the figure of the woman journalist only very gradually crept into fiction. Despite the impressive amount of fiction that each woman (especially Meade) wrote, the theme of journalism and women journalists rarely appears in their work. Piecing together these women’s stories and their fictional and journalistic output therefore proved a challenge.

Kathleen Coleman

I spent hours looking at microfilm replications of Irish periodicals at the National Library of Ireland to track down their work. A lot of focus and fortitude (and eye drops) were needed when scrolling through the numerous titles and editions available. It always felt worth the time and effort, especially when I came across a wonderful nugget like a rare image of Charlotte O’Conor Eccles. Researching Eccles was like uncovering a hidden gem. She is best known for her article ‘The Experience of a Woman Journalist’ (1893) in Blackwood’s Magazine, yet very little is written about her other works of journalism and fiction.

My research on Eccles so far focuses primarily on her contributions to The Lady of the House and her novel The Matrimonial Lottery, but I was also keen to discuss her portrayals of journalism, nineteenth-century gender roles and the Irish. Covid has slowed my research progress but I am anxious to get back into the libraries and uncover more information on Eccles’ life and her writing. In the meantime, I have created a more detailed timeline of her career and works, including previously unknown articles and translations.

Researching Meade presented its own unique challenges. For instance, while she is the most well-known of the three women journalists I explored, very little information about her personal life is available. My research thus focuses on her editorship of Atalanta and I was able to access the magazine in various ways (online, in libraries, and by buying a DVD of PDFs). My investigations consider the tone Meade created as an editor and analyse the various material, genres and authors included in the magazine to argue that she used it to create a space for girls and women to debate important topics of their time. I compare the messages she promoted in Atalanta with her novel A Sister of the Red Cross: A Tale of the South African War (1901) and discuss how she used these works to create a positive representation of the New Woman (and New Woman journalist) and promote women in the workforce.

Q: No doubt your archival research brings to light many important new discoveries. But what are the challenges of the archive? Are there any questions that you have been struggling to find answers to?

TG: One of the biggest archival hurdles is gaining access to the newspapers and magazines that these women wrote or worked for, especially if those papers were not viewed as important enough to keep (or to digitise), or were edited in online databases in a way that means that the full publication is no longer available. Researchers including Jennifer Phegley have drawn attention to the importance of looking at the full context of a magazine or newspaper, and it is frustrating when someone has edited out parts of a periodical they deemed to be unimportant (i.e. the advertisements and responses from readers), when in fact there is so much insight we can gather from these aspects of the publication.

Another struggle was tracking the women’s biographical information because they either destroyed their diaries and personal letters themselves, or these artefacts were lost or discarded by others. This leaves many questions unanswered as detailed records of their personal circumstances have proved elusive. Additionally, missing census reports have also hindered my research. For example, I was able to find Kathleen Coleman’s baptism report in Ireland and even a marriage license for her parents, but could locate little to no information about Coleman herself after she was married. My curiosity concerning what had happened to her family, however, eventually led me to finding a 1901 census report that listed not only her sister, her sister’s family and Coleman’s mother but also, and most excitingly, Coleman’s daughter, Mary Margaret (or May May), who was said to have died as a baby. I was eager to know more about what eventually happened to May May, but by the 1911 census she had disappeared, and no further information was available. I would love to find out more about Coleman’s family in Ireland and am optimistic that there is information still out there to discover.

These kinds of challenges occur most often: you get a little bit of information and start to unravel it, only to hit a wall or lose the trail altogether. It is a part of archival research that can’t be avoided and, despite the challenges, I really love the research process.

Q: Your work is grounded in a comparative approach that brings into dialogue the historical reality of Irish women’s careers in journalism at home and abroad and their fictional representations. Based on your research to date, how would you characterise the ‘Irish New Woman journalist’? And how does she compare to her fictional counterparts?

TG: My research demonstrates that the Irish New Woman journalist was adaptable, flexible and cunning. Whether it was for financial reasons or from her own interest, she entered a career traditionally viewed as ‘masculine’ and learned how to adjust to what was needed of her. Yet, she also tended to use her position to include issues of personal interest to her by inserting them into her column, through the people she chose to interview, or, as an editor, by including works and articles that dealt with or advocated these initiatives. These could include political issues ranging from women’s rights matters like better education for females and support for women entering the workforce, to the representation of the Irish in the popular press. Despite this, some New Woman journalists would publicly distance themselves from liberal topics and the term ‘New Woman’ while still enjoying the benefits of this role (such as being financially independent, having a career and moving freely in the public sphere).

There are also a lot of similarities between the Irish New Woman journalist and her fictional counterpart. As my own work shows, Coleman, Meade, Eccles and even George Egerton portrayed what can accurately be termed the true-to-life experiences of women journalists in their respective eras. In their work, as in life, being a journalist allowed women to move into spaces they might not have had access to otherwise. In Meade’s novel A Sister of the Red Cross, for instance, a woman becomes a war reporter specifically for the benefit of traveling to Ladysmith: a freedom which Meade acknowledges is only achievable because of her career.

Q: Along with a growing number of other researchers into Irish literature, you are an international scholar (from the USA). What challenges and/or unique insights has this outsider’s perspective on Irish writing presented to you?

TG: The biggest challenge has been trying to learn the intricacies of Irish history and politics and how they impacted and influenced the women I research. I don’t speak Irish and there are cultural references that are unfamiliar to me, so I had to seek some help along the way. While my high school Spanish teacher can tell you that learning languages is not my strong suit, I would love to learn Irish so I can translate things myself in the future!

Being an outsider meant, however, that I started my project with a neutral view of Ireland’s political and cultural history. In some ways, not having preconceived opinions meant I was always open to seeing things from an outsider’s perspective, which has its benefits. Being a newcomer to many topics, I found myself asking a lot of questions. While this sometimes led me down deep research rabbit holes, it certainly strengthened my understanding of the period and resulted in uncovering information that I might not have noticed if I hadn’t been on such a steep learning curve.

Most importantly, I empathised with these women not just because we have shared a career but because, like them, I am an immigrant to a new country, learning new social and cultural rules. Coleman, Meade, and Eccles were inspirational: they overcame significant obstacles in order to become successful writers and financially support themselves and their families, not only in countries foreign to them, but also in an era when women were discouraged from working outside the home. Sharing their stories and analysing their work in new ways has been both rewarding and inspiring.

Tara Giddens Presenting at RSVP conference in Vancouver Canada