With Hannah Lynch in Tinos

Iliana Theodoropoulou

“here is at last forgetfulness of sorrow and unrest”[1]

- Tinos

Hannah Lynch visited Greece twice in her relatively short life. Her Greek island was Tinos. Her first journey there was a long stay of two years, from September (probably) 1885 to September 1887. Her second visit was shorter: six weeks from late March to the beginning of May 1902. In 1885 she travelled from Liverpool to Syros on board the “SS Roumelia” with the Papayianni lines.[2] From Syros Hannah crossed by a smaller boat and reached Tinos. Details of her sea journey are included in her novel Rosni Harvey.[3] Her first letter from the island is dated October 1885,[4] but there are indications in the archive of the Ursuline convent at which she stayed in Loutra, that she had arrived in early September.[5]

Lynch would later publish two articles about Tinos, and two novels in which the island is a central setting. The articles were written while she was living and working at the convent, and both were published in the Irish Monthly in 1886.[6] The novels are Rosni Harvey and her “Greek” work of fiction Daughters of Men, originally published only in English but later translated into Greek by Dimitrios Vikelas. Both were published in London in 1892. Her association with the convent is discussed in a previous blog article here.

In the first of her two articles about her experiences on Tinos, “November in a Greek Island”, she sets the scene of her sojourn in the convent by describing an early December morning in 1885 in which she sits in a small house in the garden of the Ursuline Convent writing. There, she enjoys the good, mild winter weather and occasionally picks an orange from the tree nearby to eat. In articles such as this, it seems possible that she used her time in the convent as a form of writer’s retreat, although we don’t know what she was writing. Her work could have included letters, articles, or a novel, but without doubt in her texts she captured the genius loci of the island in an unparalleled way.

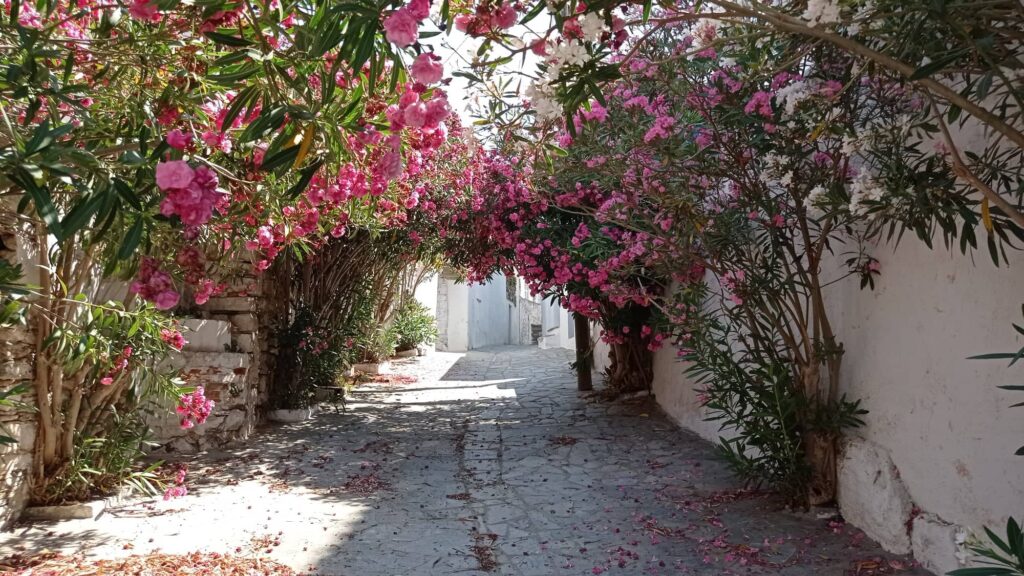

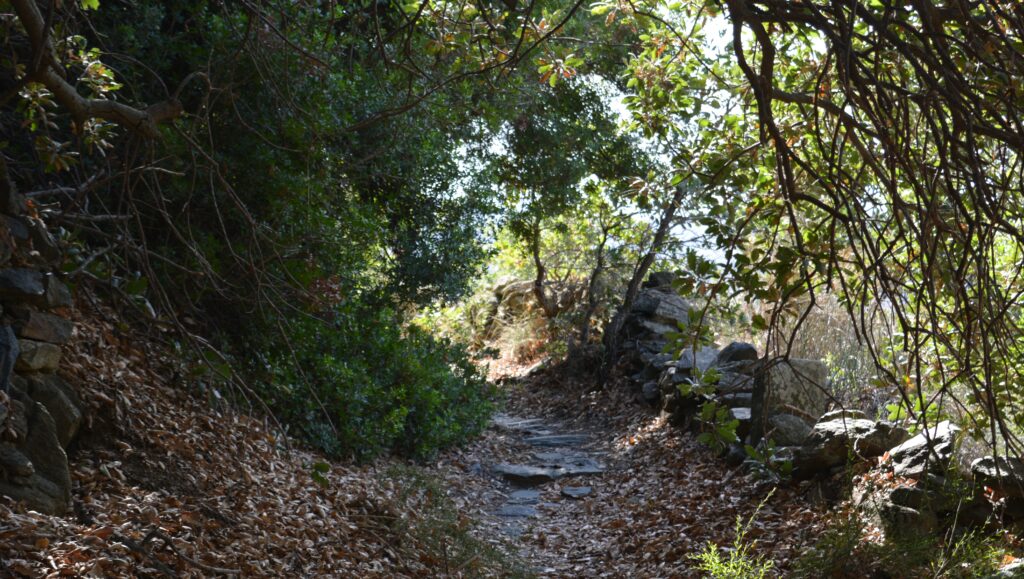

Having translated her essay “The Ursulines of Tenos” into Greek, and planning to translate more of her texts, I wished to get to know at first-hand the places she visited, the paths she walked. We become acquainted with a writer in a deeper way when we can visit the places they lived, enjoyed, and drew inspiration from and, in this case, wrote extensively about. However, walking in her footsteps has proven difficult if not actually impossible. Tinos has changed extensively over the last 50 years. In Lynch’s time, travelling on the island was possible only on foot or by mule or donkey, but now in the twenty-first century the old paths are quite forgotten and there is a new and more modern road network. With these changes, notions of close or far have changed. By bus, by car or on foot I tried to see Tinos through her eyes… to catch a glimpse of her, reflecting the landscape in her texts, and thus herself reflected in her own descriptions.

The Hannah Lynch who came to Tinos was in a state of permanent transition, in perpetual movement (motion): she climbed marble ledges, entered green torrents (as she described the vegetation that flourished along river valleys), found woods and secret waterfalls on a bare and dry island, and flowers with names unknown. Finding the places Lynch visited was not so much a problem: Loutra, Xinara, Volax, Ysternia, Pyrgos and all the other locations are still there. Exombourgo, the Venetian fortress overlooking the island, remains, too. The greatest difficulty was Hannah herself, who always seemed just ahead of me and I could never meet her…

From the text to the landscapes, with my camera, and back to the text, new details, new aspects always surprised me. She was a writer of passage and change, of people moving, of light changing, the sun rising or setting…a perpetual metamorphosis. This transition, this in between space, usually considered as a loss of time, a journey on board or on mule, was for her a precious space where a person becomes aware of a deeper self.

That particular December in 1885, Hannah Lynch was 26 years old, a young ambitious novelist, full of dreams, spending months of happiness and freedom on a Greek island. She is reachable and fully present in her texts during that first visit, delighted to embrace with her gaze the Aegean landscape, to climb every rock, every hill to enjoy the views, to combine the rhythm of her thoughts to that of her feet, eyes, nose and ears, and invite us, her readers, to walk with her and follow her footsteps. She is present in every detailed description, every subtle change in the sound and visual landscape of the island. She was accomplished at depicting nature in her later fiction set in Greece, as her friend, protector and translator Dimitrios Vikelas highlighted in his review of her Daughters of Men:

“Miss Lynch excelle dans l’ art de peindre le paysage grec. Elle a sur sa palette les nuances les plus variées et les plus délicates et elle en fait le meilleur usage”.[7]

2. Looking far away

In her novel Rosni Harvey, Lynch portrays a moment of seeing Greece for the first time:

Greece lay upon the sea splendidly coloured by the gathering tints in the east. The sky was pale blue, just touched with rose clouds, and above the mainland lay a bank of violet, dashed with gray and gold. On the other side rose Cerigo in purple-gray hillside, yellow stone, and hazy shadows upon a mauve-tinted sea. In the east the sky was crimson and orange, fading as the stars blew out their lights. Mount Elias, not now snowy, was a cold outline touching the hills of Marathonis a soft mass upon the horizon, the mauve and silver-tinted waters breaking from their dusky base. (Rosni Harvey p.218, Vol. 2).[8]

As the sun rises, a new world for Rosni emerges, a revelation of light and limpidity. Coming from the north-west of Europe it is no surprise that Hannah Lynch was impressed by the transparency and intensity of the Aegean light and wished to portray it. Like a painter she does not hesitate to use amply all the colours of her palette.

The Greek islands seen from the sea are untiringly unspeakably beautiful. Shadow and shine, delicate hues and strong ones melt into an inextricable haze, as do the sensations of the spectator incapable of analysis as he watches them. […. ] Here at last is forgetfulness of sorrow and unrest. (Daughters of Men p.128)

Such sights awed her, her breath is held, every time she sees the silhouette of the Greek islands at the horizon. Climbing on high rocks or from the sea, the view of the islands “start up in the scene like so many Jack-in-the-boxes”. (Rosni Harvey, p. 229, Vol.2)

Approaching Tinos by boat

Like a roseate jewel in a circle of sapphire, with opal and mauve and purple lights struck from it by the sun’s rays, lies Tenos upon the deep and variable bosom of the Aegean waters. (Daughters of Men p. 128)

I have been crossing the Aegean all my life, and again and again I am astonished by the beauty and uniqueness of it. Winter or summer, on quiet or windy or stormy days, being on this sea and looking at the silhouettes of the islands is just as she writes: a sensation that resists description and analysis.

View from Castro

you will see the dreamy Mediterranean, responsive to the slightest emotions of the Eastern sky, and you will be surrounded by soft, blue touches of land breaking above its white town half hidden by the cloud -shadowed hills, Syphona, a misty margin of gray upon the clear horizon, ancient Delos so dim as to appear neither wholly sky nor land; desert Delos, with darker, fuller curves of land upon a silver edge of water, and nearest Myconos, a blending of the purest blues, with the famous Naxos behind, washing which, whatever its mood in general, the Mediterranean is sure to take its own distinctive colour -sapphire. (“The Ursulines of Tenos”, p. 272)

This is a view from Castro, the rock where the Venetian fortress was situated. Syros, Myconos and Delos are near but Naxos and Sifnos are further away and cannot be distinguished clearly in the summer months. I have climbed up there in the end of September, planning to take photos, but I did not see this image…

3. Mixing colours, sounds, stones and flowers

Like a watercolour painter she mixes blues and mauves and water and creates this misty haze, delicate hues and washes.

Azure and sapphire: these are the two shades of blue she observes in the sea and the sky.

It is needless to speak of the colour of the Mediterranean or the Grecian skies. We are in the winter now, and except under the transient influence of rain I have not seen either, other than the proverbial sapphire tint, unless when the hours grow cooler, and then the intense depth of sapphire changes to the softest azure. (“November in a Greek Island”, p.377)

Mauve, Violet and Rose

The loveliest are the cyclamen, which I think may be appropriately called the eyes of the mountain here, as the thyme may be called their scent. One meets them everywhere in varying shades, from the faintest mauve to a violet bordering centrewards on rose. (“November in a Greek Island”, p.378)

Earth colours – the marble quarries near Ysternia

Looking at them carefully I grew to understand why the colour of the hills was so much mauve and golden mixed with the white. Where the marble has been cut or broken it takes the peculiar golden tint; where it remains intact time blends the white mauve, and both produce the wonderful effects of curve and shadow and luminous light that makes those Grecian hills an everlasting and nameless wonder. (“November in a Greek Island”, p.383)

Botany – The Ursulines, as if each flower was for each one of the thirty nuns of the convent

On the first of December I gathered a monster-bouquet, composed of tea roses, double and single geraniums of every colour, carnations, lavender, rosemary, marguerites, heliotrope, verbena, mignonette, snapdragon, bachelor’s buttons, maiden-hair, and the three first violets that have appeared. (“November in a Greek Island”, p.381)

Geology: the rock

The Castro- an appalling purple grey rock was partly hidden by the opaline white fog that lay upon it like a thick bridal veil wedding it to the sky, and through this haze the points of the rock were unevenly visible. But one could see it rapidly melting under the bars of gold that the sun shot down upon it, marveling, doubtless, that his royal message of light and clearness should so long have been resisted by this melancholy fortress, held in its gloomy memories of far-off days of pride and glory and Venetian splendour and importance.(“November in a Greek Island”, p.379)

Silence

High up upon a marble ledge, overlooking the breathless awful stillness of Bolax Valley, the air blew across from the furthest mountains with a stronger touch of sea-breeze through its own purity.(“November in a Greek Island”, p.377)

Oh, the stillness, the soft yet sharp enchantment of a night-watch upon the Aegean island! The distant murmur of the restless sea breaks the silence of the land, and the shadowy hills fall into the dense veil of the valleys. The charm enters the soul like a pang, and it works upon the quickened senses with the subtle mingling of exasperation, of poignant and tranquil feelings. (“Daughters of Men” pp.174-175)

Villages

Hannah Lynch lived in Loutra in the Ursuline Convent. Loutra was a village she clearly disliked (villainous, dirty) and is situated in Kato Meria (Lower Part). Tinos is divided in three regions, Exo Meria (Outer Part), Ano Meria (Upper Part) and Kato Meria: the Lower Part is where the catholic villages are located. She traveled extensively around the island and many villages are mentioned in her texts, mainly Loutra, Xinara, Bolax, Tinos Town but also Ysternia, Lazaro, Mousoulou (now Myrsini) and Pyrgos, the marble village in the north.

4. Where is Hannah Lynch? Flying like a butterfly

I suspect the charm lies in the wing and in the movement -both! Our natural desire is to mount, and these flying things appear to me the happiest, most enviable. But, unlike your wish to catch the luminous-winged thing, I prefer to watch it, and feel myself a part of it. The scents and sounds and sights that fill the air leave wishes in me impossible. Fix your eyes on the fly in an impersonal way, and you gradually find yourself growing like it, a tremulous sensibility, like it, unweighted with needs and desires. It must be a wonderful thing to know oneself really unchained, like the birds and the flowers; free to gush through life like this little stream, irresponsibly, unmeditatively; to only breathe and gaze and climb, like that long eared goat; to find all one’s joys in impersonal objects, like the sky, the earth, the air, without the vacillating impulses, desires and hopes of humanity. (Rosni Harvey, p.32, Vol 3 )

This paragraph from Rosni Harvey embodies all the travelling, longing, awe, and desire that emerges from her descriptions. Rosni expresses a desire to merge with the landscape, feeling like a butterfly herself, a “luminous sensitivity”. Carl Gustav Carus’ descriptions give a glimpse of what Lynch is exploring: “Climb to the topmost mountain peak, gaze out across long chains of hills, and observe the rivers in their courses and all the magnificence that offers itself to your eye – what feeling takes hold of you? There is a silent reverence in you, you lose yourself in infinite space”.[9] Her depictions of Greece capture a desire to expand herself and achieve an intimate correspondence between her inner and outer landscape.

This blog article is only a small anthology of her magnificent texts on Greece and aims to invite the reader to read her books and articles. I would like to mention here, too, that her passionate love for nature is captured in earlier articles published before her trip to Greece and of course later in all her travel writing. She writes, for example: “From my earliest years I loved the idea of new scenes and eagerly sought them”. (“A Glimpse of Southern Ireland in the Winter”, p.365).[10] She continued exploring new landscapes, new impressions, sounds, views and experiences until the end.

And above towered the Castro, slanting down from the upper world, greyer, sterner than ever, with the rocky desert of Bolax behind, and the villages afar, so white and tiny, tangled upon the slopes, curve flowing after curve to the horizon, the cornfields and meadows touching the scene to life, and the sea breaking into the wide green plain of Kolymvithra like a lake. (“Daughters of Men”, p.364)

[1] Daughters of Men: a novel by Hannah Lynch (London: William Heinemann, 1892), p. 128.

[2] According to the guide by John Murray, steamers by the Papayianni lines connected Liverpool to Greece three times a month, see: Handbook for Travellers in Greece, 5th edition (London: John Murray, 1884).

[3] Hannah Lynch, Rosni Harvey: a novel, 3 vols (London Chapman and Hall, 1892).

[4] She describes her adventurous travel from Liverpool to Syros in her first letter to Father Thomas Dawson, see: Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing, Hannah Lynch Irish writer, cosmopolitan New Woman. (Cork: Cork University Press, 2019), pp.16-17.

[5] Correspondence of the Superior of the Ursuline Convent of the Sacred Heart in Loutra Tinos, with Pierre Carteron, the French Consul of Syros, Archive of the Catholic Archdiocese of Tinos.

[6] Hannah Lynch, “The Ursulines of Tenos”, Irish Monthly, vol 14, May 1886 and “November in a Greek Island”, Irish Monthly, vol 14, July 1886.

[7] Dimitrios Vikelas, “Daughters of Men, a novel by Hannah Lynch”, La Nouvelle Revue, tome 77, Juillet – Août, 1892, Paris pp. 442-443.

[8] William Cochran traveled the same route a few months before Lynch, and published a very detailed account of this journey, illustrated with his own sketches. See William Cochran Pen and Pencil in Asia Minor, or notes from the Levant, London:1887.

[9] Carl Gustav Carus, “Letter II”, reprinted in “Nine Letters on landscape painting written in the years 1815-1824 with a letter from Goethe by way of introduction”, intro Oskar Bätschmann, translated by David Britt (Los Angeles, Getty research institute 2002), p. 85.

[10] Hannah Lynch, “A Glimpse of Southern Ireland in the Winter”, Shamrock Magazine, 10 March 1883. For a further discussion of her publications in the Shamrock Magazine see Kathryn Laing ed., Hannah Lynch’s Irish Girl Rebels: “A Girl Revolutionist” and “Marjory Maurice”, Edward Everett Root Publishers, Brighton 2022. See also Hannah Lynch, ‘Nature’s Constancy in Variety” Irish Monthly, vol 11, August 1883.

Iliana Theodoropoulou: I am a visual artist from Athens, Greece. I studied Surveying Engineering in Athens and Photogrammetry in London. I spent several years doing research and working in Berlin. Since my return to Greece, I have been exclusively working as a visual artist. My main field is painting, where my work inhabits the border between abstraction and landscape painting, but I also explore the possibilities of photography and film. I have had three solo exhibitions and participated in several group shows.