Emerging Voices 6: Éadaoin Regan

Éadaoin Regan is currently in the final year of her PhD in the School of English and Digital Humanities, University College Cork. Her thesis, A method to the madness?: Representations of psychological disorder in Irish women’s fiction 1870-1914, employs feminist psychoanalysis and postcolonial theory in its analysis of representations of mental illness in Irish New Woman fiction by Charlotte Riddell, Sarah Grand, George Egerton, Somerville and Ross, B. M. Croker and Clotilde Graves. Prior to her postgraduate research, she was awarded an MA in Literature from Ulster University (2015) and a BA (Hons) in English and History from UCC (2012).

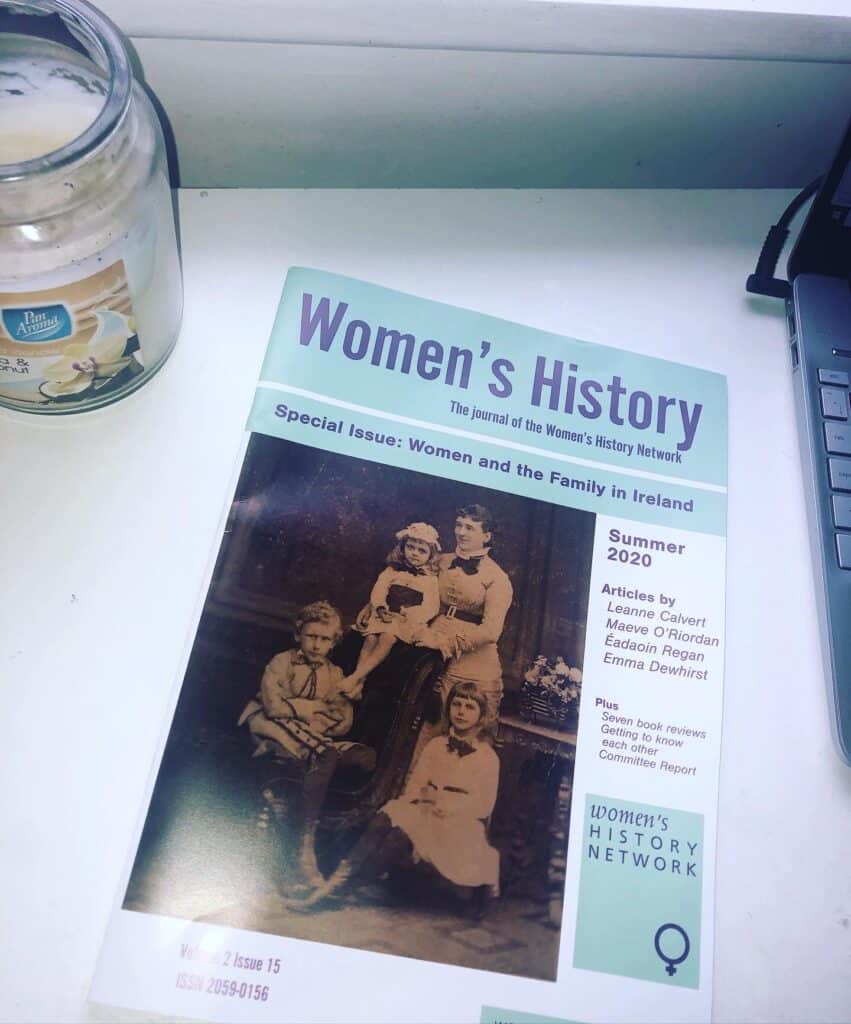

In 2019, Éadaoin was the recipient of the CACSSS Travel Bursary which facilitated her attendance at a symposium on Women and the Family in Ireland at the University of Hertfordshire. This led to her first publication, ‘“There’s [al]most always a cause”, madness and/or a mother complex: a Jungian reading of selected George Egerton stories’, which was published in Women’s History: The Journal of the Women’s History Network in 2020. She has been a First-Year Tutor in the Department of English at UCC since 2017 and has supported research development as Senior Tutor in the UCC Skills Centre since 2019.

On 26 July of this year, she will take part in the Irish Women’s Writing Network roundtable (‘Exploiting Intersectionality: Irish Women Writers in London, 1880-1940’) at the International Association for the Study of Irish Literature (IASIL) Conference, University of Limerick.

You can follow Éadaoin on Twitter at @ERegan91.

This is the sixth interview in the emerging voices series which aims to showcase and promote the work of current doctoral students and/or early career researchers who are working in the field of Irish women’s writing in the period between 1880 and 1920.

Q: Tell us a little about your research journey. Where and how were you first introduced to Irish New Woman writers and what about their work sparked your curiosity to pursue a PhD?

ER: My interest, and even awareness, of New Woman writers came quite late for me. I had taken a few years away from academia after my undergrad studies, and my MA did not explore any Irish New Woman writers. I had returned to education out of curiosity which means I did not have the passion I now have for going off course. Towards the end of my MA, however, I finally realised that I wanted to pursue a career in research. While applying for doctoral places, I also started carrying out independent research to explore what potential was there. During a supervisory meeting, my then-supervisor Professor Jan Jedrzejewski discussed a list of proposed texts for my doctoral research, and he suggested I revise my list of primary sources because the writers I had selected were already quite well-known (a rookie mistake!). When I asked if he had ever heard of any Irish women writers not already on the list, there was an “a-ha!” moment.

With huge thanks to the work that had already been carried out in the area, I was able to sort through and narrow down a list of potential authors from upwards of two-hundred Irish women published during the Victorian period. It genuinely floored me that there were so many, and the idea that these texts were not being studied from secondary school and upwards in Ireland seemed to me incomprehensible when the education system in Ireland was already placing a huge emphasis on Victorian and Irish texts. When I began to read the writers, my interest was further reinforced given the invaluable insight they provide into the minds, lives, and everyday struggles of contemporary Irish women – whether living in Ireland or not. We tend to see history through a lens which removes individuality, but these writers demonstrate that Irish women and their views were not straightforward in the way we often assume: i.e., nationalist or unionist, feminist or anti-feminist, pro-marriage or anti-monogamy. There is a complexity there that is often overlooked, just as there is a complexity to all these issues today. Even in the short few Irish New Woman writers I was able to include in my doctoral research, there are some significant deviations in their reactions to and representations of their world. It is endlessly fascinating.

Q: In your doctoral work, you explore perceptions of women and madness in fiction. In what ways does this study open up new understandings of Irish women’s literary production?

ER: It examines the extent to which selected female protagonists are aware of the contributory factors in their mental health and explores their agency in communicating their experience, and the consequences when they do not. This may seem an obvious contention today but many of these stories were written at or near the same time that theories of psychoanalysis were being developed. The idea that women were actively aware of, and responding to, inaccuracies about women’s insights into their own minds before psychoanalysis officially emerged is hugely important to understanding women of this era. Despite their prominence in the period they were actively writing, many of these women have remained critically neglected because they do not neatly encapsulate or focus on the Ireland envisioned and produced in the works of the Irish Literary Revival, a movement that remains disproportionately favoured by academics. Similarly, their work was often dismissed for not being set in Ireland, and thus viewed as not ‘authentically’ Irish.

Éadaoin Regan as a Plenary Speaker, UCC Bookends Postgraduate Conference, School of English and Digital Humanities, North Wing Council Room, UCC Campus, 14th April 2022.

The Irish women writers I have explored in my research often had widely varying views on issues like the Irish Question and women’s autonomy within and outside of the home. While their fiction is not necessarily autobiographical, of course there are instances where authorial opinion on society and culture is prominent in the text. Yet these writers also demonstrate that their interests were not sequestered to, for example, nationalism or maternal rights: they were interested in the idea of the individual, just as their male counterparts were. The varying needs of each individual are explored in my research, and these works portray the diversity of female experiences. There are characters who crave monogamy, those who don’t; those who want to be mothers but only in a way that is not dictated or controlled by their husbands or the legal system; those who succumb to society’s expectations to seek psychiatric help only to realise that it is society itself which is making them ill. And a psychiatrist, of course, embodies these same values. These are expertly crafted and intricate texts which play with modes of narrative and draw upon gothic, realist, or fairy tale motifs. They’ve often been criticised for not falling neatly into any genre, but for me that is their strength. They are distinctly of their time, as are the characters, whose complexity and depth make them very human. It is very important that we understand these intricacies.

Q: Several of the writers on which you focus in your research (Riddell, Croker, Egerton) were well known during their lifetimes but were subsequently obscured from Irish literary history. Why do you feel they merit reconsideration now?

ER: The neglect of Irish women in the historical and literary narrative of Ireland is evidenced most notably in the necessity for a dedicated rediscovery of Irish women’s lives in pre- and post-independence Ireland over the last forty years. While the characters I examine are fictional, the scenarios depicted, and the colonial and gendered culture Irish women had to contend with, are rooted in historical reality. Revisiting these texts provides us with an unprecedented and invaluable insight into Irish women’s lives.

These fin de siècle texts harbour unlimited potential for the comprehension of Irish women’s place in the narrative history of Ireland. During this period, Irish women were not only contending with the obstacles of domestic, social, and legal limitations but often the ‘Other’-ing that came with the British Empire’s handling of Ireland, as well. Fiction adds another dimension to our understanding of the struggles women experienced in the colonial environment. The debates are multiplicitous because of course not every Irish woman in this historical era would have considered themselves to be colonised, and even those who did may have been supportive of the British Empire’s expansion. Within the scope of my own project, this contrast is evident: George Egerton considered herself “intensely Irish”, while Sarah Grand was very much pro-Empire. Understanding the representations of women’s mental health issues in this complicated context is an important step to take in understanding the impact political issues had on women.

Q: Riddell, Graves and Croker were particularly adept at writing stories about spectral presences and hauntings. Is/was Irish female identity a distinctly troubled/troubling space?

ER: Absolutely. When I look back on the accounts – both fictional and actual – that I have come across in the past few years I recognise that Irish female identity is shown to be troubling on two fronts. The first is related to their Irishness: given that the justification for colonisation was to civilise the uncivilised, there was a prevailing effort by the British Empire to feminise or infantilise the Irish people during this period. Simultaneously, at the height of these colonisation efforts (roughly between 1870 and 1914), women’s rights movements were emerging in Britain and were met with much derision because the nation could not afford civil unrest at a time when it was outwardly portraying itself as a model of civility. There was a considered effort, therefore, to reinforce gendered ideals in a way which ensured women were limited to the domestic space. For Irish women this was particularly disastrous because it meant that they were battling stereotypes about their mental health and capacity to rule themselves on two fronts: first as women, then as Irish.

These issues of identity and their link to mental illness are prevalent in every text I explore in my thesis. There are many different manifestations of madness in these works, and various aspects of society or culture which contribute to these neurotic symptoms. But in each case, it is society’s interference with the female protagonist’s ability to realise their own identity that instigates madness. We all know the saying, “you cannot heal in the same environment that made you sick”, but what if that environment is so ingrained in your psyche that you can never escape it? This inescapability of identity is portrayed in the works of Croker, Riddell, Graves, and even Egerton. Whether it is religion, maternity, or that paradigm I’ve always found particularly eerie – the ‘Angel in the House’ – the spectre of the imposition of unnatural identities haunts these works. Coventry Patmore’s imagery of the angelic female presence moving through the house (barely seen and almost never heard) is ghostly in and of itself. Even in the stories which are not necessarily gothic, women are haunted/haunting presences.

For example, according to psychoanalysis a woman may become hysterical due to repressed sexuality. But what, then, do we make of a woman who is aware of her sexuality? We must then see it as suppressed rather than repressed. Otherwise, why would a woman in her right mind consciously stifle a desire, especially if she knows that doing so will make her unwell? In Egerton’s ‘A Cross Line’ from the 1893 Keynotes collection, the main character is a married woman who wants the freedom to explore a sexual relationship with another man. Given the era in which she lives and the fact she is pregnant, however, she must suppress these desires. As a result, hysterical symptoms occur. The negation of sexual freedom for women (but not for men) therefore can be seen as the cause of madness, not female sexuality itself. Her pregnancy is likewise not the cause of her hysterical symptoms but instead acts as a physical reminder that she now carries (both literally and figuratively) the responsibility to forever confine herself to one identity: that of mother.

The texts I explore always seem to come back to the same conclusion: that society, its structures, its stereotypes, and its restrictions on Irish women are responsible for women’s failing mental health. It is women’s unwillingness to act out for fear of being accused of being hysterical which causes symptoms to manifest. This consistent awareness in these characters of how they are likely to be perceived and the dangers associated with these perceptions, such as losing custody of children or being confined to an institution, preoccupies these works.

Q: Can you give us some examples of the types of psychological conditions that are represented in these texts?

ER: I had to really experiment with how my research was going to be organised because of the wealth of material which depicts psychological conditions. I eventually narrowed it down to four broader categories within which I could then specify psychological conditions, explore their cultural or colonial impact, and examine the extent to which they suggest women’s awareness of their mental illnesses. These categories are sexuality, maternity, individuality, and hauntings as projections of mental illness. I can briefly outline one psychological condition which draws a connection to some of the ideas I’ve already discussed.

The link between maternity and mental illness in fiction is often assumed to be postnatal depression, regardless of the age of the child. However, by using Carl Jung’s mother complexes and Karen Horney’s culture complexes as frameworks for analysis I was able to provide a more specific and culturally grounded explanation for the symptoms depicted in these works. For example, Carl Jung’s mother complex is one which stems from his theories on archetypes, specifically his contention that the idea of the Great Mother is collectively inherited: it is a trope or character whose traits (all-knowingness and nurturing) are recognisable to almost everyone, regardless of background, religion, or beliefs. An additional aspect of the mother complex is the nothing-but-daughter element. According to Jung, the nothing-but-daughter occurs when a daughter’s identity is so closely tied to and informed by the mother that they cannot possibly have an identity of their own. Jung believes this is a positive complex but I take issue with his findings. I argue that, in an Irish context, the nothing-but-daughter is a negative manifestation of identity given the cultural environment and society’s misunderstanding of its psychological impact. In the texts I explore in my thesis, the impact of this complex on the protagonist always proves fatal.

In Egerton’s ‘Oony’, from Symphonies (1897), for instance, the titular character is born of a mixed Protestant-Catholic marriage which, in rural Ireland, means Oony inherits the stigma of her pregnant mother, who is murdered at the beginning of the story. This stigma impacts Oony’s ability to live peacefully in a house with Catholics who are cruel to her due to her Protestant background, to forge friendships in a village which fails to recognise that her thin figure is a symptom of abuse and poor mental health rather than a sign that she is a changeling, and finally to marry the suitor who refuses to consider her as a potential wife due to the combination of these factors. Jung’s theory is a helpful framework through which to trace Oony’s need to inherit her mother’s identity by becoming a mother in her own right. In a society which does not facilitate her search for a family of her own, she becomes her mother in a sinister way. Understanding the Irish context is central to carrying out a successful psychoanalytic reading of this text as the rural Irish, specifically lower-middle class, culture explains many of society’s mishandlings and misperceptions of Oony which lead to the story’s tragic end. I don’t want to spoil the story here, but for those interested in knowing more I have published an article on the Jungian complexes in Egerton’s work in Women’s History: The Journal of the Women’s History Network in their Special Issue: Women and the Family in Ireland (Summer 2020).

Q: Which of the writers you are researching do you deem to be the most challenging in their depiction of mental illness, and why?

ER: In an era of mass interest in true crime I am not easily troubled. But I found Egerton’s ‘Wedlock’ from Discords (1894) particularly difficult, not due to any research or methodology problems but because it is a genuinely disturbing story. To preface, there are many psychological symptoms the protagonist, Susan, displays that can be categorised as stemming from alcoholism and postnatal depression. However, I think it is one of Egerton’s most impactful pieces of work because the third-person narrator allows us to see not only men’s perspectives of Susan, but also affords us insight into the views of a woman writer who is a boarder in Susan’s toxic household. In the story, Susan’s husband deprives her of access to her biological daughter and forces her to stepmother his three children. The writer character sees all and hears all, yet though she gradually becomes more sympathetic to Susan, she does not have any influence to change Susan’s situation. It was one of the most challenging texts to discuss in my thesis because while all the protagonists are complex women, Susan is particularly so. While you are sympathetic to her, at times Susan’s violent actions make you understand society’s criticisms. However, ultimately, through the course of exploring the text any opportunity for Susan to be good is compromised by a patriarchal figure or patriarchal society itself.

I would advise anyone interested in complex opinions on maternity during this era to read it, but with a forewarning: it does contain an act of filicide. It is very much intended to shock, I think, but with the purpose of highlighting the horror and mental health impact of society’s interference with a woman’s mothering, a role that patriarchal society insists women are made for but then does not trust them to undertake.

Q: At times, literary texts lose their critical currency because they respond to a particular historical moment and its concerns, and over time those issues cease to captivate or resonate with readers. What, in particular, struck you about these women’s representations of madness and do they speak to contemporary anxieties or obsessions?

ER: I think what struck me the most is how much of what these writers discuss in their fiction is still relevant today. Society, culture, technology, and opportunities have, of course, evolved since these texts were written, but a lot of the perceptions of and expectations placed upon women have not. I understand that this might seem rich coming from someone using psychoanalysis in their methodology, but these Irish women writers and many before the remit of my project were already actively responding to stereotypes of women in various ways including pseudonymous and non-fiction writings, rallies, marches and in plays long before the development of psychoanalysis as a theoretical discipline. The gendered perception of women as biologically destined to be mad at some point in their lives is still very much part of everyday conversation. It was and is convenient for aspects of society, especially those corners of it in which patriarchal beliefs are entrenched, to shirk responsibility and play the “women are mad” card. We see it all the time.

Take for example celebrity culture. A woman acts a certain way and she is vilified in the media for being a shrew. A man does the same, he is labelled innovative and his actions are described as a demonstration of passion or creative genius. We see these same types of issues in the societal scandals of the nineteenth century, but the fact that these stereotypes continue to exist and even proliferate is telling. And that’s only discussing the modern parallels at surface level. If we look to what is happening in the United States now and the threat to women’s autonomy that is occurring there, it is hard to believe we are living in 2022. If we look closer to home, the treatment of women seeking abortion in the whole of the island of Ireland is still a far cry from adequate, and the harassment of women seeking these services is appalling. The complexity amongst the people of Ireland is there also. In this scenario, too, we see women protesting against women. It is hard to ignore the parallels and hard to dispel a sense of disappointment that these issues are still a prominent but necessary topic of conversation.

It is the same for Irish identity. You only have to glance at Twitter to see discussions by Irish people who are aware of the struggles of nationalism and yet will dismiss those who have every right under the Good Friday Agreement to call themselves Irish. Similarly, we have a very culturally diverse Irish community now that should be celebrated, but again we see Irish people questioning the rights of certain Irish people. Racist attacks are increasing. Issues of national identity and women’s autonomy remain a huge concern, as are the variety of opinions and conflicts they instigate. The impact of everyday life on mental health is always going to be relevant to the reader, but the topics explored in these Irish women’s texts unfortunately continues to strike particularly close to home.

Q: Are these texts readily accessible and, if so, are there any novels or stories you would particularly recommend to readers?

ER: Thankfully, yes. Most of the texts I explore in my doctoral research are available on http://www.archive.org for free. I admit to being biased and would recommend every single text I have read, some of which did not make it into the thesis. However, I will begin by recommending Sarah Grand’s Ideala: A Study From Life (1888) and then taking note of the contrasts between that text and Egerton’s The Wheel of God (1898). Both deal with a woman’s search for an identity which feels authentic to her, society’s interference in and disruption of the realisation of that identity, and the mental health issues that result. Both are excellent novels which, I argue, insinuate that the only adequate cure for mental illness is complete separation from the society that causes their neuroses. Each also portrays very different representations of colonisation. However, Egerton’s text interestingly suggests that religious Ireland is not only a significant catalyst for her neuroses, but also haunts her search for an identity outside of Ireland.

In addition, while I can highly recommend any of Egerton’s short stories, her novella Rosa Amorosa: The Love-Letters of a Woman (1903) is a fascinating text. It is almost entirely written in letters between a woman, Rosa, and her lover, but we as readers are only privy to one side of the story. The book affords us an insight into the protagonist’s evolving mental state and plays into the idea of an unreliable narrator. As an accompanying read, I would suggest ‘The Man Who Could Manage Women’ in The Cost of Wings and Other Stories (1914) written by Richard Dehan (one of Clotilde Graves’ pseudonyms). This is the story of a wife’s decline into mental illness as a direct consequence of her husband’s treatment of her. It is told by a third-person narrator who provides the reader with an insight into society’s perception of the marriage and the husband’s secret feelings towards his wife. Unlike with Rosa Amorosa, we have no sense of the woman’s side of the story or her thoughts until the close of the text when, in a powerful scene, Dehan forces us to question our previous understandings of her protagonist’s mental health.

These suggestions are just the tip of the iceberg – I have so many more I could offer.

Q: On a very different note, we noticed that you and two colleagues at UCC launched an innovative podcast (PhD Pending) which explores a variety of topics related to the experiences of being a doctoral candidate. It launched just after the start of the pandemic lockdown. Can you tell us more about this project and your involvement in it?

ER: Yes! While travelling from Waterford to Galway to a conference in 2019, my future co-hosts Dr Anne Mahler, Dr Jennifer de Bie and I discussed the idea of launching a podcast, though not in detail or with any great sense of urgency. When the pandemic hit in March 2020, however, we were all working from home and our teaching had been cancelled for the rest of the semester, so we had a bit more free time on our hands. At this point, we all committed to producing one season, thinking we wouldn’t get much traction, but it would still be a nice moment for us to have; a time capsule of some sort. Within two weeks we had started recording and had our social media ready to go.

I drew up a rota to allocate our necessary administrative duties, and we decided to pre-record aan entire season over the course of two or three recording sessions. Then, based on a rota I had drawn up, we carried out social media, edited the podcast recordings, proof-listened, wrote up questions for new episodes, etc. It was a highly collaborative process. To our surprise, it very quickly spread to an international audience which meant we grew in confidence and began to plan more seasons in which to talk about a variety of aspects of PhD life. We also made sure to experiment with the sound equipment and editing software, as we had no budget but wanted to keep improving because we knew that people were actually listening!

PhD Pending Team Recording 2022: Top left: Dr Jennifer de Bie, UCC, Top right: Éadaoin Regan, and Bottom: Dr Anne Mahler, UCC PhD Pending Team: L-R: Dr Anne Mahler, Dr Jennifer de Bie, Éadaoin Regan

There are a huge number of podcasts on PhD life, but those that existed before ours catered almost exclusively to the sciences. The need for something like this existed, and by the end of our first season, we had been streamed in at least 27 countries. I stepped away from the podcast after season 3 to focus on other projects, as did Jenni, but I have recently returned as a regular co-host on the Patreon-exclusive series, PhD Pending: Coffee Break. This is a weekly catch-up where we chat about the everyday tasks that we worked through that week, struggles, any good news, breakthroughs, etc. It offers a more informal contrast to our main episodes. The idea is to offer the listener a sense that they are having a coffee with fellow PhDs discussing the everyday. I occasionally return as a guest to the main podcast, and I’ve recently recorded an episode for Season 7. As of today, the podcast has over 11,300 streams in approximately 40 countries, so we are all really proud of it, and especially proud of Anne for keeping it going.