With Hannah Lynch and the Ursulines in Tinos- A Story of Remarkable Women

Iliana Theodoropoulou

‘I enjoy perfect freedom’. [1]

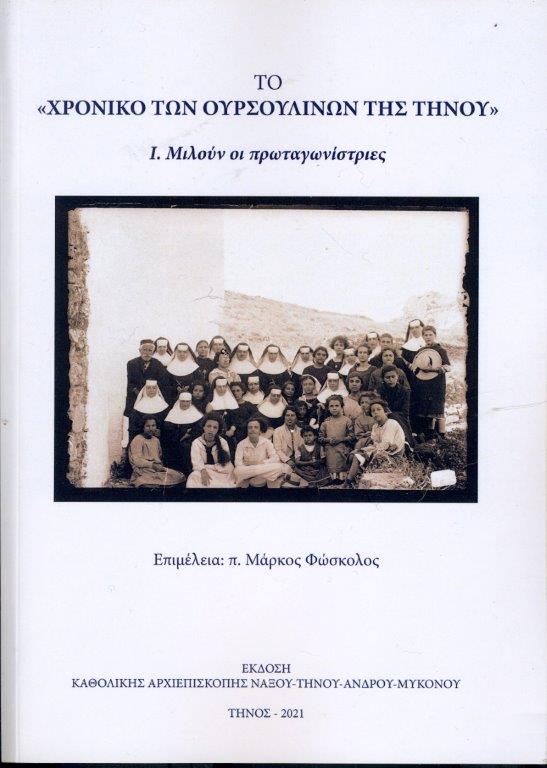

In 1885 Irish writer Hannah Lynch (1859-1904) set out on travels through Greece that would continue over a period of two years. She began this journey by spending more than half a year as a guest at the Ursuline convent in Loutra on the island of Tinos. More than 130 years later – on Thursday evening, August 26, 2021 – Hannah was again a ‘guest’, metaphorically, in the garden of the Ursuline convent where a photograph of her was projected onto the façade. From her viewpoint there, we might say, she once again enjoyed the spirit and the hospitality of the Tinos Ursulines and shared in the celebration of a publication which included a translation into Greek of her essay ‘The Ursulines of Tenos’ (1886).[2] This essay, published in Tinos last summer in The Chronicle of the Ursulines of Tinos,edited by Father Marco Foscolo, is a very valuable testimony of the history of the convent written by this intrepid nineteenth-century Irish writer and traveler.[3]

I discovered Hannah Lynch in July 2020, while I was researching the magnificent history of the order of St Ursula in Greece. I was beginning a visual art project searching the internet when her essay on the Ursulines of Tinos insisted on appearing on my screen. As I was downloading it, just to have a look, I could not have imagined that another project, another path, was just beginning, and that these two projects would eventually merge into one a year later. Lynch’s essay, which had first been published in the Irish Monthly, was about the Ursulines and the history of their convent on Tinos island. This article created an insistent question: why, while all other nineteenth-century travelers to Greece focused mainly on ancient sites, would she, a young Irish novelist, 26 years old, decide to spend more than eight months of her two-year journey in Greece, far away on an island, cloistered with French nuns, in a mountainous village that endured primitive living conditions? It was a question I felt I needed to answer.

Later, in November, I contacted Father Marco Foscolo, the priest responsible for the Catholic Archive of Tinos, in my efforts to gain access to the Ursuline archive for my project. With him I discussed Lynch’s article and over the course of the conversation Father Foscolo invited me to collaborate on his next book about the story of the convent. I suggested that among my contributions to the book would be a Greek translation of Lynch’s study. From that moment I began researching Lynch in order to write a short presentation about her in the book. As I did, I wondered how and why she had traveled to Tinos and her possible connections to the Ursuline convent. Very quickly I discovered the research Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing had done on Lynch and her life, including their book Hannah Lynch 1859-1904, Irish writer, Cosmopolitan New Woman.[4] It was then that I realised how little information there is about her and especially about her time in Greece.

In February 2021 I contacted Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing for their help, and we decided to walk together in Hannah’s footsteps in Greece. Little did we suspect that we would have to wait until the end of the lockdown in July of 2021 before I could travel to Tinos and visit the archive myself.

Le Monastère des Ursulines du Sacré Coeur in Loutra, Tinos

Tinos, Syros and Naxos are three islands with an important Catholic religious community. The Order of St Ursula in Greece dates from 1670, and their first convent was established on Naxos island in 1739. The convent Hannah Lynch visited was founded by the English Ursuline Mary Anne Leeves (Mère Marie de Saint Ignace) in 1862 in the mountainous Catholic village of Loutra on the island of Tinos.

The order’s existence on this island can be traced to the late seventeenth century in its other form, the ‘house Ursulines’ or Angelines. These were nuns who remained in their own village and lived in their own homes, but who also had taken vows, wore the habit, and met once a month in Loutra for spiritual exercises under the guidance of the Jesuits.

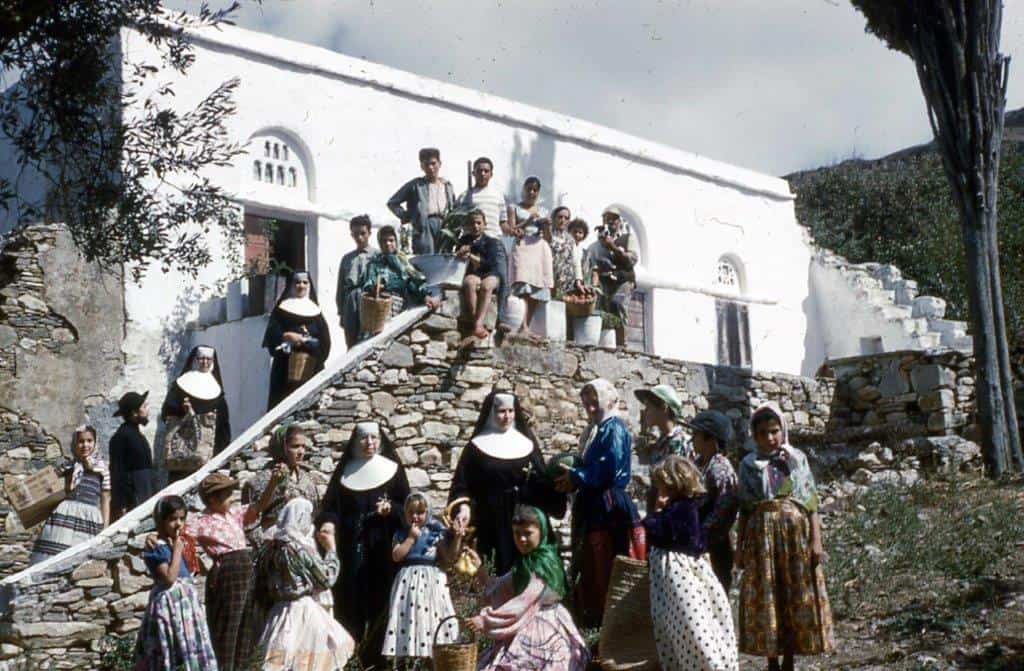

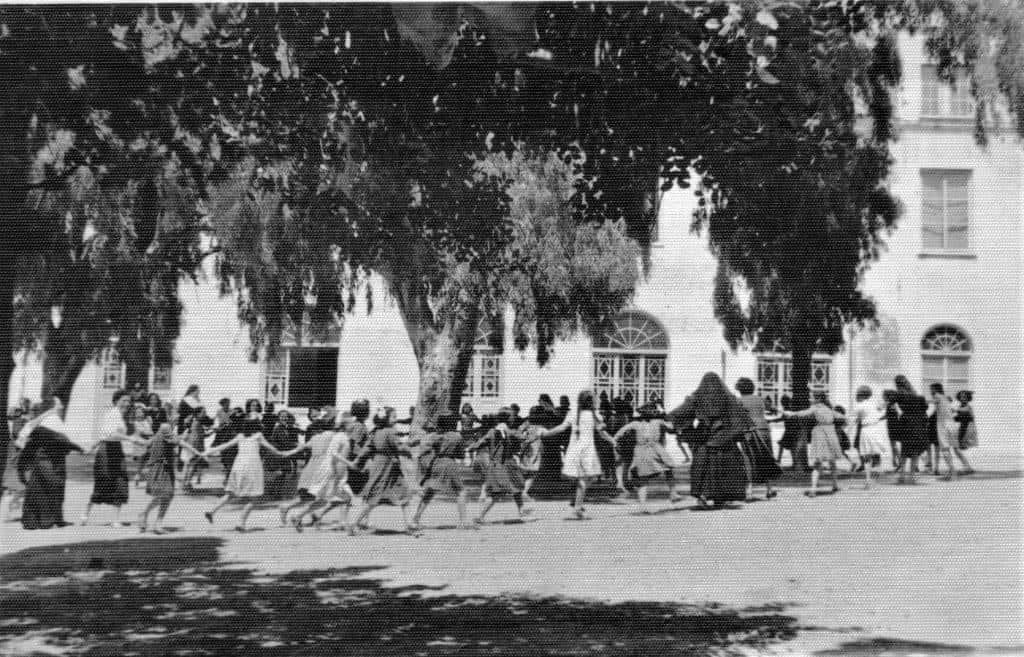

Mary Anne was the daughter of the English Anglican priest Henry Daniel Leeves, a representative of the British and Foreign Bible Society and first chaplain of the British Embassy in Athens. She was born in Constantinople and grew up in a scholarly and spiritual environment with her four siblings. Years after the death of their father, she and her sister Sophie converted to Catholicism in Malta, and both became nuns in Syros island in Greece. Mary Anne took the habit of the house Ursulines of Syros. Years later she went to France, to the Ursuline convent in Montigny-sur-Vingeanne, to complete her novitiate as a cloistered nun before returning to Greece with three French Ursulines in order to found a new convent in Tinos. Their mission was to offer education to the poor girls of the island. In 1885, when Hannah Lynch arrived, they were providing schooling for 48 girls. Boarders at this French convent school came from rich Catholic and Orthodox families from Athens, Smyrna, Constantinople, and Cairo. After the Second World War the high school moved to Athens, and Loutra continued only as a primary school while also providing technical education in carpet weaving.

Archive of the Catholic Archdiocese of Tinos

Hannah in Tinos

Hannah Lynch’s first journey to Greece in 1885 lasted two years. It started in Tinos, where she was a guest of the Ursulines in Loutra. Her stay at the convent is documented in her novels, essays, and personal letters. There are also a few traces of her presence in Tinos in its Archive of the Catholic Archdiocese. It is as yet unknown why she decided to undertake this long trip. A few years later, towards the end of March 1902, she returned to Athens for about six weeks.

In her writings about Greece, she describes her impressions of the country and of Tinos, but focuses primarily on Athens. Her sojourn at the convent is mainly recorded in her two essays published in the Irish Monthly – ‘The Ursulines of Tenos’ and its twin essay ‘November in a Greek island’ – and in her personal correspondence with Father Thomas Dawson.

On the 3rd of October 1885 Hannah Lynch wrote her first letter to Father Dawson from Tinos.[6] In it, she discusses her adventurous departure from Liverpool, her journey on the ‘SS Roumelia’, her first impressions of Tinos, her own room with a writing table and the warm hospitality of the nuns.

This letter was followed by two more, in December 1885 and in February 1886. In her final letter she describes both the convent and her daily life. She tells Father Dawson that she is learning Greek and has a few teaching assignments, but mainly she writes about being very happy, pampered and loved by all the nuns and the Superioress Mary Anne Leeves.

Archive of the Catholic Archdiocese of Tinos

‘The Ursulines of Tenos’

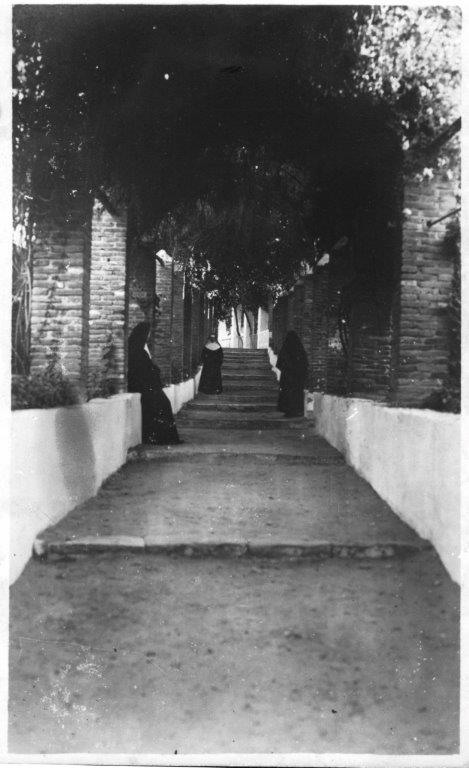

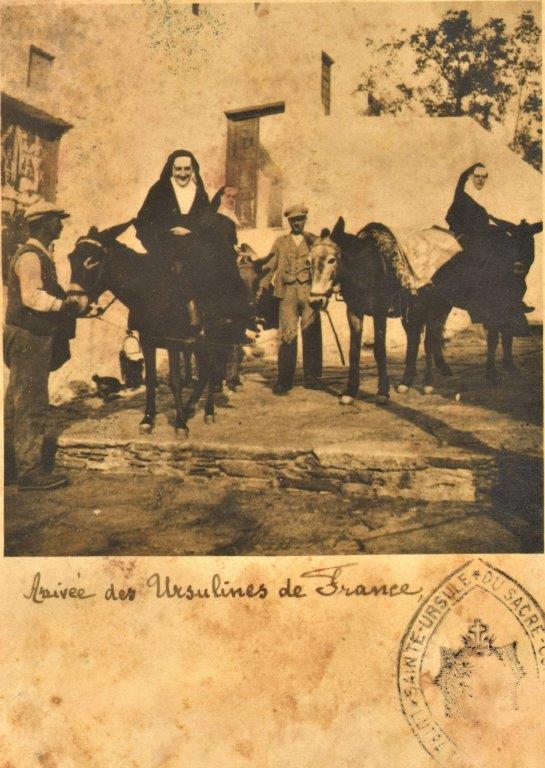

Her essay, ‘The Ursulines of Tenos’, is, as suggested by its title, primarily about the convent in Loutra. In the first part of the article, she traces the history of its foundation, the enormous difficulties and deprivations that the nuns had to endure – their courage, persistence and sacrifices. She begins by directly writing about the four nuns from the Ursulines of Montigny sur Vingeanne – Mary Anne Leeves and three French Ursulines – who first traveled to Tinos. Loutra was not easy to reach. One had to travel to Hermoupolis, the main town of the Cyclades, in Syros island, and from there cross to Tinos by a smaller boat. From Tinos town to Loutra was an exhausting ride on mule or donkey, on narrow, dangerous and sheer paths. As the journalist Baron de Mandat-Grancey wrote, this convent should have ideally recruited nuns with previous work experience in a circus![7]

Little had changed by the time that Hannah first visited the island: the only way to travel continued to be on mule or on foot. In 1885 when Hannah was there, the first Superioress had died but three of the original four nuns were still alive. I imagine them sitting with Hannah in the community room in the winter evenings, by the fire, telling their story.

In the second part of her text Hannah describes the convent as it was in 1885: a French institution, in ‘the middle of nowhere’, in a primitive village, without the facilities of the late 19th century. It was without doubt a surprise to discover this French school high up on an island mountain, famous in the entire Eastern Mediterranean, with the latest education methods, pianos and medical care. At the end of her article, Lynch asks the readers of the Irish Monthly to contribute to the convent. There is, however, no trace of any money coming from Ireland in 1886 or 1887 in the registry of the convent in the archive.

Hannah Lynch’s memoir of the convent nuns was not the first to tell their story, nor was it the first to be published. Years earlier, the first Superioress of the convent, Mère François de Sales, had in fact written about its founding in her letters to the bulletin Oeuvres des Écoles d’ Orient. Mary Anne Leeves had likewise written a longer report, ‘Comment cette Maison prit naissance’ (1872), about her life, her conversion, and the foundation of the convent in Loutra, the first very difficult years, the purchase of land, and the construction of the building. This text has been reproduced several times by the sisters and it was most probably available to Hannah Lynch in 1885.[8]

Lynch was also not the only visitor to Loutra in the 1880s. Among the other travelers were Theodore and Mabel Bent, and the Jesuit Victor Baudot. The French journalist, Edmond de Mandat–Grancey, visited Loutra and wrote about the convent in his books. Yet Hannah Lynch’s essay remains unique for two reasons: First, it is not part of a travel book or a paragraph in a chapter about Tinos. Instead, it is an individual article published in an Irish literary magazine. Moreover, it was written on the spot as she was living with the nuns, with whom she was almost certainly discussing her work. It is also unique because Hannah was absolutely not in favour of religious teaching orders (made clear in publications such as her autobiographical novel Autobiography of a Child (1899) and numerous essays) or the propagation of the French language and culture as an imposition on another culture. Yet her essay is objective, clearly praising the nuns for what they were and for their important contribution to the education of girls on Tinos. Why then would she praise these Ursulines?

The first reason must be because she was happy there, as she writes to Father Thomas Dawson.

‘In fact I enjoy perfect freedom’, Hannah Lynch wrote to him in her first October letter. She was indeed content and remained at liberty in Loutra, and this freedom – in movement, in her inspired texts, in the garden, in the mountains, in the scented air, in the sound of the birds, in her descriptions of landscape – is apparent everywhere in her Greek texts.

But secondly, and more importantly, it must have been because the Ursulines were extraordinary women: “feminists ante litteram”,[9] intelligent, determined, strong. As Hannah writes: ‘Yet, nevertheless, this gigantic feat is what the nuns, by a peculiar genius, patient perseverance, and severe economy, have accomplished.’ When I first read these lines, I thought she must have been exaggerating. But then I visited the convent last summer and realised that every word of hers, every observation, could not have been more accurate. The building and the premises, partially in bad condition and with the urgent necessity of restoration, must have been a miracle in the late 19th century.

Loutra was remote, inaccessible, extremely poor and conditions for inhabitants were primitive. But on entering the convent, the visitor would find themselves transported to France, to a completely modern institution, equipped with the most recent educational and medical materials. The new building included a dormitory and music rooms. There were thirty pianos and an organ, all carried either on foot or on mules. This was achieved exclusively by women: those first four adventurers and those who subsequently joined them. The second Superioress, Mère Marie du Précieux Sang Lamidey, was the architect of the new building and later received the first prize of 2500 French francs for her work by the Académie Française in 1900.[10] The convent was also the personal dream of Mary Anne Leeves, another remarkable woman now forgotten; a heroine, as Victor Baudot calls her: ‘Qu’il me suffise de dire qu’une femme héroique, qui se cache sous le nom de Marie de Saint Ignace, a eu le courage de tenter cet effort surhumain , et qu’elle est parvenue , après bien des années de souffrances a réaliser le plus cher de ces voeux’.[11] This gigantic feat, as Hannah describes it in her essay, was dedicated to the education of women. Young poor girls of the island were literally adopted by the nuns, and had a chance to have access to education and a life otherwise unthinkable. It was a space created by women for women, an exclusively feminine space, and no doubt Hannah Lynch approved.

Many thanks to Father Marco Foscolo for the permission to use photographic material from the Archive of the Catholic Archdiocese of Tinos, to Kathryn Laing for her invaluable help, patience and support, and to blog editors Whitney Standlee and Deirdre Flynn for generous assistance preparing the blog.

Iliana Theodoropoulou: I am a visual artist from Athens, Greece. I studied Surveying Engineering in Athens and Photogrammetry in London. I spent several years doing research and working in Berlin. Since my return to Greece, I have been exclusively working as a visual artist. My main field is painting, where my work inhabits the border between abstraction and landscape painting, but I also explore the possibilities of photography and film. I have had three solo exhibitions and participated in several group shows.

[1] Letter from Hannah Lynch to Father Thomas Dawson, cited in Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing, Hannah Lynch Irish writer, cosmopolitan New Woman, Cork: Cork University Press, 2019, p. 16.

[2] Hannah Lynch, ‘The Ursulines of Tenos’, The Irish Monthly, vol. 14, May 1886.

[3] This essay was translated in Greek and along with a short biography, was included The Chronicle of the Ursulines of Tinos, edited by Father Marco Foscolo, and published by the Catholic Archdiocese of Naxos-Tinos-Andros-Mykonos. At the book presentation which took place last August in Loutra, many women who were pupils at the school were present. I had the chance to talk about her to them and read extracts from her article, in the convent garden, at the exact location where it was written.

[4] Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing, Hannah Lynch Irish writer, cosmopolitan New Woman. Cork: Cork University Press, 2019.

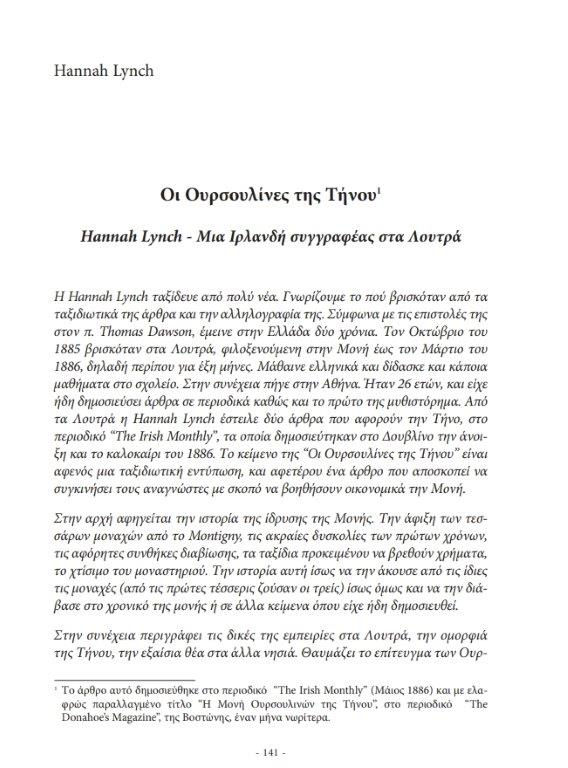

[5] Ιλιάνα Θεοδωροπούλου , “Οι Ουρσουλίνες της Τήνου , Hannah Lynch – Mια Ιρλανδή συγγραφέας στα Λουτρά” [Iliana Theodoropoulou, “The Ursulines of Tenos , Hannah Lynch – An Irish writer in Loutra” ], The Chronicle of the Ursulines of Tinos (in Greek) p.141-151

[6] Correspondence with Father Thomas Dawson, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds. For further details about Thomas Dawson and a discussion of Lynch’s correspondence with him, see Binckes and Laing.

[7] Mandat-Grancey E., Aux pays d’Homère, Librairie Plon: Paris 1902.

[8]The Tinos Ursulines loved telling their story, the story of the extraordinary and adventurous foundation of the convent. So much, did they love it that in 1962, at the celebration of the hundred years they recreated it as tableau vivant and as a theatrical play.

[9] Father Marco Foscolo, ed., The Chronicle of the Ursulines of Tinos, Catholic Archdiocese of Naxos-Tinos-Andros-Mykonos: 2021, p. 10.

[10] Académie Francaise, Séance Publique annuelle, 22.11.1900, Typographie de Firmin -Didot: Paris 1900.

[11] Baudot, V., Les îles de marbre, ou Excursion dans la mer Égée, Société de St Augustin: Paris 1891.