The Mystery of the Disappeared Drishane Archive

By Julie Anne Stevens

Research recalls detective work. The scholar follows clues to solve unanswered questions or to reveal forgotten or overlooked information. The archive gives opportunity to track clues, and while one of scholarship’s pleasures lies in this search, one of its compulsions may arise when a repository’s mysterious unknown does not immediately deliver information. Nonetheless, just like the fictional detective, the researcher expects to discover eventually some central source of knowledge if she or he looks carefully enough and with the right eyes.

Yet with research, revelation does not always happen – especially when the archive goes missing.

Established in 1995 by Otto Rauchbauer, the Drishane Archive is the first private literary archive in Ireland. It had been available to scholars visiting the National Library of Ireland from that date and throughout the early 2000s. It consisted of large files with plastic microfiche records that were accessible to all. Ten years later it had disappeared from the Library’s holdings. The files could not be found and apparently no amount of searching in the recesses of Ireland’s central library could bring them to light. They had vanished.

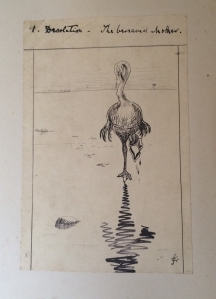

The archive is based on the collection of extensive materials held in Drishane House, Castletownshend, Co. Cork related to the lives and works of Edith Œnone Somerville (1858-1949) and her writing partner Martin Ross/Violet Martin (1862-1915). Co-authors of what some critics have viewed as the finest Irish novel of the nineteenth century, The Real Charlotte (1894), and creators of the popular Irish R.M. stories (1898-1915), Somerville and Ross were second cousins and descended from Chief Justice Charles Kendal Bushe. Their families might be linked to ascendancy homes across Ireland and as prominent writers at the end of nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries they had connections with important writers and artists. Edith Somerville trained as an artist in Düsseldorf and Paris and illustrated many of their works. An excellent sportswoman, she was the first female Master of Fox Hounds in Ireland (1903-1908). She and Martin served as president and vice president of the Munster Women’s Franchise League (1913 onwards).

There are also letters from well known figures: Douglas Hyde on collecting Irish folklore and learning Irish, Rudyard Kipling on the similarities of Ireland and India, Katherine Tynan on the reception of Somerville and Ross in Catholic Ireland, George Bernard Shaw on theatrical matters and Irish affairs. Other correspondents include Lord Dunsany, George Russell, Margot Asquith, Rhoda Broughton, Maurice Baring, Horace Plunkett, Susan Mitchell, Lady Gregory, Harry Clarke, and Stephen Gwynn. Important materials outside of the letters are items such as Somerville’s drawings, Somerville and Ross’s scrapbooks, photographs, manuscripts, newspaper and periodical articles and cuttings, exhibition catalogues, estate management records, and materials related to séances.

For those interested in women’s art and writing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the archive offers significant avenues of research. It provides ongoing commentary on female artists’ training and production as well as the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement. It includes feminist responses to the Irish Revival and Irish and British politics. Violet Martin’s cousin Lady Gregory gave Somerville and Ross a particular interest in people such as W.B. Yeats and George Moore while the Martin family’s home, Ross House in Rosscahill Co. Galway, made them neighbours and friends of the Wildes. Other areas of interest might be women and spiritualism, women and sports (as well as the business aspect of sports), estate and farming practice, religion and philanthropy, women and travel writing, and the suffrage movement.

Edith Somerville’s letters to her family provide vital information about women’s lives at the turn of the twentieth century and some sense of her voice might be provided in one of the letters that Rauchbauer quotes in his excellent overview of the collection. He includes Somerville’s letter to her brother Cameron on 25 June 1908 where she writes about the Great Women’s Suffrage meeting in Hyde Park four days earlier and which she and Martin attended. It was the first large meeting in Britain organized by the Women’s Social and Political Union. The Irish women find a particularly noisy crowd of protesting young men and boys surrounding the platform of the meeting’s most prominent speaker Christabel Pankhurst. Forty-year-old Edith Somerville climbs a railing to get the best view possible:

At last Martin & I wedged ourselves past them & got near enough to hear & see Christabel. She is a very extraordinary girl. She is only about 20, & has just taken an L.L.D. degree in Edinburgh. She is not tall but has a good figure, & a most interesting face. [?] of typical revolutionary, she stood with her head flung back, fronting the crowd dauntlessly, & emphasizing her very able speech with the most picturesque & effective gestures. She has beautiful hands & uses them with amazing effect, & her voice carried better than any of the others. The last act in the performance was a bugle call, after which the multitude lifted up its voice & its hats, & roared ‘Votes for Women!’ I had climbed on to a railing so that I could see away over the heads of the packed masses, & I never saw anything more extraordinary than the effect of the sudden outbreak of men’s straw hats on sticks, & of fluttering pocket hankies when the shout was raised.

When researching for my book on Edith Somerville’s sketchbooks, Two Irish Girls in Bohemia (2017), I tried to find the microfiche of the Drishane Archive that had once been held in the National Library of Ireland. It had disappeared, and it seems that the tendency to overlook women’s writing and women’s history persists well into the twenty-first century. What greater evidence do we need of neglect than this mystery of the disappeared microfiche of the Drishane Archive?

If you wish to study the archive today, you must travel to Castletownshend where Tom and Jane Somerville oversee and maintain this important collection in the family home of Drishane.

Julie Anne Stevens:

‘In writing this article, I wish to thank Tom Somerville of Drishane House for his kind assistance. I also gratefully acknowledge permissions and support from Sir Patrick Coghill and Norah Perkins of Curtis Brown.’

Julie Anne Stevens lectures in the School of English, Dublin City University. From 2009 to 2017 she served as the Director for the Centre for Children’s Literature and Culture in St. Patrick’s College and then in Dublin City University when the universities merged. From 2017 to 2019 she is visiting professor in John Paul Catholic University, San Diego, California. She publishes and lectures on Irish literature and the visual arts, women’s writing, illustrated children’s books, and short fiction. She published The Irish Scene in Somerville and Ross in 2007 and co-edited The Ghost Story from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century in 2010. Somerville Press published her latest book, Two Irish Girls in Bohemia: The Drawings and Writings of E. Œ. Somerville and Martin Ross, in 2017.

Have you a suggestion for our blog? Send an email to Dr Deirdre Flynn

Check out our guidelines for submitting blogposts here.