Memory, Landscape and Loss in Irish Emigrant Women’s Memoirs

Dr Sarah O’Brien, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick

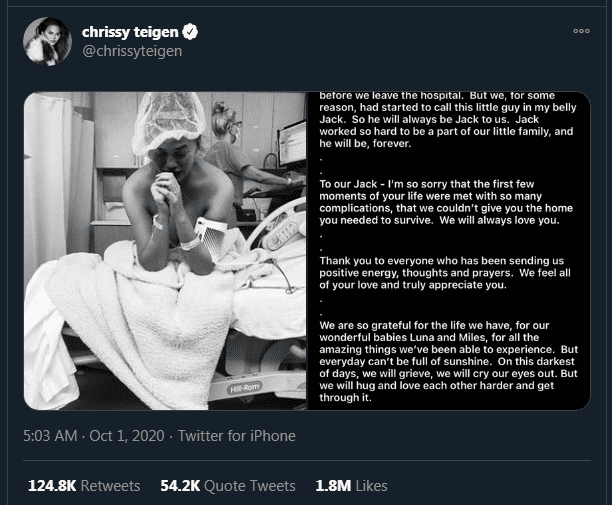

In October, a woman uploaded a photo to her social media account. Taken that morning, it showed her at the edge of a hospital bed, head held in her hands. Her body, partly exposed by a drooping towel, was doubled over in grief. She had just suffered, or was in the process of suffering, a miscarriage.

Behind her, a female medic stood at a computer monitor, facing away from the camera. Against the contorted shock on the face of the patient, the medic’s gaze seemed composed, mysteriously impassive. Clinical indifference was not in question here. Rather, what the image captured was the disorientating paradox of miscarriage: its devastation and its ubiquity.

Within hours of its publication, thousands of comments lined the photo. The woman at the heart of the image was a celebrity, Chrissy Teigen. Many of her followers wrote compassionately, praising her for so candidly sharing her loss. However, many, many more were outraged by the post. “This should be kept in the home,“ one young male wrote. “Don’t use your baby for clout,” wrote another. “The need to document everything for public consumption. Isn’t anything sacred?” asked a woman called Kristen. “Nowhere did I see [in my miscarriage] a photo opportunity” wrote another commentator. “Talk about it, great… but this look at me culture needs to stop.”

Up the road from where I live, in the West of Ireland, there is a green meadow dotted with lichen-covered rocks. Dock leaves, thistles and wildflowers abound, signaling that the local farmer has not allowed this place to be grazed. Some of the rocks are shaped into a semi-circle. Others are scattered more erratically, distinguished from the stony soil by the deliberate way that they’ve been pulled out of the earth. Many larger rocks have now collapsed but you can still see how some human force had once arranged them to point upwards, toward the sky. You can imagine, if you try, the flurry of hands that drew these rocks out of the earth, under a pale moon. Standing here, you can almost see the fingernails caked in mud and hear on the wind the whispers of a whereabouts.

Locally, this place is known as a cillín: an unofficial graveyard reserved for babies who died in childbirth, before the sacrament of baptism. From the mid sixteenth until the mid 1960s, and possibly beyond, cillíní were the places where unbaptized infants in Ireland were buried, often under cloak of darkness, without wake or funeral. These were places that were rarely visited and never discussed. Even today, no markers exist to register this place as a cillín. You have to learn to scour the landscape to look for them.

It is estimated that close to1500 cillíní are scattered across Ireland.

For the last five years, I’ve studied the autobiographies of Irish emigrant women. Initially, I was interested in the vernacular perspective that their writing could bring to the subject of Irish emigration. However, I’ve gradually become aware that the appeal of memoir for these women was not to recover a migrant journey. Rather, it was a legitimate genre to address a delegitimized subject. And consistently, this subject was miscarriage.

Sometimes, women positioned themselves as silent witnesses to these awful experiences. “Father took the little coffin to the cemetery in the buggy”, wrote Mary O’ Mahoney, using memoir to narrate the second infant death suffered by her West Cork-born mother. “Mother turned her face to the wall and cried. She always tried to hide her emotion from us children, but I knew how she felt. I went out in the kitchen and washed the dishes and I am afraid dropped my tears into the dishpan.”

In an essay about cillíní, Marion Dowd notes the sense of sin and guilt that was assumed by the bereaved mother.[i] Mothers were excluded from attending their child’s burial in the cillín because she was not yet “churched” — a purification ritual carried out by a priest in church. It was also believed that children who died before baptism would remain in limbo, never to be reconciled with their parents. “Many mothers died without ever knowing where precisely in a cillín their baby had been buried.” writes Dowd. “She was seen by many, including herself, as a failure.”

One emigrant memoir that I have failed to forget was written by a woman called Nora O’Connor. Nora was nineteen years old when she emigrated in 1906 from Bantry to New York City. Her memoir, written from Michigan in 1947, exceeds one hundred pages, each of which I’ve read, in awe, over and over again. Nora was an enormously evocative writer. Despite limited access to formal schooling (she was pulled out of school at fifteen to work as a servant) she had a talent for storytelling and self-expression that, in different circumstances, might have met a much wider audience.

Nora signed her manuscript as ‘Mom’ rather than with her name. Her memoir became a family heirloom, a rolled-up, paper-thin manuscript consigned to the recesses of the attic. Its last paragraph suggests, I think, the intent that drove Nora to complete this great literary effort. The passage begins with Nora’s description of the birth of her second daughter. “In June of 1916 a baby girl arrived”, Nora writers. “A baby with dark hair, lots of it, and big blue eyes:”

They didn’t tell me until the next day that she had been born with a ruptured spine … I suffered every pang with her and died a thousand deaths… She died on the 13th of September. Every baby I saw after I lost her, I wanted to hold in my arms, they seemed so empty. I missed the feel of her little head against my shoulder. Time heals all sorrows. But it’s hard to part with loved ones even as time goes by and tears are dried in the eye. They are still shed in one’s heart: that I know now so well.

It’s not difficult to imagine that there was something cathartic for Nora O’Connor in writing about the loss of her daughter, thirty-one years after her death. And yet, I am saddened by the great swathe of time that had to pass before she was able to fully express this maternal heartbreak. Also, I think a lot about the sheer accident of chance that led her memoir to be rediscovered, typed up and archived, in 1995, by an attentive family member. The probability that her memoir might have been lost, destroyed, or thrown out was so great. How many other women’s personal writing has met this fate?

Re-reading Nora O’Connor’s final words, I wonder if what most outraged people about Chrissy Teigen’s photo is its refusal to remain fixed to the limits of a highly-conventional genre. Her picture was not retrospective. We were not passing through this woman’s memory of her son’s death. Rather, we were direct witnesses to the event and thus dispossessed of the fictive framing and vast temporal distances that mediate most women’s narratives of miscarriage.

Also, and this seemed the clincher for many people, the photo was posted publicly, and possibly taken for a public audience. Unlike the flimsy manuscript of a memoir, there is no chance that this photograph will be lost, destroyed or forgotten. “Is anything sacred?” they said. “This should stay in the home,” they said. The insistence that a miscarriage remain a private business, treated in some cloud of dignified silence, hidden away in an attic, remains as steadfast as those gashes of rock scattered across the woods and fields and byways of Ireland.

Walking through the landscape, thinking about the millions of Irish women who left these shores, I often return to a single question. How did emigrant women remember, in the absence of place? In Ireland we are said to be afflicted with an inherited sense of topophilia. We seek answers, meaning and, above all, memories in the landscape. But then, standing in this cillín, I’m not sure that the Irish landscape has ever been so welcoming a canvas for women’s memories. This unmarked, dock-leaved field, this site from which women were systematically excluded, is testament to that.

Sarah O’Brien is a cultural historian in Mary Immaculate College, Limerick. Her work explores the Irish emigrant experience from the perspective of memory and gender. Prior to MIC she was an associate professor in Trinity College Dublin, the University of Buenos Aires and Northern New Mexico University, USA. She is the author of The Irish in Argentina (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), which explored the effects of the Argentine military dictatorship on the Irish-Argentine community. Her forthcoming monograph is under contract with Indiana University Press. It explores the memory patterns of Irish migrant women in the U.S. and England from the late nineteenth century.

Would you like to submit a blogpost? Check out our guidelines here or email Dr Deirdre Flynn.

[i] Dowd, M. ‘On cillíní.’ In Weir, T. Cillín. Royal Hibernian Academy (Dublin, 2019)