Research Pioneers 13: Kathryn Laing

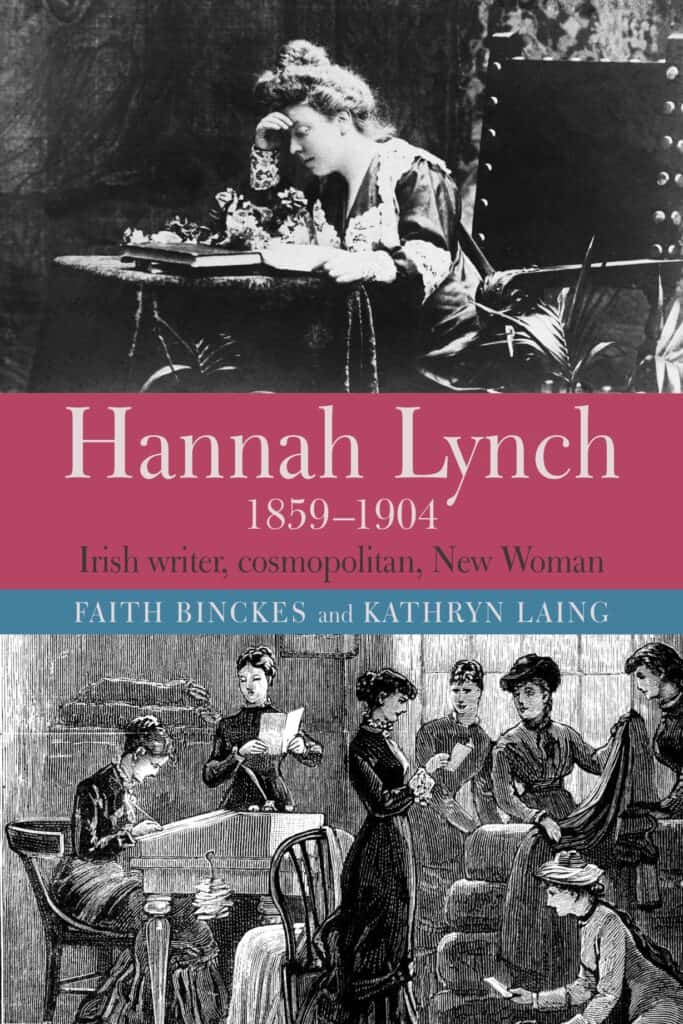

Kathryn Laing has a career-long research expertise in women’s writing and Irish women’s writing in particular. Her wide-ranging publications focus on the works of Hannah Lynch, Rebecca West, Virginia Woolf, and Edna O’Brien. Together with Faith Binckes, she’s co-written the study Hannah Lynch, 1859-1904: Irish writer, Cosmopolitan, New Woman (2019), and, with Sinéad Mooney co-edited Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives (2020). You can read the introduction to that volume here.

Her service to the field most recently bore fruit in the co-founding of the Irish Women Writers Network 1880-1920 that has the ambitious aims of bringing together scholars with common research interests, providing a virtual platform that offers research and teaching resources, and making the latest research findings accessible to students in the form of a new network-associated series of full-length works issued through EER publishing.

This is the thirteenth interview in the Research Pioneers Series conducted by Anna Pilz & Whitney Standlee. Our first interview with John Wilson Foster is available here, Heather Ingman and Clíona Ó Gallchoir is here, James H Murphy is here, Heidi Hansson is here, Lucy Collins is here, Gerardine Meaney here, Margaret Kelleher here, David Clare, Fiona McDonagh and Justine Nakase here, Elke D’hoker here, Mary S Pierse here, Julie Anne Stevens here and Tina O’Toole here.

Q: What initially drew you to the study of Irish women’s writing of this period?

KL: I have always been attracted to ‘the lives of the obscure’, in Virginia Woolf’s words, and especially interested in this turn-of-the-twentieth-century period, having started my postgraduate work on modernist women writers including Virginia Woolf and ending with a focus on the early writing of Rebecca West. Later I turned my attention to Irish women writing and publishing from the mid-twentieth century – Edna O’Brien, Kate O’Brien, Elizabeth Bowen, Mary Lavin. I was drawn back to the late-nineteenth century specifically by what I call the ‘Hannah Lynch project’ which was launched, serendipitously and fortuitously, through an invitation from Faith Binckes to develop the research she had started on this completely unknown writer listed as such by the Dictionary of National Biography. We began with very few details about Hannah Lynch and in our quest to discover more about what she published and the contexts that shaped her as a writer, we realised that her life, publications and indeed active participation in the Ladies’ Land League intersected with an array of equally intriguing female literary contemporaries whose names were just that, names. Existing biographies and access to their publications or scholarship that drew attention to them were very limited but tantalising. It was like seizing on a stray thread and discovering a tapestry. There is a great deal of new scholarship paying attention to the work of some of Lynch’s contemporaries in press or published – these are exciting times.

Q: Which researchers helped and influenced your own work?

KL: In relation to the Hannah Lynch project, recent recovery projects and feminist scholarship focusing on turn-of-the-twentieth-century Irish women writers provided us with insights into what was still unknown within the field and inspired us with innovative methodologies for uncovering and delineating the oeuvres of particular authors. Indeed, each of the contributors to your Research Pioneers series of interviews has been influential and inspiring via their publications and often through conversations, both formal and informal. There are many others, too, whose innovative scholarship has opened up the field further and identified ways in which new narratives about this period need to be formulated. It was at Maureen O’Connor’s key ‘Irish Feminist Thought’ conference in 2008, for example, that our Hannah Lynch project was launched and henceforth encouraged and supported. Your own co-edited volume has provided a foundation and springboard for scholars working in this field. Faith Binckes’ expertise in modernist periodical publications informed my own interest in periodicals and print cultures, now an area of rapid growth in Irish studies. I am following Elizabeth Tilley’s work in this field, as well as Stephanie Rains, with great interest. Alexis Easley’s work continues to be foundational to shaping my own perspectives and her support for the Network continues to be invaluable, too. Faith’s interest in ‘affect’ and ‘affect theory’ helped us to develop our understanding of the essential female-centred networks that promoted struggling writers like Lynch and we were both inspired by Ana Parejo Vadillo’s work on London literary salon culture as well as Catherine Clay’s methods of mapping later feminist literary networks, particularly those associated with the feminist monthly magazine, Time and Tide.

The generosity of scholars who shared material they had painstakingly retrieved from the archives not only contributed to filling in some of the many blank spaces in Lynch’s literary life, but also shaped the direction of some of my later research. I am thinking of Adrian Frazier who sent us all his archival notes on Mabel Robinson, the sister of Mary F. Robinson; both women were prominent and powerful salonnières who supported and promoted Lynch. And Tadhg Foley’s enthusiasm and support for our research right from the beginning, as well as his own encyclopaedic knowledge and extensive networks with scholars willing to share their expertise with us, provided a sense of intellectual community and contributed to this most recent project of shaping more formally such a community through the Network.

Q: Researching little-known authors with scattered or no archives can be a challenge when it comes to piecing together biographical and literary contexts. Sometimes we don’t even know what a writer looked like, because there are no photographs to be found. For example, after many years of working on and extensively researching the Irish author Hannah Lynch, you finally unearthed a photograph of her. Can you tell us about this particular ‘Eureka moment’? Are there any other comparable moments from your research experiences?

KL: This is a wonderful question. Working on little-known authors, and there are still so many turn-of -the-twentieth-century Irish women writers in this category, often means constructing an archive first, even if this remains a virtual one: a textual record of where archival sources have been located, transcribed or copied, and embedded in the narrative under construction. In this way, volumes like the Hannah Lynch book become an inevitably incomplete archival catalogue for a writer whose correspondence is scattered across a variety of other archives or lost completely, and whose manuscripts are missing. Archival research involves a great deal of literary detective work following hunches, ending up on many a wild goose chase, dead ends and sometimes a ‘eureka moment’. Serendipity so often plays a part, too. Of course, the internet broadly and digitisation specifically has transformed the way in which material can be traced and has made possible what would have been impossible even a decade or two ago.

The story of the photograph is the best kind of twenty-first century ‘lost in the archives’ tale. It reflects the possibilities generated by technology. Promotion of a conference on the web including a paper on Hannah Lynch initiated an e-mail correspondence with Hannah Lynch’s great nephew, and this in turn led to the sourcing of some family papers and the quest for a photograph. The necessary generosity of family members to share, remember and engage in the quest was imperative, and demonstrated that there are often still surprises that lie in wait in attics. Close to completing the Hannah Lynch volume and, despite having trawled hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles where images of other women writers were often featured, we were no closer to locating an image of her. Family members had all checked through their papers – we were left with only our textual portraits constructed by contemporary writers, observers and, minimally, by Lynch herself. Before the manuscript was sent off, we sent a final request to the family, but it remained the case that no image of Lynch was forthcoming. And then literally at the last moment we received an email informing us that a postcard image had been discovered by a family member who had not been looking for the missing photograph of Lynch at all! We could rewrite our conclusion and, fascinatingly, we had to reappraise our own unconscious construction of Hannah Lynch’s image developed over many years.

NYPL Manuscripts

Archival research and recovery work in general is full of smaller ‘eureka moments’ – even if a transformational event never happens. I could list numerous of these from the Hannah Lynch project: the gaps and missing details about her involvement in the Ladies’ Land League, glimpses here and there in histories and memoirs but no sign of such a significant and formative period in her own writing, none listed in the limited bibliographies of her writing, none that our trawling had revealed. And, of course, this work existed and its recovery formed a vital missing link in the story we were composing. These short fictions were concealed in non-digitised nineteenth-century periodicals and nationalist ‘story papers’ stashed in manuscripts rooms rather than sharing the shelves with other contemporary newspaper publications. Tracing the latter required following a trail of hints and possibilities, and would have ended in a dead end had it not been for the generosity and persistence of librarians in the Reading Room and the Manuscripts Room in the National Library in Dublin who joined in the search.

National Library of Ireland

It is at this point I want to acknowledge the importance of librarians and archivists in many libraries and cities whose generous knowledge and interest continue to influence my research generally and more specifically helped to shape the Hannah Lynch project in unexpected ways. These include everyone from those who joined in the hunt for lost photographs and missing serialised novels (thanks to the wonderful NLI librarians), to Damien Burke in the Irish Jesuit Archive whose breadth of knowledge and sharing of potentially helpful contacts was as invaluable as the archive itself, and the librarians in the NYPL who were willing to source and photocopy a stash of Hannah Lynch related letters at speed.

McFarlin Library

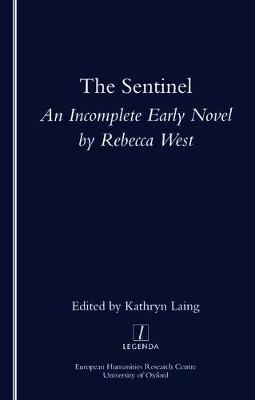

Comparable moments in the archives – absolutely yes. My earliest experience of archival work was as a doctoral student undertaking research on the early writing of Rebecca West (another woman writer who, while now no longer either forgotten or underestimated, still remains to some extent on the margins of various literary canons). In that case there were West archives to visit, all in the United States. The West papers, housed in Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa, share space with an astonishing array of writers: James Joyce and William Trevor, to name two. The riches of the West archive, explored and relished by many a West scholar, was an exhilarating and daunting place for a postgraduate student with no archival experience to start. Armed with a pencil, paper, access to photocopiers and yet again extremely generous and helpful archivists, there was much territory to cover and uncover. To make a long story shorter, this ‘eureka moment’ was also the most serendipitous. My research week was at its end and I had a plane to catch. With a little time left to savour and explore one last box folder, more as a whim than necessity, the chunky manuscript I extracted from a folder identified as authored by one Mabel Lancashire soon had me leaping to my feet and dashing across the room to consult Lori Curtis, the curator of Special Collections at that time. It was a shared ‘eureka moment’. Handwriting, the names of characters, the story itself suggested this was in fact written by the young Rebecca West – a missing link in the story of her own involvement in the suffragette movement and of her feminist literary apprenticeship. It was a long novel and there was no time to read it. I had to catch a plane – how could I be sure? It took some time to verify my initial recognition that this was something special. It also meant rethinking my thesis! The painstaking act of identifying, verifying and transcribing the unfinished novel in its entirety was dependent on the support of the literary estate and the continuing generosity of archivists in Tulsa, and Lori Curtis in particular, who advised and supported me in a variety of ways from photocopying endless pages to poring over West’s writing when I could not transcribe the photocopies. Work in the archives is solitary, slow, laborious and sometimes astonishingly exciting, but it is also communal and connective. Lori Curtis noted on the launch of the publication of my scholarly edition of West’s unfinished novel, The Sentinel, that it had been like the birth of a baby. In this way, the generosity and expertise of archivists and librarians are like the midwives of archival discoveries, upon whom researchers are always dependent.

With such an extraordinary experience so early on in my academic career, getting lost in the archives, digital and even better the old-fashioned kind, and the possibilities this offers to rethink existing narratives has always been for me the best kind of research.

Q: 2019 saw the publication of your co-authored book with Faith Binckes on Hannah Lynch, who was both a cosmopolitan and New Woman writer. Drawing on extensive archival material that brings to light Lynch’s embeddedness in a web of European connections and influences, you have opened up further avenues for research into women writers from Ireland. In what ways has working on this project affected your thoughts about Irish women’s writing around the turn of the twentieth century? Were networks of women as important to amplifying women’s voices and publicising women’s concerns then as they are now?

KL: Reading correspondence between Katharine Tynan and Jane Barlow in the Manchester University Library archive highlighted for me early on in our research the power and significance of networks for these women writers. I was fascinated to discover pages of publishing advice from Tynan about which magazines or periodicals to approach, who paid the most, which editors were difficult or enabling and so on. These were accomplished and serious writers who treated their work as a profession and each other as professionals. And we discovered Tynan’s active support for Hannah Lynch, providing her with contacts in London so she could procure a highly desirable reader’s ticket at the British Museum, for example. The late nineteenth-century literary salon, as we know, was a vital space for these aspiring writers to find patrons or publishers or to create further connections. Such networking and collaboration was often fraught and competitive, too: our discoveries also revealed that Tynan not only supported her female contemporaries but expected support in return. She was stung by Lynch’s spoof on the lionising of the yet to be famous W. B. Yeats at her Clondalkin literary salon and indignant that Rose Kavanagh was favoured over herself for the position of editor of the Irish Fireside.

Hannah Lynch Book Launch, IASIL Conference, 24 July 2019. Names from left to right: Kathryn Laing, Michael Counahan (grand-nephew of Hannah Lynch), Faith Binckes

I think these late nineteenth-century women writers generally teach us the value and, unfortunately, the necessity still of forging our own support and promotion networks. They also offer insight into the challenges that remain to be navigated. There are important developments in this field: Caoilfhionn Ní Bheacháin and Angus Mitchell focusing on historian Alice Stopford Green affords us one example, and Deirdre Brady’s forthcoming monograph, Literary Coteries and the Irish Women Writers’ Club (1933-1958), offers another.

Q: When Margaret Kelleher launched your book on Lynch at IASIL in 2019, she beautifully highlighted the way in which the book opens out to connecting narratives of individual writers and the collective as well as showcasing the way in which networks work between women. Considering the fact that the book itself was a collaborative effort, to what extent has the study of Lynch confirmed and strengthened your own collaborative profile and ambitions for collectives?

KL: Well, as you know, the forthcoming Network symposium with its focus on collaborations is also an experiment in such a collective. The Network Team is powered by established scholars and postgraduate students with the aim of developing various platforms for new voices and new areas of scholarship that have often been overlooked. Such aims are at the forefront of the symposium, providing a platform for collaborative research as well as a focus on sometimes interdisciplinary and international collaborations and networks that have opened up the field. The Team are also all involved with setting up the conference as well as selecting and editing contributions to a double issue in the journal English Studies in 2022. This project, and indeed the Network and its digital platform, is for me particularly inspired by the Modernist Archives Publishing Project. The project has its origins in shared research passions that became a carefully theorised model of teamwork, written collaboratively by the six members of the project (Scholarly Adventures in Digital Humanities: Making the Modernist Archives Publishing Project), and resulted in a prototypical database that, amongst other things, fosters support and the development of research and digital skills opportunities for postgraduate students.

Q: In 2016, together with Dr Sinéad Mooney, you launched the Irish Women’s Writing Network with a symposium of keynote speakers and presentations at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick. How did the idea for the network come about?

KL: It was recovering Lynch’s literary and publishing networks that crossed from Dublin to London and Paris in collaboration with Faith while simultaneously forging our own scholarly networks that in part inspired this idea. Generating research that leads to intellectual and collaborative support networks is especially important for scholars working on marginalised or neglected writers, because these are more often than not women writers who have been unjustly overshadowed by their male contemporaries and the vagaries of the literary canon. Sinéad Mooney and I had already worked together along with Maureen O’Connor on another Irish woman writer who was neglected at the time, Edna O’Brien. As is often the case, that recovery project/research and collegial network began with an informal conversation while we were all waiting for a lift to the ground floor at NUIG. Hardly knowing each other at the time, we agreed that O’Brien’s writing deserved more scholarly attention. The result was twofold: a conference, followed by a collection of essays. In retrospect, this was also the basis for a nascent intellectual, collegial network which has continued to bear fruit: most recently, Maureen has completed a monograph on Edna O’Brien and the Art of Fiction.

Discussing shared research interests, the possibilities of sourcing funding for new research projects in Ireland and the UK (where Sinéad was based at the time), and conversations about neglected women writers grew into an idea for a symposium and formalising our efforts to facilitate recovery projects and networks.

Q: With a wide-ranging publication profile, you have developed a particular focus on the period from 1880 to 1920 that is also the focus for the IWWN. What makes this period particularly enticing and deserving?

KL: This period is irresistible for me and, in view of the first two decades of the twenty-first century, astonishingly contemporary. The dizzying changes and uncertainties that prevailed at the fin de siècle were combined in the era with the possibilities for cultural, political and social transformations.

Irish women’s writing and publishing has been particularly neglected in this era; marginalised as we know by the mainly male-dominated narratives of the Irish Literary Revival and the modernist canon. This considerable body of writing is now enjoying long overdue attention by scholars working in the fields of nineteenth century, fin de siècle and modernist periodical and print culture studies. This multi-disciplinarity is opening the field further, provoking new modes of enquiry and bringing to light new narratives about this period and the centrality of women’s writing, publishing and networking to these narratives.

Q: What book, play or poem/poetry collection written by an Irish woman between 1880 and 1920 do you feel deserves more attention and respect, and why?

KL: This is a challenging question, partly because there are still so many writers and their works that await excavation and recovery, and partly because of recent scholarship identifying and addressing the aporia in narratives around women writers of this period and in some cases making available forgotten works. On the one hand I want to say writers like Katharine Tynan, Rosa Mulholland, Emily Lawless and (unsurprisingly) Lynch, whose multifaceted oeuvre certainly deserves more attention. Yet I am also aware of great scholarly work in progress on these writers. And then there are those on my literary radar – Clotilde Graves, for example, and Gertrude Elizabeth Blood (Lady Colin Campbell) – whose unconventional lifestyles have inevitably attracted attention but whose diverse work as dramatists, short story writers and novelists as well as journalists and editors deserve further critical recovery. They are also ‘down the road’ from Limerick, as it were. Gertrude Elizabeth Blood was born in County Clare and Clotilde Graves in County Cork. Both have received some valuable critical attention, mostly in relation to G. B. Shaw, but the range of their writing and their contributions to shaping the contemporary literary and feminist landscape awaits further exploration. I don’t know enough – I want to read more!

Q: In association with the IWWN, you and Sinéad Mooney have started a new collaboration with Edward Everett Root Publishers that will focus on the latest research in the field. As general editors, you are running two series: Key Irish Women Writers and Irish Women Writers: Texts and Contexts. What prompted this initiative? Can you tell us a bit about these exciting developments and the audience you have in mind for these series?

KL: This really is an exhilarating moment for scholarship on marginalised women writers broadly, and Irish women writers of this period specifically. When Faith and I started to explore the possibility of publishing a monograph on Hannah Lynch, presses were interested but pointed out there was no market for such a publication. This has changed and continues to develop. Publishers are at last starting to recognise the value and necessity of recovering women’s voices. Arlen House has always been supportive, Tramp Press has established a recovery series, and the Swan River Press is reissuing in highly aesthetic formats an intriguing range of short fiction by late nineteenth-century women writers.

The initiative for our two series was prompted by a conversation with the publisher John Spiers of EER relating to the preparation of our edited collection in Pilar Villar Argáiz’s Studies in Irish Literature, Cinema and Culture series. Having launched the highly successful Key Women Writers series published by his press Harvester in the 1980s, a similar project with a focus on Key Irish Women Writers seemed not only timely but long overdue.

Delighted with the proposal that we pursue this project, Sinéad and I were equally excited to have the opportunity to develop our ideas for the Texts and Contexts series, very much in tune with the ideals of the Network. This series is not only aimed at recovering forgotten writers but also acts as a quest for ways in which to make their work accessible to a wider and more diverse range of readers. The Texts and Contexts series, in particular, helps to realise this aspiration. These edited volumes will introduce readers to writers and their work that are more than likely unfamiliar and otherwise inaccessible. The first volume to appear in this series – Elke D’hoker’s brilliant introduction to Ethel Colburn Mayne, New Woman writer, proto-modernist, contributor to and briefly sub-editor of the Yellow Book – is the perfect example of what makes this invaluable for scholars, students and interested readers alike. One wonders why she isn’t much better known! The volume includes a selection of her short fiction that overlaps with and anticipates Elizabeth Bowen’s and Molly Keane’s later writings and would make ideal teaching companions with fiction by Katharine Mansfield, Henry James and George Egerton. The second volume in the series offers a collection of fiction, non-fiction and poetry by Rosa Mulholland, edited and introduced by James H. Murphy. It is exciting to see Mulholland’s work featuring in new anthologies and studies in recent years. Look out for the third volume (my own), which is based on two fascinating stories about the Ladies’ Land League that Hannah Lynch published in 1884/5 and 1889. These stories, and those by other writers awaiting discovery, are changing the narratives around this organisation and the period itself.

Both series are aimed at scholars, students and interested readers in general. The Key Irish Women Writers series offers short scholarly but accessible introductions to the works of selected authors and a survey of critical approaches to their writing as well as outlining new critical directions that might be explored in the future. Heather Ingman’s brilliant Elizabeth Bowen volume has just been published, and acts as an invaluable addition to the flourishing field of Bowen scholarship. We look forward to the publication of Clíona Ó Gallchoir’s volume on Maria Edgeworth, Aintzane Legarreta Mentxaka’s on Kate O’Brien, and Eibhear Walshe on Jane Wilde later this year.

Q: If we were to take a flight of fancy, what would the network look like 10 or 15 years from now? What is your vision for this collective of early career and senior scholars?

KL: The plan of course is that the collective will continue to grow and develop. The hub of the Network, already a vibrant virtual space for researchers from around the globe to connect and exchange ideas and information, is the website with social media platforms, Facebook and Twitter as supports and key dissemination portals. This is a multifaceted platform, developed in various ways by the Network Team and in particular benefitting from the digital expertise of Deirdre Flynn and contributions from the growing body of Network members. For example, the website already hosts regularly posted blogs where early career and senior scholars alike can publish short pieces on new research, recent ideas, discoveries, or new projects. These are invaluable resources, especially on writers who feature little or not at all in mainstream criticism. In developing the website we have collectively begun establishing the foundations of an archive of knowledge about marginalised or neglected Irish women writers and building a database for storing and sharing this knowledge. I like to imagine that in 10 or 15 years this rich, open access repository will offer even more resources that are searchable and enable both scholars new to the field and those who are experts to find and access the resources required to expand our knowledge of Irish women writers and their works exponentially. There is much more work to be done and promising times ahead!

To reference this blog:

Harvard style:

Laing, Kathryn (2021), ‘Research Pioneers’, Interviewed by Anna Pilz and Whitney Standlee for Irish Women’s Writing (1880-1920) Network, (May, 2021). Available at: https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/2021/05/18/research-pioneers-13-Kathryn-Laing/ (Accessed: Date)