Research Pioneers 11: Julie Anne Stevens

Julie Anne Stevens is the leading expert in Irish literary studies on the works of the cousins Edith Somerville and Martin Ross. With two monographs on these collaborators – The Irish Scene in Somerville and Ross (2007) and Two Irish Girls in Bohemia: The Drawings and Writings of E.OE. Somerville and Martin Ross (2017), she has made an important contribution to the corpus of research on Irish women’s writing by showcasing the rich archival resources available in studying Irish women’s literary history in national and transnational contexts from the Land War to the Belle Époque. Throughout her career, Stevens has published on women writers, including Elizabeth Bowen, Mary Lavin, and Deirdre Madden. Her interests have always been on those writers who were either considered marginal or were believed to have written works in what were once deemed marginal genres, from children’s literature to ghost stories. Firmly grounded in an impressive array of archival material, her research weaves together literature and art, genre and readership.

Stevens lectures in Dublin City University where she served as the Director of the Centre for Children’s Literature and Culture (2009-17) as well as the Research Convenor of the School of English (2016-17).

This is the eleventh interview in the Research Pioneers Series conducted by Anna Pilz & Whitney Standlee. Our first interview with John Wilson Foster is available here, Heather Ingman and Clíona Ó Gallchoir is here, James H Murphy is here, Heidi Hansson is here, Lucy Collins is here, Gerardine Meaney here, Margaret Kelleher here. David Clare, Fiona McDonagh and Justine Nakase here, Elke D’hoker here and Mary S Pierse here.

Q: What initially drew you to the study of Irish women’s writing of this period?

Julie Anne Stevens

JAS: My interest in women’s fiction as a graduate student in 1980s University College Galway led to a study of Mary Lavin and the Irish short story. I recall meeting Lorna Reynolds in the university, but my sense of feminist camaraderie did not come so much from the faculty as from my fellow graduate students: the poets Mary Coll (working on Kate O’Brien) and Mary O’Malley Madec (Irish itinerant Cant), Barbara Geraghty (Padraic Colum), Caitriona Clear (nuns in nineteenth-century Ireland), Anne Byrne (female poverty in Ireland). Friendship with this group of women developed my strong interest in what is considered marginal material.

At that time Lavin was still publishing, and she agreed to meet me to talk about women’s writing. She was especially anxious that her legacy would endure; conversations included her asking me about possible contacts with American publishers. For the first time I realised how fragile the writer’s position might be. Books could disappear like ghosts. She was asking me about American publishers because I was leaving for the United States halfway through my studies.

Geographical distance sharpened my interest in Irish writing and I sought out Irish studies in Minnesota and California, taking classes offered by Joyce scholars such as Chester Anderson and Declan Kiberd (who was visiting the University of Minnesota), or Patrick Ledden in University College San Diego. Throughout this time, I frequently came across Somerville and Ross who wrote and illustrated hilarious short stories. I thought them funnier than Joyce, with a sharp humour reminding me of the Galway crew I had left behind and perhaps even more of my Dublin mother, Nuala Walsh. When I returned to Ireland in the 1990s and started research in Irish writing in Trinity, I became deeply engaged in Somerville and Ross’s work because of its scope and richness: the European, British and American connections, the visual component, the comic parodies in their artful short stories and novels, and the intriguing fact of collaboration by two prominent suffragists.

Q: Which researchers helped and influenced your own work?

JAS: My father Chris Stevens lectured in UCG, and he encouraged my interest in the visual arts and short fiction. He brought me to lectures on Kokoschka and Turner in the National Gallery of Ireland and gave me Stephen Crane’s stories to read. I think that his American Presbyterian background gave me confidence in my own ability to read and interpret books.

However, my interest in women writers mainly found support when I started working with scholars like Riana O’Dwyer in UCG and then Antoinette Quinn and Nicholas Grene in Trinity. When in TCD, I worked with a series of prominent academics in the field: Terence Brown, Robert Tracey, Terry Eagleton. And I recall being very struck by certain works, like Catherine Nash’s work on gender and landscape in the early 1990s, Joep Leerssen’s Remembrance and Imagination (1996), Angela Bourke’s The Burning of Bridget Cleary (1999). I joined the Society for the Study of Nineteenth Century Ireland where James Murphy and Margaret Kelleher had a significant impact on the kinds of discussion taking place about Irish writing. However, throughout this time my main influences were academic friends who crossed disciplines: the mathematician and Joyce scholar Patrick Ledden; my good friend, the archaeologist and historian Elizabeth Fitzpatrick of UCG with whom I have hiked many Irish landscapes; neuroscientist and co-teacher on Irish literature and the visual, Christopher Comer of the University of Montana. Their intellectual curiosity and ability to share ideas across different areas gave me the resolve to develop my own methods of writing and research.

My interest in the visual arts has been a constant of my life, and I have been fortunate to work/collaborate with art historians Anne Crookshank, Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch, and Bruce Arnold. Bruce Arnold’s writing about Jack Yeats and Mainie Jellett influenced especially my approach to Irish artists. Most recently I have been stimulated by the work of fellow scholars in my area, such as Heidi Hansson on women’s periodical writing and Kathy Laing on literary networks.

Q: You are the leading scholar on the works of Edith Somerville and Martin Ross. In both your monographs The Irish Scene in Somerville and Ross and Two Irish Girls in Bohemia, you are particularly interested in literary collaboration and the relationship between text and image. In the former, you delve into writing and book illustration while in the latter you focus on Somerville’s engagement with art via her sketchbooks. How has this work informed your broader thinking about women, art, and networks in national and transnational contexts?

JAS: I am increasingly aware of how much the women of this period shared ideas, how they may have moved from the visual arts to writing, and how their different networks overlapped. Although a writer or artist tended to move in one particular network, this did not necessarily stop her from dropping in and out of other groups. These networks could reach across the globe, and increasingly I am aware of the importance of the web of connections established. I think that working in Irish women’s writing of this period makes one much more aware of the need to move across nations and disciplines rather than restricting study to particular locations or groups. At the same time, I am interested in exploring how ideas circulating in the great centres of art and literature become incorporated within the conversations developing in more local settings. Discussion in the Paris cafés had to be adapted to suit the exigencies of life in Galway or Liverpool. Some of my work has included the study of the clusters of artists and writers who worked in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century, and their interaction had lasting consequences in all sorts of places. Also, it seems to me that as a result of the collaboration and networking of the period, researchers need to be open to reaching across nations to understand better these connections and their significance. For instance, Somerville’s sketches include one of the Finnish artist/writer Helena Westermarck while both were working in the Académie Colarossi in Paris. A brief conversation with Heidi Hansson of Umeå University swiftly alerted me to the possible significance of this connection which I subsequentially pursued thanks to Professor Hansson. Clearly, crossing nations as well as crossing disciplines can lead to fruitful scholarship.

Q: Can you recall a particular ‘Eureka moment’ from the archives?

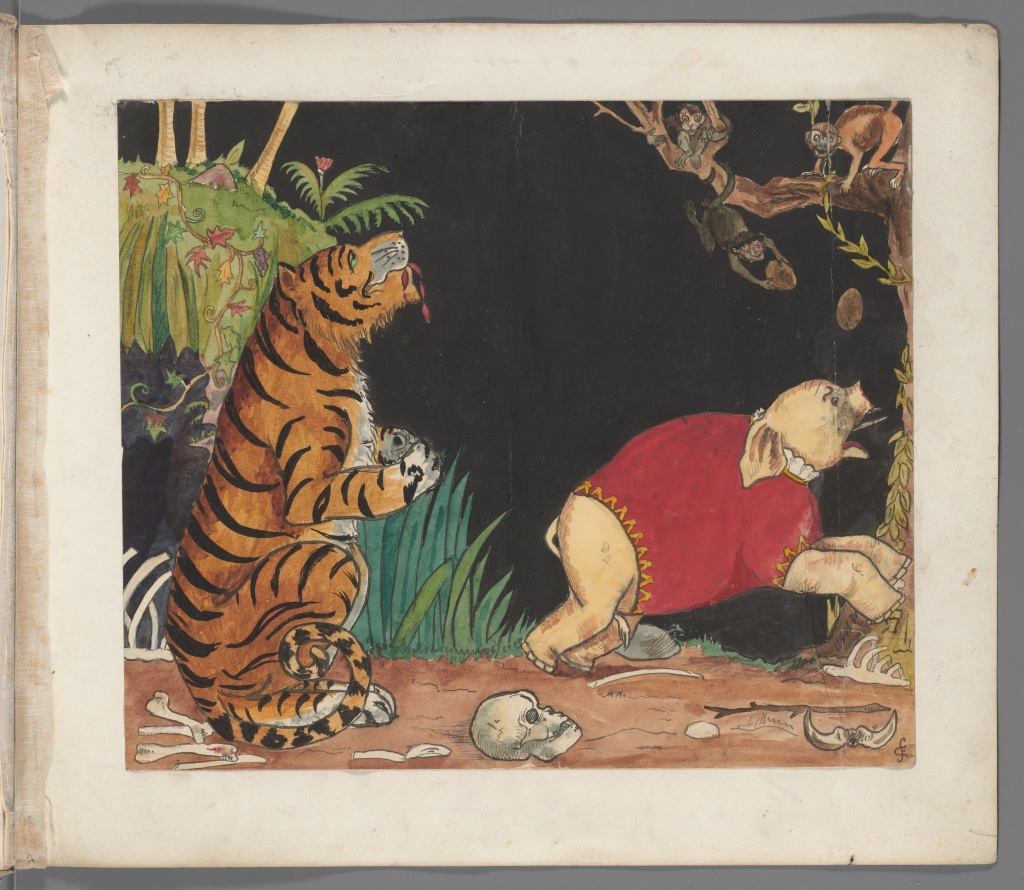

JAS: Not so much ‘eureka’, but a thrilling series of moments in my more recent research was exploring the Somerville and Ross archive in the Houghton Library, Harvard. When reading the manuscript drafts of Somerville and Ross’s The Real Charlotte I was surprised to come across stanzas from the Californian cowboy poetry of Joaquin Miller alongside descriptions of Dubliner Francie Fitzpatrick falling off her horse into a furze bush. This started me on a search into American material which I am still pursuing. In addition, seeing Somerville’s sketches of the characters of this novel in the margins of the manuscript was like suddenly meeting them in real life – some pictures had been cut out, and I was able to track them down to a scrapbook in the Drishane Archive in Castletownshend, West Cork. I finally met Charlotte Mullen face to face. Also in the Houghton was a gorgeous and hitherto unknown handmade production of Somerville’s best known children’s book, The Story of the Little Elephant Who Wanted a Long Nose (The Discontented Little Elephant). A meticulous and beautiful work with pictures I had never seen before, it made me realise more fully the significance of the book making craft for women writers and artists of this time. [You can read Julie Ann Stevens’ blog on ‘The Mystery of the Disappeared Drishane Archive’ here.]

Q: Irish women’s literary history of the period 1880 to 1920 seems to have gained some momentum in the 2000s. The year 2007 saw the publication of both your monograph The Irish Scene in Somerville and Ross and Heidi Hansson’s study Emily Lawless 1845-1913: Writing the Interspace. Considering the challenges involved in publishing single-author studies on writers who are not anchored in the canon, these publications were tremendous achievements that demonstrated that there is an academic market for such books. Both were published by Irish presses (Irish Academic Press and Cork University Press, respectively). What are your thoughts on the contribution of Irish presses to the study of Irish women’s literary history? And do you see (or foresee) an interest in Irish women’s writing of earlier eras moving beyond the confines of Irish readers and Irish Studies researchers?

JAS: I can only speak as an outsider to the publishing industry, but it seems to me that Irish academic presses need to be selective in order that they might show a variety of kinds of works on their lists. As a result, it may suit writers working in a particular area to seek out more specialised publishers. However, smaller publishers or trade presses do not always have the academic recognition which universities require for their faculty. Moreover, writers not anchored in the canon do not have the same name recognition outside of the country and this is an additional challenge. Researchers working in Irish women’s literary history have surmounted this difficulty somewhat by revealing the significance of lesser known women writers in relation to the fabric of Irish writing as a whole. Although Somerville and Ross are fairly well known, I still tried to do this in my publications. I wanted to show the broader reach of their work. As a result, and when working on my first book in particular, it often seemed like I was juggling multiple issues – not just because of the allusions and parodies being introduced by such artful writers/artists but also because of my intent to show the pattern which the web of materials produced. I wanted to show how the pattern would tell us something about the kind of terrain within which the writers operated.

As we look forward I wonder if people working on Irish women’s writing of earlier eras might seek to broaden the appeal of their research. Already researchers in the IWWN are showing how the study of groups of writers reveals the movement of ideas, the interaction of diverse areas of thought, and important transnational connections. Perhaps we might think even more about how some of the arguments introduced at this time regarding female sexuality or power relations and gender might be shown to have vital significance to today’s arguments in relation to women’s writing. Already we are seeing publications which seek to offer new avenues of approach to Irish writing. To appeal to the wider interests we might begin to show even more how Irish women’s writing of earlier eras offers particularly rich material for anyone working in women’s writing today.

Q: What book, play or poem/poetry collection written by an Irish woman written between 1880 and 1920 do you feel deserves more attention and respect, and why?

JAS: Because I have been immersed in children’s books for the past while I will mention the neglected artist-writer, Sophia Rosamond Praeger, and her series of children’s books published at the turn of the twentieth century. Although better known as a botanical artist and sculptor, she also wrote and produced wonderfully amusing and beautiful children’s books. Some of these works contribute significantly to the recording of Irish material culture while the fantastical creations in books like The Adventures of the Three Bold Babes (1897) recall her grandfather Robert Patterson’s interest in zoological study (a member of the Belfast Natural history and Philosophical Society, he produced science textbooks in the mid-nineteenth century). As a suffragist Praeger contributed material to the Suffrage Atelier, and she also wrote poetry – some poems record northern Irish dialect and turns of phrase. Her work has been examined mainly in the context of Irish art, and I think that study of her books and writings alongside the art would reveal the wider reach of her production and its significance in relation to Irish women’s creative works.

Q: You’ve uncovered a rich array of archival material, in particular by demonstrating Somerville and Ross’ engagement with popular and elite forms of art and literature. In what ways has your attention to visual culture led to a new understanding of their texts?

JAS: Visual images inspire words just as a text may give rise to mental pictures. Sometimes the visual stands in place of words. As a result, attention to visual culture can reveal another dimension of an illustrated work and can inspire new ways of thinking about text. In addition, the period when Somerville and Ross were writing sees the development of the roman d’atelier and the künstlerroman, and so there is a rich discourse on pictures and the role of the visual artist in some fiction of the time. Because Somerville and Ross go one step further and add actual pictures to their text, this discourse becomes amplified in a most interesting way. Finally, I would say that discussion on collaboration becomes more complex when one of the co-authors contributes images as well as text to the mix. And when one co-author serves as a model for the other in the creation of the visual parts of the book, things get even more intriguing.

Q: In your role as Research Convenor for the School of English, to what extent have you been able to integrate your research into teaching? If so, how do your students respond to the works of writers such as Somerville and Ross, and to the rich relationship between text and visual culture?

JAS: My research crosses different areas, and as a result it has been useful in working with graduate students interested in diverse material, from Irish women’s publishing history to supernatural fiction to children’s literature. For instance, I was a member of the examining committee for Marian Therese Keyes’s 2010 PhD dissertation on Anna Maria Fielding Hall. More recently I examined early PhD work by Anindita Battacharya on the supernatural in Irish and Bengali children’s literature. I have integrated my research into postgraduate teaching in part by dividing my time between Irish women’s writing and children’s literature. When I served as Director for the Centre of Children’s Literature and Culture in St. Patrick’s College and then in Dublin City University, I found myself increasingly relying upon my work in the visual because my research could offer new perspectives on the area in children’s literature. Moreover, picture books and illustrated fiction appear to interest students at graduate level particularly because they often come from areas such as education or librarianship. Irish writers and artists also tend to attract students at this level, and I have worked on courses with Irish (or Irish- related) women artists/writers from 1880-1920 like Sophia Rosamond Praeger and Pamela Colman Smith. I have also worked with graduate students on Irish women writers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who cross from adult to children’s material – the Keary sisters, Flora L. Shaw, Emily Lawless, Mrs. Hall. I would see room for development in this area.

Image from Somerville’s best-known children’s book The Story of the Little Elephant Who Wanted a Long Nose (The Discontented Little Elephant) featured in Stevens’ book Two Irish Girls in Bohemia.

Q: In addition to your research interests in women’s writing, you have also developed a strong expertise in children’s literature. Your chapter on ‘The Little Big House: Somerville and Ross’s Work for Children’, for instance, offers a reading against the grain of canonicity by focusing on collaboration and blurring the boundaries between what were once deemed to be mutually exclusive categories such as ‘highbrow’ and ‘popular’, literature and art. What has such a perspective opened for you in your research trajectory?

JAS: I do not consciously ‘read against the grain of canonicity’. Instead, I tend to follow the lead of my subject and let it take me where it will. Popular comic writers like Somerville and Ross give someone like me a rather wild chase – across fields and down all sorts of boreens. Of course, crossing different terrains, or leaping from one category to another, can be challenging as each place has its own demands. Children’s literature, for example, has its own set of arguments and a distinct theoretical framework with which one needs to be familiar if entering the arena. At the same time, coming from another area can add immensely to the discussion at hand. Perhaps my early work on the short story made me more open to the possibilities of so-called minor literature. Whatever the case, this perspective has allowed me to enter into areas which I would not have foreseen (such as the ghost story or children’s books) and to explore more deeply areas which I have always wanted to examine (such as art history and visual discourse).

Q: What research project are you currently working on and what do you consider to be the key challenges of Irish women’s literary history at the moment? In other words, what old and/or new questions are driving your research at the moment?

JAS: I am very interested in female creativity and its expression in the late nineteenth century. I have been looking at the impact of women writers/artists/actors’ interactions in Paris on Irish and Irish-American production. I have also been exploring international connections of certain Irish and Irish-American women of the period. I think the challenge for me and possibly for others working in Irish women’s literary history is to show this important reach in Irish women writers’ production while maintaining focus on that which is personal and intimate about Irish reality. A more practical challenge can be access to some materials. Illustration and sketches by lesser known female artists can be difficult to locate and oftentimes the writings and letters of some of the women writers of this period can be scattered across multiple archives.

Research Pioneers 11: Julie Anne Stevens #IrishStudies

Tweet

To reference this blog:

Harvard style:

Stevens, Julie Anne. (2020), ‘Research Pioneers’, Interviewed by Anna Pilz and Whitney Standlee for Irish Women’s Writing (1880-1920) Network, (August, 2020). Available at: https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/2020/07/17/research-pioneers-11-julie-anne-stevens/ (Accessed: Date)

See our full guide here.