‘THE EXTINGUISHED CASTLE’: ELIZABETH BOWEN’S HAUNTED HOUSE IN ‘HER TABLE SPREAD’

Dr Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado (Queen’s University Belfast)

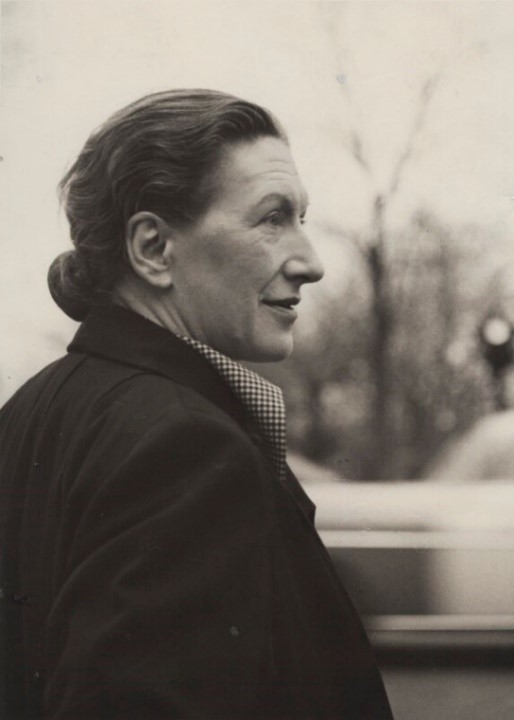

Elizabeth Bowen (7 June 1899 – 22 February 1973)

Fig. 1 Elizabeth Bowen by Elliott Erwitt, 1950. National Portrait Gallery.

Elizabeth Bowen had a thing for haunted houses. They appear frequently in her oeuvre, and especially in her short stories. One such tale, the comically grotesque ‘Her Table Spread,’ from her fourth short story collection The Cat Jumps (1934), is set in a mysterious, unnamed ‘Castle,’ whose mistress hosts a dinner party which takes an extraordinarily strange turn.[i] Valeria Cuffe is an Anglo-Irish heiress in need of a husband and child to secure the future of her Castle and her line, and in this Gothic story Bowen explores the dark fantasy of Anglo-Irish ‘rule’. It is much-anthologised; for not only is it one of her best pieces of short fiction, it is also one of her handful of ‘Irish stories’. Of the eighty or so stories that Bowen published, less than a dozen are set in Ireland. Although the majority of critics have described ‘Her Table Spread’ as a haunted house tale, they have only discussed the spooky Castle in question as a generic symbol for the Anglo-Irish Big House. While the Castle does function on this level in the story, I would posit that its symbolism is far more layered and complex than critics have theorised previously.

‘A Conversation Piece’

Fig. 2 Bowen’s Court, Co. Cork, Ireland. Date unknown. Archiseek.com

Firstly, the timing of this story’s publication is highly significant: ‘Her Table Spread’ originally appeared as ‘A Conversation Piece’ in London’s Broadsheet Press on 4 May 1930.[ii] Elizabeth’s father Henry Bowen died that same month after a prolonged bout of mental and physical illness.[iii] When Elizabeth received word that her father was dying she returned from Oxford to her homeplace, Bowen’s Court in northern Co. Cork, to keep him company during the last few weeks of his life. Upon his death, Elizabeth became the new mistress of Bowen’s Court and the first woman to inherit the house since it was built by her ancestors in the 1770s. She observes of their country house, ‘With the end of each generation, the lives that submerged here were absorbed again. With each death, the air of the place had thickened. The dead do not need to visit Bowen’s Court rooms…because they already permeated them.’[iv] Bowen felt that houses are constructed of personalities, and they manifest in her writings as personifications of their inhabitants, both living and dead.

I would argue that the uncanniness of ‘Her Table Spread’ has its source in biographical detail. Bowen wrote the tale during her father’s decline, and the pressure of her impending inheritance weighed heavily on her as an only child and soon-to-be orphan.[v] Furthermore, Elizabeth had very little money, since as the ‘last issue’ of the Bowens she lived at her ‘own expense.’[vi] In early 1930 Bowen was a woman of thirty, married to an English civil servant, Alan Cameron, with whom she did not have any children. At this time, Elizabeth remained a virgin – their relationship was unconsummated and it is unclear whether this was due to Alan’s injuries sustained in the Great War, or whether he was gay.[vii] Her childlessness was likely a topic of much anxious ‘conversation’ among her family, hence the original title of the story.

Since Elizabeth was still a virgin in 1930, she did not feel herself to be a proper ‘adult’, and I would contend that Valeria Cuffe, the overgrown girl in ‘Her Table Spread,’ is a projection of the author’s id. The id is the disorganised part of the personality structure which contains basic human instinctual drives – particularly sexual and aggressive impulses – and it is the only component of personality that is present from birth. Bowen writes in The Death of the Heart (1938), ‘I swear that each of us keeps, battened down inside himself, a sort of lunatic giant – impossible socially, but full-scale – and that it’s the knockings and batterings we sometimes hear in each other that keeps our intercourse from utter banality.’[viii] Valeria is Bowen’s own ‘lunatic giant,’ and her convoluted romance plot in the tale reflects the author’s anxieties about her personal life.

‘Your Ancient Irish Castle’

Fig. 3 Kilbolane Castle, Co. Cork, Ireland. By Mike Searle.

When discussing Bowen’s Court with an acquaintance, Elizabeth revealed, ‘My father went mad here.’[ix] She had an abiding fear of going mad – the Bowens had an extensive history of madness, which was linked to their ‘obsession’ with property, ‘subjection to fantasy and infatuation with the idea of power.’[x] The Bowens believed their ‘power was mostly vested in property (property having been acquired by use or misuse of power in the first place).’[xi] Nevertheless, the Bowens endured significant financial losses throughout the centuries, shedding several properties that once belonged to the family: in Co. Cork, Kilbolane Castle, a ruined fifteenth- or sixteenth-century fortification (where Bowen’s ancestor John II was born), and Kilbolane House, a country estate which John II built in 1695; in Co. Tipperary, Ballymackey Castle (circa 1600) and the seventeenth-century house Camira, both of which Elizabeth’s father inherited and lost; and in Co. Dublin, 15 Herbert Place, the Georgian house in central Dublin where Elizabeth was born, which her father later sold.[xii] Elizabeth was the last direct descendant of the original ‘big Bowen,’ a Cromwellian colonel whom she dubs ‘Henry I’ in her account of the house, also named Bowen’s Court (1942).[xiii] In this book Bowen traces the successive ‘reigns’ of her ancestors in Ireland and, as Hermione Lee observes, she ‘distinguishes her family generations from each other as though they were monarchs.’[xiv] In a letter to Elizabeth, her friend Virginia Woolf called Bowen’s Court ‘your ancient Irish castle,’ and Bowen plays with this notion throughout her family history and within her fiction.[xv] When ‘Her Table Spread’ is read in light of these factors, it reveals itself to be a refraction of Bowen’s internal turmoil at the thought of inheriting Bowen’s Court. This psychodrama unfolds in the story’s otherworldly setting, an imaginary Castle that is heavily weighted with symbolic imagery. For the Castle in ‘Her Table Spread’ is a composite of Bowen’s Court and other Big Houses to which the author had a close family connection.

‘Not for Nothing’

The characters in ‘Her Table Spread’ live in splendid isolation (and dilapidation) in an ancient, fortress-like Castle which surveys the waterfront. Bowen’s protagonist Valeria Cuffe is an Anglo-Irish heiress of ‘twenty-five, of statuesque development, still detained in childhood.’[xvi] She is an orphaned only child, and her aunt worries that she will ‘die childless, in fact unwedded; the castle would have to be sold and where would they all be?’[xvii] Valeria looms large in the story, striding about with her ‘red satin dress cut low’ and her beaded bosom heaving with excitement at her special guest’s imminent arrival.[xviii] She thinks, ‘Not for nothing had she had the dining-room silver polished and all set out. She would pace around in red satin that swished behind.’[xix] Valeria envisions herself as the ‘princess’ of her crumbling Castle, awaiting a wealthy, gallant, preferably English paramour to secure her future.[xx] Cue Mr Alban – a hapless, preening, snobby Englishman whom Valeria invites to a lavish feast. The tale opens with a knowing wink: ‘Alban had few opinions on the subject of marriage; his attitude to women was negative, but in particular he was not attracted to Miss Cuffe.’[xxi] Bowen names him after Saint Alban, the first recorded British martyr, in an ironic allusion to the British history of propping up the Anglo-Irish, only to seemingly abandon them after the Union.[xxii]

Initially, ‘Her Table Spread’ has the veneer of a standard drawing-room comedy, with Alban playing the piano badly for the tone-deaf party of women. They include Valeria, her widowed aunt Mrs Treye, and her aunt’s friend Miss Carbin. Valeria’s drunkard great-uncle Mr Rossiter is to join them later. Alban intends to spend the night at the Castle and he becomes emboldened by the occasional attentions of the women, who shift their gaze intermittently between their guest and the window that ‘look[s] out over the estuary.’[xxiii] They are pleased to have a male visitor, and gradually he takes on their desired form: ‘Engulfed by their pleasure, from now on he disappeared personally.’[xxiv] Bowen sets up the tale as ‘a conversation piece’ in the sense of a painting that depicts figures arranged in a familiar scene. However, something quite literally dampens the mood of this tableau: the rain is ‘continuous,’ the Castle is dank, ‘the piano [is] damp.’[xxv] During Alban’s stay, a creeping condensation rises from the estuary below and enshrouds the chateau, lending a clammy closeness to the air. Such sexually metaphoric imagery of female arousal is evident throughout the story, which plays out Valeria’s deranged romantic fantasies.

‘A Smothered Island’

At the opening of the tale the narrator recounts, ‘The Castle was built on high ground, commanding the estuary; a steep hill, with trees, continued above it. On fine days the view was remarkable…with that constant reflection up from the water that even now prolonged the too-long day.’[xxvi] Despite its ‘beautifully remote’ environment, which has the apparent timelessness of a fairy story, there are specific geographical and historical details:

nearer the windows, a smothered island with the stump of a watch-tower. Where the Castle stood, a higher tower had answered the island’s. Later a keep, then wings, had been added: now the fine peaceful residence had French windows opening on to the terrace. Invasions from the water would henceforth be social, perhaps amorous. On the slope down from the terrace, trees began again; almost, but not quite concealing the destroyer. Alban, who knew nothing, had not yet looked down.[xxvii]

Although Bowen does not name the location, these topographical features convey a built history which places it in Ireland, and which references its contemporaneous moment, as well as its ancient past. Nonetheless, the sardonic narrator suggests that because he is English, Mr Alban ‘knows nothing’ of Irish history. Consequently, he does not know what he is in for by courting Miss Cuffe. The tale’s twilight setting reflects the waning power and influence of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy.

The destroyer anchored in the estuary is an incongruous element in this otherwise dreamlike vista. It jars the reader and it also confuses Alban, who is informed by Mr Rossiter, ‘By a term of the Treaty, English ships were permitted to anchor in these waters.’[xxviii] This clue indicates that the story is set in Ireland following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which ended the Irish War of Independence. The Treaty authorised the British Royal Navy to utilise designated Irish ports because the presence of ‘enemy’ ships was an enduring concern in the years after the Great War. Miss Carbin tells Alban, ‘That spring there had already been one destroyer’ in the estuary and the sailors visited the Castle, but ‘we were all away at Easter. Wasn’t it curious they should have come then? The sailors walked in the demesne but never touched the daffodils.’[xxix] At dinner they debate whether it is in fact ‘the same destroyer,’ and in their agitation the women wonder aloud, ‘“Will they remember?” Valeria’s bust was almost on the table.’[xxx] Miss Carbin affirms that the reappearance of a destroyer ‘is quite an event…These waters are very lonely; the steamers have given up since the bad times; there is hardly a pleasure boat.’[xxxi] The women have long daydreamed about the sailors’ return – especially one Mr Garrett. Valeria recalls, ‘Her friends had told her Mr Garrett was quite the Viking…She still had to remind him that the island was hers, too.’[xxxii] Here Bowen alludes to Ireland’s history of conflicts: the First World War, the Irish War of Independence (‘the bad times’), and much older clashes between the Irish and foreign ‘invaders’. The spectral presence of the destroyer in the tale symbolises the way in which twentieth-century Ireland is haunted by its violent past.

The Castle’s position overlooking an estuary is evocative of another great house that Bowen knew: the one where her mother Florence Colley was reared. The Colleys were an affluent, old Anglo-Irish family who lived in a grand Victorian gabled house built in 1863 called Mount Temple House in Clontarf, on the Malahide Road, a coastal route along Dublin Bay.[xxxiii] Clontarf is bordered by estuaries, and earlier maps show an inhabited islet called Clontarf Island off the coast, which was later submerged by a large storm (hence the ‘smothered island’ mentioned in the story). Elizabeth’s beloved parents Florence Colley and Henry Bowen were married in Clontarf; thus, the site has a deeply romantic association for the author. Like the Bowens, the Colleys were also obsessed with property – specifically, the lost family home at Castle Carbery in the townland of Carbury (Cairbre in Irish), Co. Kildare. As Victoria Glendinning comments, it ‘had long ago, needless to say, since this is an Irish story, fallen into ruin and become uninhabitable.’[xxxiv] Castle Carbery was a grand Tudor manor set atop Carbury Hill, which was also known as Fairy Hill. The Elizabethan Castle had ancient foundations; for the motte on the hill was built by an Anglo-Norman nobleman who was bestowed the area by Strongbow. Kildare experienced successive interethnic conflicts and the Carbury property changed hands several times. In 1588 it was granted to the Colley family, who built a large stronghouse in the seventeenth century. Although Castle Carbery was eventually abandoned, the Colleys continued to earn income from the surrounding land centuries later. Thus, Mount Temple House and Castle Carbery also haunt the Castle in ‘Her Table Spread.’ Bowen implicitly references the histories of their respective milieux in her tale, alluding to the Battle of Clontarf between the Irish and the Vikings for control of Dublin, as well as clashes between the Anglo-Normans and Gaels, and subsequently, the English and Irish, in Kildare. Therefore, the ‘smothered island’ in the story also symbolises Ireland, with its long history of foreign incursions and repeated attempts at possession of the isle.

Fig 4 Mount Temple House, Clontarf, Ireland, 2016. Image by Dick Dingley.

Fig 5 Castle Carbery, Co. Kildare, Ireland. Image by Derek Usher.

Fig 6 ‘Castle Carbery,’ watercolour, by artist ‘B.’, 1804. British Library.

‘Her Estuary Would Be Filled Up’

Impulsively, Valeria leaves the party and dashes out into the downpour in search of the long-lost Mr Garrett, waving her lantern wildly at the phantom destroyer floating in the distance. ‘Inconceivably,’ Bowen writes, ‘the destroyer took no notice.’[xxxv] Lost in the forest, she wanders deeper into the realm of fantasy:

Valeria’s mind was made up: she was a princess…When he and she were married (she inclined a little to Mr. Garrett) they would invite all the Navy up the estuary and give them tea. Her estuary would be filled up, like a regatta…She had been excited for some weeks at the idea of marrying Mr. Alban, but now the lovely appearance of the destroyer put him out of her mind.[xxxvi]

Just when Valeria decides that Alban will not do, the rainstorm quenches her lamplight, stranding her in darkness. Buffeted by bats and driving rain, his shoes and ‘soul squelch[ing],’ Alban sets out on a noble quest to rescue her.[xxxvii] He calls out to Valeria and she responds huskily, ‘Mr. Garrett…I’m Miss Cuffe; this is my Castle.’[xxxviii] Mrs Treye and Miss Carbin are breathless at Mr Garrett’s sudden appearance, and Valeria is triumphant: ‘She laughed like a princess, magnificently justified.’[xxxix] Alban stands silently erect, ‘in full manhood,’ ‘as though all three said, “My darling.”’[xl] The story closes with an image of early morning: ‘when next day first lightened the rain, the destroyer steamed out’ of the estuary below ‘the extinguished Castle where Valeria lay with her arms wide.’[xli] This humorously unsubtle post-coital image of the would-be princess Valeria sound asleep, after she is presumably ravished by Mr Alban-Garrett, leaves the reader wondering whether it was all just a dream.

Conclusion

Expounding on the differences between short stories and novels, Bowen contends, ‘The short story revolves around one crisis only—one might call it, almost, a crisis in itself.’[xlii] The compound crisis in ‘Her Table Spread’ is that of an Anglo-Irish house, family, and class ‘on the brink of dissolution.’[xliii] The storyline conspicuously echoes that of another Gothic tale, Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ from his collection Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840).[xliv] Poe’s story is also set at dusk in a secluded, derelict manor during an unnerving storm, and it portrays the disintegration of a once-powerful family’s lineage. The protagonists are the last remaining inheritors and they believe their fate is connected to that of their mansion. Similarly, the bachelorette Valeria is the last desperate hope for her Castle and ancestral line, since her widowed aunt Mrs Treye is likely past childbearing age. The isolated Anglo-Irish women in the tale have become living ghosts in their own home. To use a favourite word of Bowen’s, they are ‘enisled’ – quite cut off from society and from modern life. They fall prey to make-believe, fantasising that the naval destroyer will be full of ‘grateful sailors’ who will besiege the Castle in an ‘amorous’ invasion.[xlv] However, as Bowen cautions, ‘Fantasy is toxic.’[xlvi] Elizabeth told her publisher that ‘she considered the stories in The Cat Jumps all had an “escape from life” theme.’[xlvii] She argues, ‘The short story, as I see it to be, allows for what is crazy about humanity: obstinacies, inordinate heroisms, “immortal longings.” At no time, even in the novel, do I consider realism to be my forte.’[xlviii]

As Bowen puts it, ‘Ghosts exploit the horror latent behind reality.’[xlix] Valeria Cuffe is the author’s own crisis writ large, an apparition ‘glittering vastly’ in her imagination.[l] She is an example of what Roy Foster terms ‘the Bowen grotesque,’ which is Elizabeth’s elaboration on the Anglo-Irish ‘Ascendancy genre.’[li] Foster points to Bowen’s assertion that the Anglo-Irish ‘were the “only children” of Irish history – spoilt, difficult, unable to grow up. It is a striking metaphor, coming from someone who was herself an only child.’[lii] Valeria is the outsized embodiment of Bowen’s growing fears surrounding her childless marriage, her burdensome inheritance, and her declining class. The landscape in ‘Her Table Spread’ has a fraught history of successive invasions which reference Ireland’s contested past, including the Anglo-Irish plantation. Invasion also serves as a sexual metaphor in the tale, whose narrative drifts into erotic fantasy. The story ends with a depiction of ‘the extinguished castle,’ which suggests that Miss Cuffe’s sexual encounter with Mr Alban-Garrett was unproductive. The failed marriage plot is a tacit allusion to Bowen’s family history (she had two relatives named Garrett on the Colley side) and her own unfruitful union.[liii] After all, ‘Alban’ is not very far from ‘Alan’.

Bowen considered ‘Her Table Spread’ to be exemplary of her finest work, and in 1959 she chose it for a volume of selected Stories.[liv] She counted it among ‘those which could be considered the most enduring, the most valid, the most nearly works of art. Those chosen should be those fit to survive—stories on which my reputation, if any, could hope to rest.’[lv] In her preface to this collection she discloses, ‘Each of these [stories] arose out of an intensified, all but spellbound beholding, on my part, of the scene in question.’[lvi] Therefore, Bowen implies that the Castle in ‘Her Table Spread’ originated in an actual scene which she beheld, and which inspired her imagination to take flight. In this case, she explains that it was ‘a shabbily fanciful Irish castle overlooking an estuary.’[lvii] The unidentified Castle in ‘Her Table Spread’ is a ‘fanciful’ conflation of recalled places, both real and imaginary. As she remarks in her unfinished memoir, ‘Am I not manifestly a writer for whom places loom large?’[lviii] A litany of places haunt Elizabeth’s invented Castle: Bowen’s Court, Mount Temple House, and the Bowens’ lost houses in Cos. Cork, Tipperary, Kildare, and Dublin. She feared that she could not afford to maintain Bowen’s Court on her husband’s modest income and her own meagre earnings, and unfortunately this proved to be true. Thirty years after she wrote ‘Her Table Spread,’ Bowen’s Court became another lost house for the author. Following Alan’s death, she was forced to sell her home and she did so rather hastily and unadvisedly to a neighbour, who demolished it in 1960. As Glendinning states, ‘She had a sort of nervous breakdown, abandoning Bowen’s Court with wages and bills unpaid, and then sold it, perching with friends and in hotels.’[lix] After losing Bowen’s Court Elizabeth began to retrace her steps, first moving back to Oxford, then Hythe on the Kentish coast where, as a child, she had lived with her mother for several years during one of her father’s extended periods of mental illness. There she bought a small newly-built brick house named Wayside, which she rechristened ‘Carbery’ after the lost family seat from her matrilineal line, thereby reclaiming her own Castle.

Dr Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado is Visiting Research Fellow in the Institute of Irish Studies at Queen’s University Belfast and co-editor of Female Lines: New Writing by Women from Northern Ireland (Dublin: New Island Books, 2017). Follow her on Twitter @drdawnmiranda.

Would you like to submit a blogpost? Check out our guidelines here or email Dr Deirdre Flynn.

To reference this blogpost see our guide here.

Sherratt-Bado, Dawn Miranda. (2020). ‘“The Extinguished Castle”: Elizabeth Bowen’s Haunted House in “Her Table Spread”’, Irish Women’s Writing Network Blog, 21 September 2020, Available at: https://irishwomenswritingnetwork.com/2020/09/21/the-extinguished-castle-elizabeth-bowens-haunted-house-in-her-table-spread/ [Accessed DATE]

[i] Elizabeth Bowen, The Cat Jumps (London: Gollancz, 1934).

[ii] The story was subsequently reprinted in The Listener in 1934, as well as in The Cat Jumps (1934). It is also included in: Look at All Those Roses (1941); Stories (1959); A Day in the Dark (1965); Victoria Glendinning, ed., Elizabeth Bowen’s Irish Stories (1978); and multiple editions of Bowen’s Collected Stories. Seán O’Faoláin featured ‘Her Table Spread’ in his book The Short Story (1948), later reissued as Short Stories: A Study in Pleasure (1961).

[iii] Henry Charles Cole Bowen died at Bowen’s Court on 29 May 1930.

[iv] Elizabeth Bowen, ‘Afterword,’ Bowen’s Court, 1942 (London: Virago Press, 1984), pp. 448-460; p. 451. Hereafter cited as ‘Afterword.’

[v] Elizabeth’s mother, Florence Isabella Colley Bowen, died at Bowen’s Court when the author was aged thirteen, on 23 September 1912.

[vi] Bowen, ‘Afterword,’ p. 456.

[vii] See Victoria Glendinning, Elizabeth Bowen: A Biography, 1977 (New York: Anchor Books, 2006), pp. 54, 108.

[viii] Elizabeth Bowen, The Death of the Heart, 1938 (New York: Anchor Books, 2000), p. 87.

[ix] Glendinning, Elizabeth Bowen, p. 143.

[x] Bowen, ‘Afterword,’ pp. 454-455.

[xi] Ibid., p. 455.

[xii] Elizabeth Bowen, Bowen’s Court, 1942 (London: Virago Press, 1984), pp. 370, 382.

[xiii] Ibid., p. 36.

[xiv] Hermione Lee, Elizabeth Bowen, 1981 (London: Vintage, 1999), p. 34.

[xv] Glendinning, Elizabeth Bowen, p. 122.

[xvi] All quotations are taken from Elizabeth Bowen, ‘Her Table Spread,’ in Victoria Glendinning, ed., Elizabeth Bowen’s Irish Stories, (Dublin: Poolbeg Press, 1978), pp. 18-27. Bowen, ‘Her Table Spread,’ p. 18.

[xvii] Ibid., p. 21.

[xviii] Ibid., p. 18.

[xix] Ibid., p. 23.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Ibid., p. 18.

[xxii] For more on Anglo-Irish views regarding the Union, see Hermione Lee, ‘Only Children,’ in Elizabeth Bowen, 1981 (London: Vintage, 1999), pp. 14-56.

[xxiii] Bowen, ‘Her Table Spread,’ p. 20.

[xxiv] Ibid., p. 19.

[xxv] Ibid., pp. 19, 21.

[xxvi] Ibid., pp. 18-19.

[xxvii] Ibid., pp. 20, 19.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid., p. 20.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Ibid., p. 23.

[xxxiii] Today the structure of Mount Temple House is owned by the Mount Temple Comprehensive School, a secondary school under the patronage of the Church of Ireland, whose notable alumni include U2 bandmates Bono and The Edge.

[xxxiv] Glendinning, Elizabeth Bowen, p. 18.

[xxxv] Bowen, ‘Her Table Spread,’ p. 24.

[xxxvi] Ibid., p. 23.

[xxxvii] Ibid., p. 25.

[xxxviii] Ibid., p. 26.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Ibid., pp. 26-27.

[xlii] Elizabeth Bowen, ‘Preface,’ Stories (New York, Vintage, 1959), pp. v-x; p. viii. Hereafter cited as ‘Preface.’

[xliii] Heather Ingman, A History of the Irish Short Story (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 143.

[xliv] Edgar Allan Poe, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ 1939, in Complete Tales and Poems (Edison: Castle Books, 2009), pp. 171-184.

[xlv] Bowen, ‘Her Table Spread,’ pp. 23, 19.

[xlvi] Bowen, ‘Afterword,’ p. 455.

[xlvii] Glendinning, Elizabeth Bowen, pp. 114-115.

[xlviii] Bowen, ‘Preface,’ p. x.

[xlix] Elizabeth Bowen, ‘Introduction to The Second Ghost Book,’ in The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural, and Fantastic Literature, No. 9 (Bealtaine 2017), pp. 7-10; p. 8.

[l] Bowen, ‘Her Table Spread,’ p. 21.

[li] R.F. Foster, ‘The Irishness of Elizabeth Bowen,’ in Paddy and Mr Punch: Connections in Irish and English History 1993 (London: Penguin, 1995), pp. 102-122; p. 108.

[lii] Ibid., p. 122.

[liii] See Bowen, Bowen’s Court, p. 382.

[liv] Elizabeth Bowen, Stories (New York, Vintage, 1959).

[lv] Bowen, ‘Preface,’ p. v.

[lvi] Ibid., p. ix.

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Elizabeth Bowen, Pictures and Conversations (New York: Knopf, 1975), p. 34.

[lix] Victoria Glendinning, ‘I am in your keeping,’ The Guardian, 7 Feb. 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/feb/07/elizabeth-bowen-charles-ritchie.