Rockmahon, Blackrock Co. Cork: Family home of Novelist and Short Story writer Ethel Colburn Mayne (1865-1941)

Elke D’hoker, University of Leuven

This is Rockmahon[i], one of the original nineteenth-century properties along Castle Road in Blackrock, Cork. Built around 1820, the house is adjacent to the river Lee. It faces north towards the docks and the Tivoli hills and east towards Blackrock Castle. From 1894 to 1905, Rockmahon was the home of the writer Ethel Colburn Mayne, whose literary career took off in 1895 when a story of hers was accepted in The Yellow Book. Although Mayne is little known today, she went on to build an impressive and versatile career as a novelist, short fiction writer, biographer, reviewer and translator.

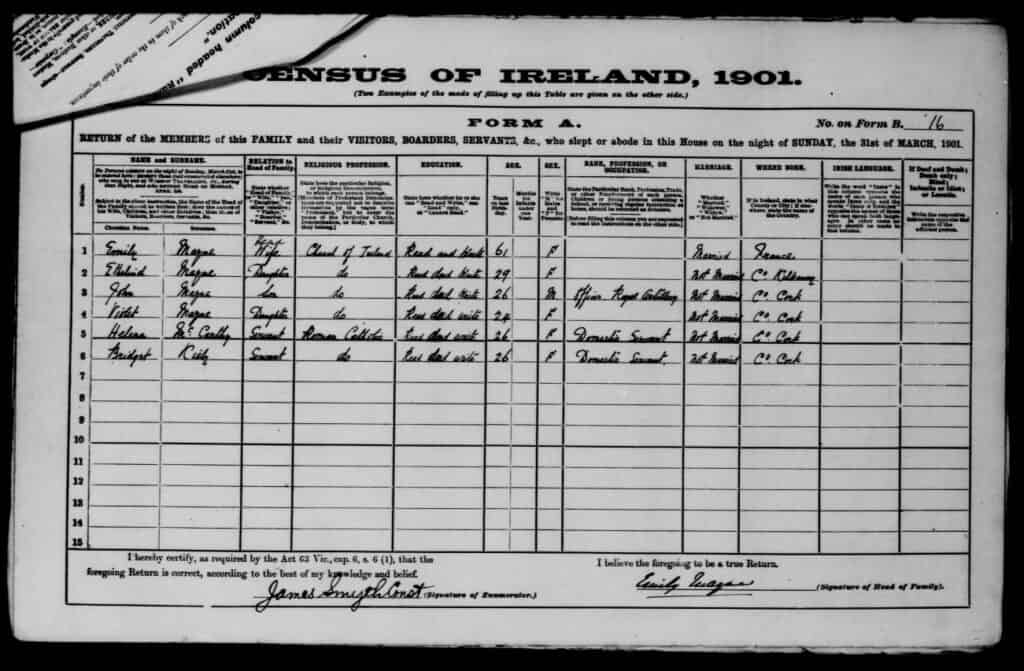

Ethelind had been born some thirty years earlier, in 1865, in Johnstown, County Kilkenny. Her father, Charles Edward Bolton Mayne, was a district inspector in the Royal Irish Constabulary and the family followed him around on his different postings: Kinsale, Skibbereen and finally Cork, where he was appointed resident magistrate in 1882 (Waterman 1999). The family seems to have lived in downtown Cork for some years, on Tuckey Street and at College View Terrace on Western Road. Following Charles’ move up the promotional ladder, the family moved to this more upscale property in Blackrock. The 1901 census records Ethel living in Rockmahon together with her mother, Emily (born Sweetman), her younger sister Violet and her younger brother John. Of the eight children of the family, only four survived into adulthood. The census also records the name of two servants: Helena McCarthy and Bridget Kiely.

This census document records the names of the people who had slept in Rockmahon on the 31st of March, 1901. Mayne’s father had presumably been absent and Mayne’s mother saw fit to detract 5 years from the age of her two daughters.

Although Mayne may have started writing before 1894, it was from her family home in Blackrock that she sent out her first work to literary magazines in England. In April 1895 a first story was published in Hearth and Home. It was quickly followed by “A Pen-and-Ink Effect” in the July edition of the prestigious Yellow Book and by “Her Story and His” in Chapman’s Magazine in November. Her publication in The Yellow Book, and the correspondence with its editor Henry Harland, also led to Mayne being offered a job as sub-editor of The Yellow Book and she left Cork for London on the 1st of January of 1896. She would later write “as the Irish boat-train reached Euston at the grim hour of 6 a.m. [Harland] had also ordered breakfast, but ‘reassured’ me (as he said) as to his coming to meet me” (Samuels Lasner 2006, 18).

Her position at The Yellow Book gave Mayne the opportunity to meet with the notable literary figures of the day and to benefit from Harland’s teaching. It came to an end sooner than she wished, however, and Mayne had to return to Cork. Some of the reluctance she may have felt at having to return to her parents’ home may have found its way in the short story “The Letter on the Floor”, where the protagonist ponders, “Anyhow, she’d have to go. These rooms were too expensive, now she had so little work. Her ‘post,’ with its small monthly salary, had gone with him. Money came from home, but home was not so rich that they could send enough to make up the deficiency; unless she could get lots of other work, she’d have to leave not only these good rooms, but London” (D’hoker 2021, 154)

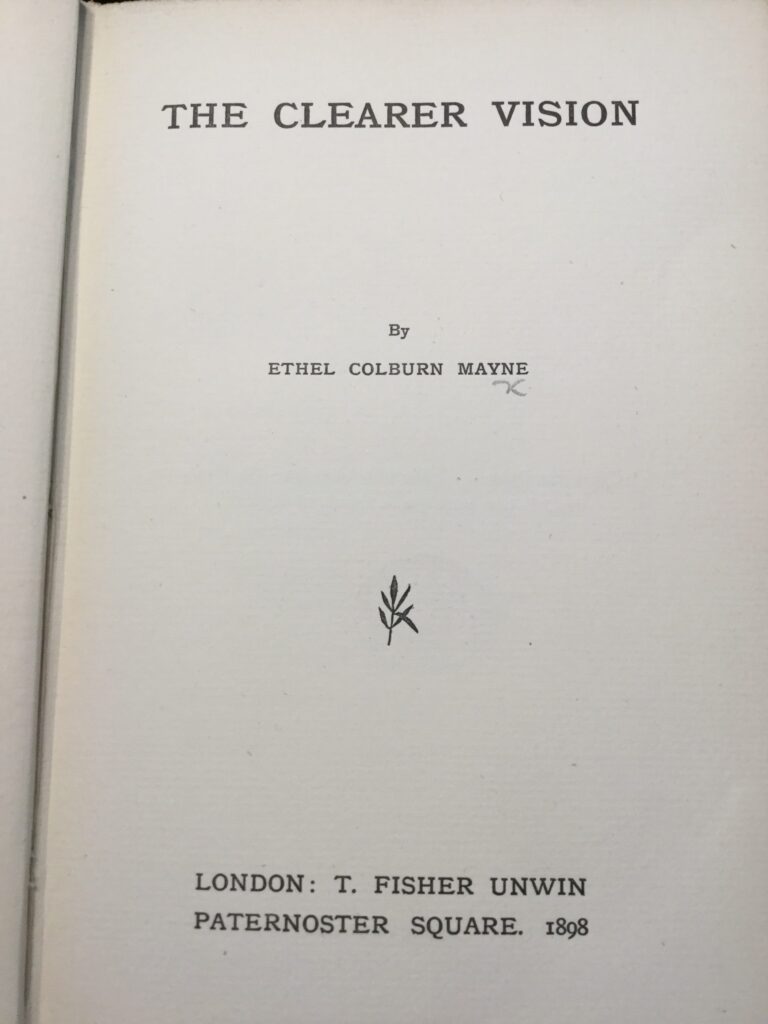

Still, back in Rockmahon, Mayne continued to write and a first collection of short stories, The Clearer Vision, was published by the London publisher T. Fisher Unwin in 1898. It was followed by the novel Jessie Vandeleur (Allen 1902), which relates the fortunes of a spirited Anglo-Irish girl who comes into money and moves to London with her mother. Moving about in the artistic circles of Decadents and Aesthetes, she becomes a celebrated writer herself, but makes some problematic moral choices along the way. Jessie Vandeleur did not itself become the breakthrough Mayne had hoped for and she found it difficult to get her fiction published, even though she was taken on as a client by C. F. Cazenove of The Literary Agency of London. Her letters to him from Rockmahon speak of her tenacious but often fruitless attempts to get magazine editors interested in her stories or to find a publisher for her novel.[ii] Her being in Cork, outside of London’s literary networks, certainly made the process more difficult. As an Anglo-Irish Protestant, Mayne had no easy access to the circles of the Irish Revival either. On the 1st of December 1904, she wrote to Cazenove: “Do you know the address of any of the Celtic Renaissance magazines? The magazines that are published in Ireland, I mean–but not those which are written in Celtic! I ask this because I thought that possibly that little article of mine, “A Song-Recital” [about the renowned baritone Denis O’Sullivan] might suit some one of them. There are several Catholic-Irish things, I know; but I haven’t the least idea how to approach them.”

In 1905 Mayne’s father retired as a resident magistrate and the family left Rockmahon for London. Mayne’s mother had died three years previously and her brothers were in the military, but Mayne and her father moved to a ground-floor flat in Cecil Court on the Hollywood Road in South Kensington. Once in London, Mayne’s career picked up, probably as a result of meeting with editors, publishers and other writers to whom she may have been introduced by her good friend Violet Hunt, or by acquaintances from her Yellow Book experience. Her second novel, The Fourth Ship, was published in 1908, and the short story collection Things That No One Tells in 1910. Mayne also found publication opportunities in the new modernist little magazines as well as in mainstream magazines like The Westminster Gazette, The Pall Mall Magazine and Vanity Fair. She also established herself as a translator from German and French and secured a considerable reputation as a biographer, with a two-volume biography of Byron as one of her greatest successes.

Though Mayne had left Ireland behind, she continued to consider herself as Irish. Her letters bear frequent evidence of this (D’hoker 2021, 4). And in the recollections of friends or acquaintances too, Mayne is referred to as an Irish writer. In the introduction to one of Mayne’s stories in the anthology Great English Short Stories, Christopher Isherwood praises her “quite unladylike Irish wit” (1957, 250) and in her autobiography The Goal, Phyllis Bottome introduces Mayne as “a delightful and witty Irish writer” (Bottome 1962, 19). Mayne also often returned to Ireland in her fiction: her novels feature Anglo-Irish protagonists and are set for the most part in Ireland. They offer highly interesting portraits of the restricted lives of Anglo-Irish girls and women in late-nineteenth century Ireland, particularly in the naval and garrison towns that Mayne would have come to know so well through her father’s postings. Many of her stories too are set in Ireland or deal with Irish characters, even in such later collections as Come In (1917), Blindman (1919), Nine of Hearts (1923) and Inner Circle (1925).

“The Peacocks” from Nine of Hearts even seems to conjure up Rockmahon, through the memories of middle-aged Alicia, now living in London with her father. The story depicts Alicia’s fraught relationship with her mother, who seems bent on curbing her daughter’s ambition and freedom at every step. It is told through an incident with a peacock, which became Alicia’s special pet and was subsequently disposed of by her mother. Years later, a coverlet with peacocks makes Alicia think of “her blue peacock long ago in Ireland, that knew the hour of tea and never failed to call beneath the window for his cake. […] On the minute square lawn that lay beneath the river-window of the Irish drawing-room, how she had loved to watch the magic of that blue and green! It had been like possessing countless jewels. For the peacock was her own, and by his own election.” (D’hoker 2021, 165)

That small lawn may very well refer to the piece of lawn in front of the bay window on the left side of the house, that runs down to the river Lee. The bigger lawn, in front of the house, is also referred to: “in the mornings, she caught sight of him in the ‘big field’ before the house” (D’hoker 2021, 167). Returning in her mind to her present life in London, Alicia seems wistful for the Irish life she left behind: “Between the shaking-out and smoothing of the coverlet, all this! A scene within a scene, and which more actual? As in some lapse of time and space, she had been there in the old Irish room where from the window you looked out upon the broad fair river and the green lawn where her blue bird used to follow her” (D’hoker 2021, 172). Yet, she is also grateful for the independence she gained in London, after her mother’s death: “And have I been ‘unlucky’? Have I cared always for the things that bring ill-fortune? Well, it has been my own life, anyhow” (D’hoker 2021, 172).

Mayne’s own life was equally independent and courageous for a girl who had grown up in the restricted settings of 19th-century Ireland. Many aspects of that life, however, remain unknown. I would be very grateful for any piece of additional information about either her family and life in Cork or her career in London up until her death in 1941. Above all, of course, I hope that her novels and stories will again find the readers that they deserve.

Bibliography

Bottome, Phyllis. 1952. The Goal (London: Faber).

D’hoker, Elke (ed.). 2021. Ethel Colburn Mayne: Selected Stories (Brighton: EER).

Isherwood, Christopher (ed.). 1957. Great English Short Stories (New York: Dell).

Samuels Lasner, Mark. 2006. “Ethel Colburn Mayne’s ‘Reminiscences of Henry Harland’”, in Bound for the 1890s: Essays on Writing and Publishing in Honor of James G. Nelson, ed. by Jonathan Allison (High Wycombe, Bucks.: Rivendale), pp. 16-26.

Waterman, Susan Winslow. 1999. “Ethel Colburn Mayne”, in Late-Victorian and Edwardian British Novelists: Second Series, ed. by George M. Johnson (Detroit: Gale), pp. 187-201.

Elke D’hoker is professor of English literature at the University of Leuven, where she is also co-director of the Leuven Centre for Irish Studies. Among her more recent publication are the critical study Irish Women Writers and the Modern Short Story (Palgrave, 2016), the edited collection The Modern Short Story and Magazine Culture (EUP, 2021) and Ethel Colburn Mayne. Selected Stories (EER, 2021).

[i] I am grateful to Claire Connolly for takings these pictures of the house on Castle Road in Blackrock, Cork.

[ii] Mayne’s earliest letters to Cazenove are in the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. I am very grateful to Susan Waterman for allowing me to read the transcriptions she made of these letters.

Would you like to submit a blogpost? Check out our guidelines here or email Dr Deirdre Flynn.