The Dreamwork of a Nation: From Virginia Woolf to Elizabeth Bowen to Mary Lavin

Patricia Laurence

For a more detailed reading of this subject matter, see Laurence’s chapter ‘The Dreamwork of a Nation: From Virginia Woolf to Elizabeth Bowen to Mary Lavin’ in ‘The Edinburgh Companion to Virginia Woolf and Contemporary Global Literature (2021), Edited by Jeanne Dubino, Paulina Pająk, Catherine W. Hollis, Celiese Lypka, Vara Neverow.

Too often women writers are viewed by critics and scholars as single subjects immersed in the culture and politics of a nation or their times. If we explore a comparative methodology of ‘shared affinities’ and consider and interpret them in national or international networks and pairings (as the IWWN September forum encouraged) we bring new aspects of their lives and new readings into view. Discovering shared affinities sometimes relieves authors of overworked cultural, political and critical positions in which they are stuck in their own contexts and cultures. Engaged in their own writing and experiments in different circles, classes, times or different parts of the globe, they may be unaware of each other. Nevertheless, placing them side by side on a broader global canvas will illuminate cultural and aesthetic refractions. Abandoning the overworked literary category of ‘influence’, I would argue, usefully repositions British and Irish women writers of different generations on a broader canvas.

Virginia Woolf provides important literary arguments that transform our reading of women’s writing during times of rising nationalism, political conflict and war. She provides a model for women writers living in such periods, creating a new ground for fiction under the blare of nationalist or wartime rhetoric. She encourages women in different countries to write about what is commonly thought a ‘small’ rather than a ‘large’ subject, and to expand the thinking between the private and the public, domestic and public ‘tyranny’ in her writings ‘Modern Fiction,’ Three Guineas and ‘Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid.’

The writers Elizabeth Bowen and Mary Lavin, Anglo-Irish and Irish-American respectively, were inspired by Woolf to register in their writing the ‘small’ shocks, subjects and events in the lives of individuals, families, communities and institutions during times of national conflict. Woolf, born in 1882, was establishing herself as a literary critic when these two Irish writers of a younger generation (Bowen was born in 1899; Lavin in 1912) were beginning to write fiction. Yet they too challenge the claims of critics who assert that women writers engage in ‘small’ or ‘subjective’ events, failing to link their fiction to the wider society, the nation and the world. For example, Bowen provides ‘in-between’ glimpses of war and fragments of remembered selves in her wartime stories collected in Ivy Gripped the Steps (1946) while Lavin creates close-ups of ‘small’ scenes—sometimes through a microscope — of beleaguered widows, loyal wives, enfeebled husbands, independent daughters, and needy clergy in her Irish short stories. Both authors write the kind of fiction projected by Woolf where ‘the accent falls differently; the emphasis is on something hitherto ignored,’ something seemingly ‘small,’ and this, at once, requires ‘a different outline of form’ in the writing.[1] The intimate lives revealed in their stories are not ‘outside’ of politics and history and the world but are a part of the historical texture of life. They present a resistance to dominant views and offer richer interpretations of the future of community: the dream work of a nation.

In addition, Woolf, Bowen and Lavin’s lives touched one another. Letters reveal that Woolf became a treasured friend of Elizabeth Bowen, and they shared literary discussions and joyful meetings at both Bowen’s Court and Monk’s House from the 1930s until Woolf’s death—even though Bowen was not drawn in general to Bloomsbury smugness and claustrophobia. Mary Lavin was a graduate student writing a PhD dissertation about Woolf at University College Dublin in 1938 when Woolf was hardly a popular subject for study. During this time, Lavin had a change of heart and abandoned the dissertation to write fiction. Brenda McKeon reports: ‘I went home,’ said Lavin, ‘and took my thesis and I tore it, I turned it upside down’, and Lavin quite literally wrote her first short story, ‘Miss Holland’ on the reverse page of the thesis and published it in Dublin Magazine in 1939.[2]

Living in England during the blitz, Woolf and Bowen heard warplanes and buzzing bombs overhead, witnessed daily scenes of the destruction and dislocation of people on the streets of London, and, eventually, the bombing of their own homes before and during the Second World War. Lavin lived through the violent aftermath of the Irish War of Independence in 1919-21 and Ireland’s neutrality in the Second World War, as well as the period of the Troubles beginning in the 1960s and lasting into the 90s. Their personal art – written amidst national and international conflict and calls for ‘nationalist’ writing – reveals the struggle of women writers to rescue and preserve their own experiences, feelings, subjectivity, and perspectives on the nations in which they live. These writers do not ignore the wider society or the nation as is often claimed but bring to its attention the cost of nationalism, and the impact of war, patriarchy, gender inequities, class discrimination, church paternalism, colonialism, and capitalism on private lives. Their writing, is, nevertheless, devalued as personal or trivial and subsumed under the rubric ‘domestic’ or ‘home front’ fiction by some mainstream critics, a judgment that limits their scope and impact. For example, writer and critic Colm Tóibín — though acknowledging that Mary Lavin’s writing takes in ‘the history of Irish loss, the idea of a public trauma in Ireland’ — yields to a traditional critical line about her stories:

She was more interested in a character she had invented in all its strangeness and individuality than she was in the wider society; she was more interested in families than politics; she was more interested in the drama around the solitary figure than the drama around Irish history or large questions of identity.[3]

The reading model I’m proposing is one that urges readers and critics to acknowledge that this literary dialogue takes place in a field of power and that the narrative and judgments have largely been shaped by male critics. It is left to readers like ourselves to reject the outdated monotone of such critics, listen to the chords and observe the complexities that are struck in women’s writings. The intimate lives and communities in these stories and novels are not ‘outside’ of politics and history and the world, as critics often claim, but are a part of the historical texture of life. These women writers present a resistance to dominant views and richer definitions of the future of community: the dream work of a nation.

[1] Woolf, V., ‘Modern Fiction’, in The Common Reader, 1st series, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1957, p. 157.

[2] McKeon, B., ‘An arrow in flight: The pleasures of Mary Lavin’, Paris Review, 12 June 2012.

[3] D’Hoker, E. (ed.), Mary Lavin, Kildare, Ireland: Irish Academic Press, 2013. pp. 1 & 23.

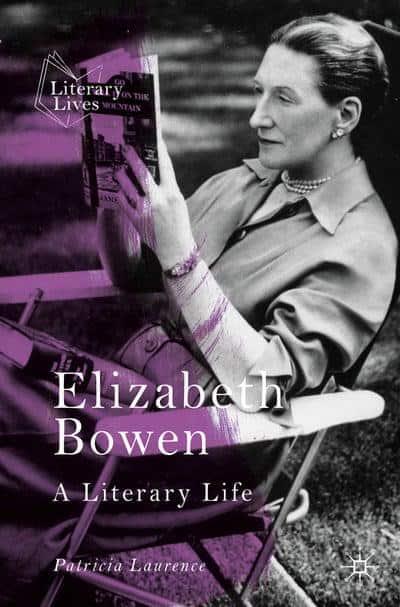

Patricia Laurence has recently published, Elizabeth Bowen, A Literary Life, 2nd ed. 2021.

Patricia Laurence has published widely on transnational modernism, Bloomsbury, and women writers of different countries. Her publications include The Reading of Silence: Virginia Woolf in the English Tradition (1991); Lily Briscoe’s Chinese Eyes: Bloomsbury, Modernism and China (2001); Julian Bell: The Violent Pacifist (2005); and a recent biography, Elizabeth Bowen, A Literary Life (2021, 2nd ed). “The Dream Work of a Nation” (above) appeared in The Edinburgh Companion to Virginia Woolf and Contemporary Global Literature, 2021.

Twitter: @patlaurence423

www.patricialaurence.com

Would you like to submit a blogpost? Check out our guidelines here or email Dr Deirdre Flynn.