Hope and Hunger in a Stricken Land: Jane Wilde and the Great Hunger

Christine Kinealy, Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University

This is an extract from Professor Christine Kinealy’s article ‘Hope and Hunger in a Stricken Land: the Wilde Family and the Great Hunger’ in Reading Ireland, issue 12, edited by Adrienne Leavy.

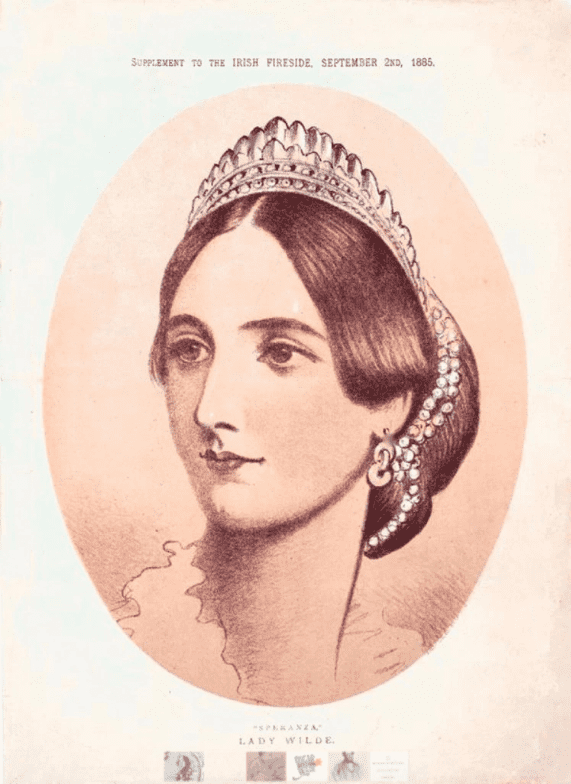

Speranza (Jane Elgee) and William Wilde, affluent members of the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, were both champions of the poor during the Great Hunger. Following their marriage in 1851, they achieved a celebrity status in their native country and an enviable life-style. William, a brilliant eye and ear doctor, was named as Oculist-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria and, in 1864, was knighted for his services to the Empire, particularly for his work on various Irish censuses. Jane and William, who resided in the prestigious Merrion Square, attended many vice regal functions at Dublin Castle, the symbol of British rule in Ireland. Yet this privileged couple, in multiple ways, advocated for the Irish poor and they provided some of the most searing criticisms of the British government’s response to the Famine. Their second son, Oscar, would later use his own skills to challenge British rule in Ireland.

SPERANZA

Jane Elgee was born in Wexford in 1821 to an Anglican, conservative family. Her background, upbringing and gender made her an unlikely candidate to become a writer for the Nation,a champion of the oppressed, or a gifted linguist whose translations would include Lamartine’s History of the French Revolution in 1850.[i] Moreover, throughout her adult life, Jane was a radical nationalist, a political activist and spokesperson for the Irish poor. She reinvented herself as “Speranza,” the Italian word for hope. Recalling his first meeting with her, Charles Gavan Duffy, the editor of the Nation, who had assumed the anonymous writer of such strident poetry was a man, stated: “Miss Elgee was the daughter of an archdeacon of the Establishment, and had probably heard nothing of Irish nationality among her ordinary associates.”[ii] When interviewed in later life, Speranza made a similar observation, saying, “I was quite indifferent to the National movement, and if I thought about it at all I probably had a bad opinion of its leaders; for my family was Protestant and Conservative, and there was no social intercourse between them and the Catholics and Nationalists.”[iii]

The Nation newspaper was the mouthpiece of Young Ireland, a dynamic group of Protestant and Catholic nationalists who were increasingly moving away from Daniel O’Connell’s “Old Ireland.” Speranza sided with the former and the radicalism of the charismatic Thomas Francis Meagher and John Mitchel. An insight into her character, regardless of her youth and gender, was provided by her criticism of O’Connell, and his moderate views, in verse:

He whose broad forehead was circled with might.

Sunk to a time-serving, driveling inanity.[iv]

Speranza’s early contributions to the Nation coincided with the reappearance of the potato blight in Ireland. Inept and inappropriate relief measures introduced by the government in London transformed the food shortages into a deadly famine. Speranza used her penmanship to champion the Irish poor and to highlight their hunger and oppression. These themes were evident in several her poems, including “The Voice of the Poor”:

Before us die our brothers of starvation

Around are cries of famine and despair

Where is hope for us, or comfort, or salvation

Where—oh! Where? [v]

It was also a theme in “Foreshadowings”:

Woe! ‘Tis the black steed of famine that cometh

At the breath of its rider the green earth is blasted,

And childhood’s frail form droops down, pallid and wasted [vi]

Speranza’s most famous poem, however, appeared in the Nation on 23 January 1847. Entitled “The Stricken Land’, but subsequently renamed “The Famine Year,” it was a searing indictment of the relief policies of the British government –the “stranger.”

WEARY men, what reap ye?–Golden corn for the stranger.

What sow ye?–Human corses that wait for the avenger.

Fainting forms, hunger-stricken, what see you in the offing?

Stately ships to bear our food away, amid the stranger’s scoffing …

From the cabins and the ditches, in their charred, uncoffin’d masses,

For the Angel of the Trumpet will know them as he passes.

A ghastly, spectral army, before the great God we’ll stand,

And arraign ye as our murderers, the spoilers of our land.

The poem is remarkable for a number of reasons. It presented a visceral, unsanitized and rare view of the impact of famine on the human body and human spirit.[vii] Speranza depicted the starving as dehumanized and hollow forms who are no longer recognizable as people but are, in her words, “a ghastly spectral army.” In doing so, she provided them with a presence and a voice—both of which remained even after their corporal death. Moreover, in format and content, Speranza was breaking new ground, which represented a “poetic experimentation,” as famine and starvation described so graphically were not traditional topics for English poetry. Unwittingly also, her powerful language and innovative format provided a model for how subsequent famines in Ireland and other parts of the empire would be viewed and described.[viii]

At a time when a new revolutionary zeal was emerging throughout Europe, including Ireland, Speranza’s writings were not only incendiary, but in the context of the repressive legislation introduced by the British government in 1848, treasonous.[ix] The wholesale arrest of leaders of Young Ireland in the spring and summer resulted in two women—Speranza and Margaret Callan—taking over the publication of the Nation. In her most inflammatory writing, “Jacta Alea Est” (The Die is Cast), published on the same day that the ineffectual rising in Ballingarry, County Tipperary, was taking place, Speranza exhorted the men of Ireland to take up arms:

Courage! Need I preach to Irishmen of courage? Is it so hard a thing then to die Alas! do we not all die daily of broken hearts and shattered hopes …No! it cannot be death you fear; for you have braved the plague in the exile ship of the Atlantic, and the plague in the exile’s home beyond it; and famine and ruin, and a slave’s life and a dog’s death ; and hundreds, thousands, a MILLION of you have perished thus. Courage! you will not now belie those old traditions of humanity that tell of this divine God gift within us … Now is the moment to strike, and by striking save, and the day after the victory it will be time enough to count our dead …[x]

The Great Hunger not only killed approximately one million Irish poor, it ended the cultural and political awakening associated with Young Ireland. Although Speranza seemed to disappear from public life after 1848, she did continue to write for the Nation, albeit under different pseudonyms.[xi] Despite marriage in 1851 and subsequent motherhood, Speranza remained in the public eye, with literary “salons” in her Dublin home. Through the weekly gatherings, the Wilde children would meet the leading intellectual writers and political thinkers of the day.The salons continued after she moved to London following William’s death, regardless of her straightened financial circumstances. There, she joined her two sons.[xii]

In later life, Speranza continued to write and publish and be politically engaged. In 1864, a compilation of her poems was published, most of them having appeared in the Nation between 1846 and 1848. A second edition appeared in 1867 and an enlarged version in 1871. The 1864 publication was dedicated to her sons, Willie and Oscar, with the inscription, “I made them indeed/Speak plain the word country.”[xiii] That Speranza remained indelibly linked with the Famine was evident, with her poems often reprinted in the nationalist press. She was also referenced in a review of Rev. O’Rourke’s 1875 publication, The Great Famine, with the first stanza of her now-famous poem quoted to explain to a new generation the tragedy that had occurred 30 years earlier.[xiv] On the other side of the Atlantic, Speranza continued to be remembered for her role in Young Ireland and her poetry of “the Famine and the Exodus.” A review of her poetry in the Boston Pilot in 1879 noted, “Her sympathy for her country’s sufferings in these days is only equaled by her scorn of those whom she blamed for letting such things be. How her indignation blazes forth at the coolness with which the loss of a million of her countrymen is taken.”[xv]

The imprisonment and harsh treatment of the Fenians, a republican movement founded in the wake of the Great Hunger, led Speranza to again take up her poetic pen:

HAS not vengeance been sated at last?

Will the holy and beautiful chimes

Ring out the old wrongs of the past …

Will the eyes of the pale prisoners rest

Once again on their loved mountain scenes [xvi]

Speranza’s continued political involvement led one Irish newspaper to write of her in 1892, “She pleaded in prose and verse for the liberation of the Fenian prisoners in ’67; she sympathized with the Land League movement, and now the Home Rule cause has in her an ardent supporter.”[xvii] Additionally, Speranza wrote on subjects as diverse as women’s suffrage and the role of Irish America in winning independence for Ireland.

In 1881, from her London home, Speranza reconnected with her Irish roots, publishing the delightful “Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland.”[xviii] The book concluded with “Sketches on the Irish Past” that included some of William’s writings. The publication also returned to themes that had informed much of Speranza’s writing and politics: namely, the Famine and emigration. She lamented the continuing mass emigration, a theme which she and William frequently wrote about:

A million of our people emigrated; a million of our people died … The echoes of the old tongue—is dying out at last along the stony plains of Mayo and the wild sea-cliffs of the storm-rent western shore. Scarcely a million and a half are left of people too old to emigrate, amidst roofless cabins and ruined villages, who speak that language now. Exile, confiscation, or death, was the final fate written on the page of history for the much-enduring children of Ireland.[xix]

Speranza died in February 1896, while her beloved son Oscar was languishing in Reading Gaol. Dubbed the “National Poetess of Ireland,” Speranza’s later years were marred by poverty, scandal and personal tragedy.[xx] During her lifetime, she was described as “the world-famed ‘Speranza’, dear to Irish hearts, whose patriotic poems and lyrics are familiar household words wherever the liberty-inspired genie of English literature are used and appreciated.”[xxi] When she died, Oscar had been incarcerated for just over eight months; Speranza had been denied permission to visit him and he was refused permission to attend her funeral. Many newspapers in Britain and Ireland noted her passing. As the Wexford People explained:

Her connections, her faith, her position in society, all seemed to forbid any connection with the popular movement which enveloped Ireland in the forties. But she was first attracted and then swept away by the enthusiasm of the hour … The poems of Speranza have in them no trace of feminine softness. This young girl denounced the enemies of Ireland and lamented her woes in verses stern and majestic as the strain of a Hebrew prophet. The awful disaster of the Famine is reflected in all its horror in her verses.[xxii]

In a lengthy article, the Dublin Evening Herald reproduced in full, “the magnificent article,” Jacta Alea Est. Her funeral, however, was private with, it appears, only her son, William, his wife and one other person in attendance.[xxiii] Oscar paid the funeral expenses but, family impecunity meant Speranza was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in common ground, with no headstone.

Since completing her PhD at Trinity College in Dublin, Christine Kinealy has worked in educational and research institutes in Ireland, England and, more recently, in the U.S. In September 2013, Professor Kinealy was appointed the founding Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut. Professor Kinealy has published extensively on modern Ireland, her books including This Great Calamity. The Great Famine in Ireland (1995 and 2007), Frederick Douglass and Ireland. In his own words (2018) and Black Abolitionists in Ireland (2020). In 2017, she received an Emmy for her contribution to the documentary, ‘The Great Hunger and the Irish Diaspora’.

For more information on Reading Ireland – click here.

Would you like to submit a blogpost? Check out our guidelines here or email Dr Deirdre Flynn.

References

[i] Although beloved and respected during her lifetime, her reputation as a poet and a nationalist (and even as a mother) suffered following Oscar’s fall from grace. Her reputation is being restored, see, Eibhear Walshe, Jane Wilde (Brighton: Edward Everett Root, 2020).

[ii] “From history of Young Ireland by Charles Gavan Duffy,” Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 9 August 1884.

[iii] “Our Irish Portrait Gallery. Lady Wilde,” Irish Society (Dublin), 9 January 1892.

[iv] This poem, “A Lament,” was published in the Nation on 5 December 1847. It was not included in the anthology.

[v] Lady Jane Francesca Agnes Speranza Wilde, Poems by Speranza (Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son, 1864), p. 14.

[vi] Ibid., ‘Foreshadowings,” pp. 18-19.

[vii] The anthology included a translation (by William Wilde) of the 1739, “A Lament for the Potato,” which opened:

There is woe, there is clamour, in our desolated land,

And wailing lamentation from a famine‐stricken band;

And weeping are the multitudes in sorrow and despair, For the green fields of Munster lying desolate and bare …

[viii] Amy Martin, “The Skeleton at the Feast. Lady Wilde’s Famine poetry and Irish international critiques of food scarcity,” in Christine Kinealy, Jason King and Ciarán Reilly, Women and the Great Hunger (Hamden: Quinnipiac and Cork University Press, 2016), pp. 150-8.

[ix] Christine Kinealy, Repeal and Revolution. 1848 in Ireland (Manchester University Press, 2009).

[x] The editorial appeared in the Nation on 29 July 1848. Charles Gavan Duffy was accused of writing it, although Speranza publicly claimed authorship.

[xi] She used the pseudonyms “A,” and “Stella and Vanessa,” see Nation, 30 November 1850.

[xii] After Oxford University, Oscar had relocated to London. Willie Wilde (1852-99) had been called to the Irish bar. In 1879, he and his mother moved to London where he worked as a journalist. He was constantly in debt.

[xiii] Lady Jane Wilde, Poems by Speranza (Dublin: James Duffy, 1864).

[xiv] “The Great Famine” reviewed in the Nation, 5 February 1875.

[xv] The Pilot (Boston), vol. 42, 12 April 1879.

[xvi] “The Prisoners, Christmas 1869,” appeared in the 1871 edition of Poems.

[xvii] Irish Society (Dublin), 31 December 1892.

[xviii] Lady Wilde, Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland. With Sketches of the Irish Past (London: Ward and Downey, 1881), p. 327.

[xix] Ibid., p. 327.